Satriani meets Holdsworth (updated): Difference between revisions

Created page with "THIS IS AN UPDATED VERSION WITH ADDITIONAL MATERIAL NOT FOUND IN THE FIRST VERSION POSTED HERE Joe Satriani Meets Allan Holdsworth (Musician special edition 1993) Joe Satria..." |

No edit summary |

||

| (14 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

'''''Summary''': In the 1993 interview between Joe Satriani and Allan Holdsworth, they discuss their musical influences, techniques, and approaches to playing the guitar. They highlight the importance of developing a unique musical voice and continuously evolving their playing styles. The interview emphasizes the significance of serving the composition and expressing oneself through music rather than adhering to a specific style. They also discuss their passion for music, dedication to constant improvement, and unique approaches to creativity and expression in their playing.'' ''[This summary was written by ChatGPT in 2023 based on the article text below.]'' | |||

Joe Satriani | |||

'''THIS IS AN UPDATED VERSION WITH ADDITIONAL MATERIAL NOT FOUND IN THE FIRST VERSION POSTED HERE. THE SECOND SECTION, CALLED "TECHNICAL DIFFICULTIES" WAS ORIGINALLY PRINTED AS A SEPARATE PIECE.''' | |||

==Joe Satriani Meets Allan Holdsworth (Musician special edition 1993)== | |||

[[File:AH-MUS93-2.jpeg|right|400px]] | |||

Joe Satriani reminds Allan Holdsworth about loving what you play; Holdsworth warns Satriani about the dangers of becoming a legend | Joe Satriani reminds Allan Holdsworth about loving what you play; Holdsworth warns Satriani about the dangers of becoming a legend | ||

| Line 209: | Line 210: | ||

SATRIANI: How many should I drink before following it up with a Japanese beer? Um...I don't know. I think when I first heard your playing, Allan, I had real simple questions, and as I learned how to play more I realized that any questions I would ask would be infuriatingly stupid, and that the coolest thing would be to actually sit down and just talk to you here, or go out and have a beer, and I would learn a lot more about Allan Holdsworth in the music, rather than saying, “Do you use a wound G?" or "What kind of speaker is in that little box?” Because I'd never go put on that particular string or construct a box, you know? But when you're a young player, you're really concerned about at least catching up, so you will go out and buy Allan Holdsworth strings to see if it has any effect: “Please, God, you know, will it?” [laughs] But after you play a while you realize that's not what it's all about. What it's about is, everyone has their own voice, and the life process is realizing you have to learn about yourself to let it out. The more you let out on your instrument, the more enlarged that voice becomes, the more recognizable it is. And almost to hell with that—the more cool and fun the experience is of playing. Because then your universe is exploding when you're onstage. Very different from playing someone else's music, just doing a gig, making money onstage. When you're doing your own thing, with your own voice, and there are guys onstage with you playing, and they're with your universe there—what an experience. Nothing can beat it. | SATRIANI: How many should I drink before following it up with a Japanese beer? Um...I don't know. I think when I first heard your playing, Allan, I had real simple questions, and as I learned how to play more I realized that any questions I would ask would be infuriatingly stupid, and that the coolest thing would be to actually sit down and just talk to you here, or go out and have a beer, and I would learn a lot more about Allan Holdsworth in the music, rather than saying, “Do you use a wound G?" or "What kind of speaker is in that little box?” Because I'd never go put on that particular string or construct a box, you know? But when you're a young player, you're really concerned about at least catching up, so you will go out and buy Allan Holdsworth strings to see if it has any effect: “Please, God, you know, will it?” [laughs] But after you play a while you realize that's not what it's all about. What it's about is, everyone has their own voice, and the life process is realizing you have to learn about yourself to let it out. The more you let out on your instrument, the more enlarged that voice becomes, the more recognizable it is. And almost to hell with that—the more cool and fun the experience is of playing. Because then your universe is exploding when you're onstage. Very different from playing someone else's music, just doing a gig, making money onstage. When you're doing your own thing, with your own voice, and there are guys onstage with you playing, and they're with your universe there—what an experience. Nothing can beat it. | ||

==OOH-ING AND AHH-ING: SATCH AND HOLDSWORTH EXPERIENCE TECHNICAL DIFFICULTIES== | |||

RESNICOFF: One important thing about your playing is that you both emulate the voice: Allan used the breath controller on the SynthAxe to create a contour that wasn't necessarily a guitar or a synthesizer, but just music. And Joe's wah-wah pedal is a voice; you don't hear it as, "Now he's doing his 'White Room'". You hear it as sound unto itself. | |||

SATRIANI: Right, definitely, using it to sort of vocalize, to shape the vowels of the notes, the "words." | |||

HOLDSWORTH: I really hated it when an amplifier would make an "00" sound instead of an "ah." I always liked to be able to move the string a certain way to get it to...you can start the note and then you can make it go to an "ah" sound, more like a reed instrument than an "00." I like an "A" rather than an "0." | |||

SATRIANI: It's true. With some amps that are very good performing amps, maybe a Soldano sometimes, it's so together, so well-built, and when you dial up a certain saturation sound it's always there. A Boogie is like that. But for some songs it's just too good, and you can't get away from that one thing it does. It's like a pickup that's wound too hot: It only gives you one thing, although it's really good at givin' it to you, you know? | |||

HOLDSWORTH: That's why I really dig Boogies, because I've got a few different ones, and they all... like, any amp might be really great, but it'll be one. The thing about Boogies is that one manufacturer makes a lot of different amplifiers that actually have different sounds. I change 'em around and keep using different heads. They all have something, a thread of evidence through them; it's kinda got this Boogie thing, but at the same time they all have a character. | |||

SATRIANI: That Dual Rectifier is a nice head, really nice. | |||

HOLDSWORTH: Yeah, I just got one to try and it's pretty amazing. | |||

SATRIANI: On The Extremist we used this '70s Marshall 100-watt combo, and the thing had a voice like no other. It was clear as a bell: You could have 10 rhythm guitars and it would jump right out. And ultimately you'd call it "thin," as opposed to "thick," like the Dual Rectifier; it didn't have a rumbling low end. Its midrange and high end were so pretty and so perfectly defined—the frequencies complemented each other so well that it just sounded big, it had all this air around it. Even within the course of one song, one melody, you'd find that the verse needs something else: You gotta find another amp that'll go brrmp instead of hhhh. They have a different need, vocally, than the bridge, or the chorus or something like that. I showed up for Not of this Earth without an amp and said, "I just wanna use whatever you got in the closet." My producer John Cuniberti was in control of mikes, and I learned from him. We got into using the AKG CT2A on my amp quite a bit, and just moving it an eighth of an inch, or a couple of centimeters, and I would stand there in the control room and say, "Okay, that sounds pretty good, come on in." [laughs] Sometimes we'd do an entire album through one speaker, just moving the microphone along the grille cloth and drawing little diagrams on it for different songs. Andy Johns' way of operating was to set up a couple of cabinets with speaker wire going into the studio with all the heads, and he put up maybe eight microphones in places where he thinks he's gonna get what he needs: two different Shures in a different place for this and that sound. He'd have his own little controller at the board, and he would just sit there and listen to me play and come up with a blend for every part of every song. He didn't move microphones; he moved combinations of microphones. | |||

HOLDSWORTH: I don't like that approach so much. I've experimented a lot, and certain mikes, I can actually hear the capsule resonance. It might be more tedious, but I prefer the method of using one mike and moving it, just because the phase problems drive me up the wall. It's like taking a graphic and notching something out. Whatever combination of two microphones, they're always gonna add somewhere and subtract somewhere else. If you keep one mike in the same position and move the other, you'll hear it go like eeenkoowaa, you have to keep pushing the phase button to check which is closest. But they're never perfectly in phase. And that can be a good thing: You can use it like a notch filter to pull out certain frequencies or to boost others. | |||

SATRIANI: I do that all the time I'd get a sound we would have to mike and get on tape, and I would be inflexible because the technique would demand a certain amount of gain, or a tiny little scooped-out sound. So we'd say, "Well, everything's great, but every time I play G it goes bcchhh," and he'd put in another mike: you know it's gonna be out-of-phase, so you put it in a way so that when that G comes it doesn't reach the tape because it's been phased out. We've used a problematic situation in our favor. | |||

HOLDSWORTH: And you just find the frequencies you want to get rid of. (chuckles] But it's hard. | |||

SATRIANI: It sure is. Andy has it down. He did the Stones, Led Zeppelin, Van Halen, Free-what an enormous impact he's had. I don't know how he does it, but he records the event. Not all people have the experience or have been put in the position where they need good miking technique. Andy described many important records he had to do where the musicians just didn't sound good, and they would look at him and go, "Well?" He couldn't say, "But you sound horrible..." He would try to say, "If you sound bad, it'll sound bad on tape." When you have to be diplomatic you learn to do things with microphones. I grew up as a guitar player practicing at home and playing onstage-what did I know about mike technique? And the first thing you say is, "I don't sound like that!" And then the engineer sits you down.... [laughs] | |||

A musician learns about playing, and an engineer can go to school or work in studios to learn how to read the dials, but what do you do to gain the technique of creating a musical event? You know, that funny thing that's difficult to describe that makes take one different from take two? | |||

HOLDSWORTH: I wish I knew; that's why I always throw away all my live tapes. [laughter] The worst experience I had was when I first started using distortion, a long time ago. We got the opportunity to go into this studio in Leeds, the town close to where I was born, and the guy in the control room couldn't understand why it had to be loud. I kept saying to him, "It's gotta be this volume for this sound to come out of the amplifier," and he kept saying, "No! You turn it down there, we'll turn it up in here." [laughs] I swear! Now everybody's used to it; they all know about distortion and everything. It's even gone the other way, where they're working on making it easy to record without having to make a lot of noise. | |||

SATRIANI: You know, the first time any guitar player gets to sit down with, or maybe pump a CD through a Fairchild limiter/compressor, they'll start to make connections like, "Wow, that's that sound. That's why it sounds like that." Engineers really should explain to musicians what these things can do, because often the musician hears stuff on record, goes out and gets an amp because they read it in an article or something; they go home, turn it on and it's like, “Ucchh, that's not what's on the record.” And of course, what's on the record is so far removed from what came out of the speakers, it really is; there's a microphone capturing what's coming out, it's going through a cable, through preamps, probably a compressor/limiter so it goes to tape properly, through mastering, and God forbid it's got to get turned into a CD, then of course it's not going to sound like you're standing in front of the amp going braaang. [laughs] | |||

HOLDSWORTH: Yeah, you gotta learn to put it back where it started out, or as close to where you think it started as possible, but that's how musicians learn about using mikes: You remember what you used one day as opposed to another. And some engineers are a real problem, because a lot of engineers that I've worked with have their favorite microphones they want to use on everything and force you to use. So they'll stick a [AKG] 414 in front of the guitar, for example; that's a wonderful microphone, it's just that when I use it, that sound I hear in the control room is not the sound that comes out of the box. And it's difficult, 'cause he's doing his job, and then you get into a war and it just screws up! the whole thing. | |||

SATRIANI: It's true. I've done sessions where I keep my mouth shut because I just can't believe what a massive brick wall I'm up against. And there's nothing you can explain to someone if they don't hear it; you just say, "Okay, I guess my guitar is not gonna be that wonderful liberating experience this time; it's just gonna be a guitar sound.” So if you find those people to work with, they can become your partners in sound design. | |||

HOLDSWORTH: Robert Feist was like that for me, inasmuch as he was the first engineer I'd worked with that was selfless; he actually let me loose on the console, and not too many guys'll let you do that. After a while, of course, when I did that, he understood more what I was looking for, so it was a mutually benefiting thing. Well, perhaps not so much for him as it was for me, but...[laughs] | |||

SATRIANI: Some songs defy good mixing, and other songs can be mixed beautifully three completely different ways, and you still get an interesting song out of it. I've never been able to figure it out. Some songs, no matter what you do, there's something stinky about 'em, or you get another tune where you can leave out certain instruments, whole chunks, and the song still sounds really cool: There's something about the sonic quality of the mix that's exciting or enticing. Boy, that's a whole other ball game, even after you... | |||

HOLDSWORTH: I think that's absolutely true, because sometimes you'll go in and put something up and just kinda barely get it going and it sounds great and you go, "Okay, it's done,” and then there's other things you can do. But usually I've found after mixing and everything, you start juggling with a particular song that you've been having problems with—usually after a while you don't know why. You're still working on it and all of a sudden, for some reason, you don't know what happened, but it sounds okay. Have you ever experienced that one? | |||

SATRIANI: Oh, yeah. And everyone says, "What'd you do?" "I dunno? What'd you do?” [laughs] And you start loading those DAT machines and crossing your fingers, [laughter] before anything goes wrong, you know? | |||

That's really funny. | |||

RESNICOFF: You both like to bypass circuitry, and will mix on different consoles than you record on, if need be. | |||

SATRIANI: I think the history of all my records has been such that there's always some disaster or some ridiculous set of circumstances. | |||

SATRIANI: Oh, yeah. And everyone says, "What'd you do?" "I dunno? What'd you do?” [laughs] And you start loading those DAT machines and crossing your fingers, [laughter] before anything goes wrong, you know? | |||

The last two records, Flying in a Blue Dream and The Extremist, were recorded in so many different places that it was impossible to get 'em all mixed on one board. But yeah, using mike preamps and going directly to the tape recorder, so that if you're in New York for a week recording and then you go to Cleveland for a while and then you're back in L.A. or San Francisco, you're using the same mike preamp and always going into a Studer machine so you don't have to deal with putting on tape the qualities of the different recording consoles in those three or four cities. | |||

Ultimately, if I play something really cool it doesn't even matter about that 10 percent of sonic quality. If it's good stuff, people will generally hear that part of it, if they're receptive to it. I remember that I used to listen to hours and hours of early rock 'n' roll and blues and Charlie Parker recordings done in the bathroom or something; it never crossed my mind that I wouldn't listen to it because it didn't reach some sort of sonic quality level. If I was lucky to get a recording of someone that I liked, I'd listen to it all the time. The sound didn't bother me. So for someone to freak out over the mix not being absolutely perfect or that the guitar tone should have been a little more muted or a little less muted, ultimately you have to say, "Hey, wait a minute-even if we got the tone perfect and the sonics of the record were absolutely wonderful, if they don't like what we're playing, no one will ever listen to it. [laughs]. | |||

Music is performance. You just try to get into it as much as you can, and you try and get as much out of it as you can, 'cause it's part of the same thing. And now, as the equipment improves and the sounds supposedly get better, it all just becomes part of the process of trying to improve it. If you take the two things, the same music, one that sounds good and one that sounds bad, then you'll take the one that sounds good, but ultimately, it is the music. | |||

HOLDSWORTH: But generally, even those old recordings, I think they still were trying really hard, unless we're talking about a bootleg or something. | |||

SATRIANI: It's funny how when you're in the middle of trying to get the best bass tone or something like that, someone'll whisper in your ear, “You know, people have bass and treble controls," [laughs) and it'll kinda remind you about when you were 14, and if only you could go back to your little Walkman or stereo system. And you realize you had the controls all this way and that way, and you'd be putting on records saying, "Oh, this record, man, you gotta go like this," and you put on this other guy's record and “You gotta go like..." | |||

HOLDSWORTH: [laughs] | |||

SATRIANI: And I realize that's what we all do: We totally remaster any record that we buy from the store. We take it home and we go, "Hmmm-gzzzhh," [laughs] and we change it. I know very few people who set their controls straight-up flat and leave it alone; ultimately, it's speakers that already have some sort of weird bias in them, like cars these days, the high end/low end is so hyped, you can forget about the midrange.... | |||

RESNICOFF: Allan, are you still using your speaker box? | |||

HOLDSWORTH: Well, I've used it on everything so far, except when I start this new album, I'm not gonna for the first time because I actually have a room that I can use now. He built an enclosed, soundproofed speaker with built-in microphones, which allows him to record guitar quietly, without amplifiers, and always put a consistent tone on tape... | |||

SATRIANI: Yes. I've seen it. It's the same one? It's been a few years. | |||

HOLDSWORTH: I built a few different size ones. It was the biggest one that I made. The coffin, I used to call it. I didn't have the room to record guitar, we didn't have any soundproofing, and with budgets and everything, I really couldn't afford to keep going to the studio and doing what I wanted to do, so I had to find another way to do it, and it worked really good. I don't think the box is as good as what I can get now, without it, by actually using a room and everything. The only way it worked was at really low volume, and that was a good thing about using a little load box on the amp, because if you drove it too hard, the whole box would resonate, so you had to keep the level really low, and that was the trick in using the coffin. Effects should go on after the sound is made. The way my stuff is set up, you make the sound with the amp you want to use, and then kind of putz with effects after the fact. | |||

SATRIANI: Well, it sounds great on record, so you're doing the right thing, that's for sure. | |||

HOLDSWORTH: It's funny, what you were saying about sound, because you can take guys who use completely different stuff and the sound might be similar. Then you get guys who've got exactly the same stuff and it's completely different. It doesn't come out of the box. People just find what they like, what they want to use, and that's it. | |||

SATRIANI: And it's so touchy. And there's the noise generated from equipment versus what it does to set you free to make the performance happen. Of course, then there's the whole idea of, "Is he the kind of guy that plugs straight into a Marshall or does he depend on his effects?" And it goes right...you know where it peaks? It peaks right up with technique versus feeling: These arguments, I don't know who makes them up. [laughs] | |||

HOLDSWORTH: You know, amps are expensive and everything, and a young guy who's just started goes out and buys an amp 'cause someone else...it might be horrendous. I think a lot of kids worry about that when they see a lot of stuff, especially somebody like me, who has a big train set. But I use things in subtle ways. I'll use four single delay lines to get a chorus when you can just go out and buy one box that does it; I can take four used $100 delay lines and blow any thousand-dollar chorus unit out of the water completely. If another guy had four pieces, he'd be able to get four completely different sounds. I guess people try and get the most from the minimum, but I can't find any new multiprocessor company that can make anything like the sound I want—but, the downside of that is it's four against one rack size, so it ends up being a big box. [laughs] You eventually end up with a lot of stuff, but you're not...I'll always remember one gig we played and this guy came up and asked, “Hey, how come I saw two racks up there and I only heard two sounds all night long?!" I was thinking to myself, “Yeah, but were they okay or not?" | |||

-Matt Resnicoff | |||

<GALLERY> | |||

File:AH-MUS93-11.jpeg | |||

File:AH-MUS93-10.jpeg | |||

File:AH-MUS93-9.jpeg | |||

File:AH-MUS93-8.jpeg | |||

File:AH-MUS93-7.jpeg | |||

File:AH-MUS93-6.jpeg | |||

File:AH-MUS93-5.jpeg | |||

File:AH-MUS93-4.jpeg | |||

File:AH-MUS93-3.jpeg | |||

File:AH-MUS93-2.jpeg | |||

File:AH-MUS93-1.jpeg | |||

</GALLERY> | |||

Latest revision as of 14:08, 28 October 2023

Summary: In the 1993 interview between Joe Satriani and Allan Holdsworth, they discuss their musical influences, techniques, and approaches to playing the guitar. They highlight the importance of developing a unique musical voice and continuously evolving their playing styles. The interview emphasizes the significance of serving the composition and expressing oneself through music rather than adhering to a specific style. They also discuss their passion for music, dedication to constant improvement, and unique approaches to creativity and expression in their playing. [This summary was written by ChatGPT in 2023 based on the article text below.]

THIS IS AN UPDATED VERSION WITH ADDITIONAL MATERIAL NOT FOUND IN THE FIRST VERSION POSTED HERE. THE SECOND SECTION, CALLED "TECHNICAL DIFFICULTIES" WAS ORIGINALLY PRINTED AS A SEPARATE PIECE.

Joe Satriani Meets Allan Holdsworth (Musician special edition 1993)

Joe Satriani reminds Allan Holdsworth about loving what you play; Holdsworth warns Satriani about the dangers of becoming a legend

By Matt Resnicoff

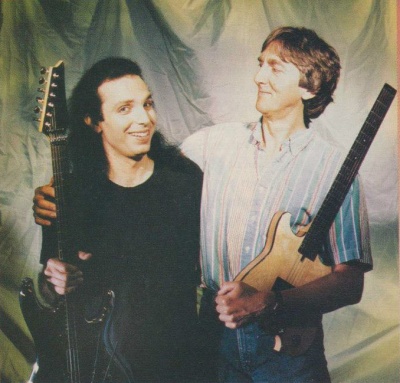

Photos by Ann Summa

Joe Satriani took a hard left turn in the middle of a thought about his latest recording, The Extremist, which entered the pop charts yesterday at #22. “It's interesting you mentioned the song Rubina's Blue Sky Happiness," he said, “because my Allan Holdsworth influence comes through so heavily on that solo, you know? But when we recorded it everyone said, “That's weird; you gotta do it over'—I thought it was the greatest solo I had ever done. It had so much in it, it was so weird, no one could think of putting all that stuff together in a song like that. It was difficult to play over because the song really just wanted some more music. I felt the need inside to, I don't know...express something, and the language that helped me do it was what I learned from jamming with Holdsworth records, his stream-of-consciousness flurries of notes. He opened the door for a lot of things I wanted to play and just didn't know how. I'm glad that survived on the record. And as time goes on and I listen to it, I think, “Man, what would I do if I hadn't heard Allan Holdsworth?'”

In a chorus of self-discovery, many of the world's other most celebrated guitarists—Steve Vai, Edward Van Halen, Yngwie Malmsteen began asking themselves the same question. And those eminently copied players all agree that language alone can't tell the story anyway. Technique was always an incestuous affair among guitarists, but the frenzy heated up once "musicianship" started getting hyped as an acquisition rather than as an instinct. Van Halen is credited with inciting a technical revolution at the end of the '70s with intricate arpeggiated melodies, a two-handed approach he's claimed was catalyzed by hearing lines Allan wove routinely with one. That untouchable fluidity deified Holdsworth among guitarists: The distorted tone attracted rock fans, the exploratory harmony shucked the instrument's clichés and found him favor with the jazz set. His music's got as many labels as a soup cannery, but whatever record bin it lands in, it's the most sophisticated abandon currently available from an electric guitarist anywhere you cannot hear his hands. That said, Holdsworth is as crucial to shaping the evolved edge of contemporary electric playing as any blues or rock legend, alive, dead or otherwise encumbered.

Joe's well-tuned ear-which discerns much of popular metal soloing as "bad Holdsworth"-has always picked up the goods. His remarkable rise to preeminence as guitar icon, instructor, and, in a most unlikely turn, million-selling instrumental artist foreshadowed another major overhaul in the perception of pop guitar. It may have laid the groundwork for pop guitar as a field that no longer needed to be bound to blues-rock, or validated by contrived primitivistic notions of recognizable sounds or ideas—like the human voice. Where Allan shooshed and cried, Joe screamed, growled, fluttered. It's too easy to call Joe the best of the accessible and Allan the best of the inaccessible, and neither would hear it like that anyway. Both insist their language, no matter how evolved, conveys a story about what's in the heart, the voice of the musician. They operate in radically different arenas, with a common intention: to not hear their hands. Joe hadn't seen Allan since visiting him at home years ago, when both were recording for the same label; Joe remembers tripping over Allan's three kids' toys. Since then, both have lost their fathers and have grieved deeply in their playing. On the eve of the release of Allan's Wardenclyffe Tower and of what will be the biggest year in the biggest career of any guitarist since Jeff Beck or Jimi Hendrix, or Allan Holdsworth, the elfin Satriani joined his kindred spirit amid a flurry of hummingbirds at a rooftop table in central Los Angeles.

RESNICOFF: I don't want to slant it so that one guy looks like the elder statesman and one like the newcomer, but facts dictate that when Joe made his first album, Allan's Metal Fatigue was out, he had long been established, and everybody thereafter who plays electric improv couldn't really help but be affected by that.

JOE SATRIANI: Oh, yeah, without a doubt. You know, I should say at the beginning, a big difference between me and Allan is that I built on stuff that Allan pioneered, and in a small way (chuckles] tried to assimilate a lot of what he did on the guitar technically. So it's very different. His musicianship was so far ahead of mine when I was starting out, looking at books and picking out scales and stuff; Allan was in that stage where he was continually reinventing guitar, and I was a fan in the audience, you know what I mean? So I'd have to say in all honesty, I've taken from Allan Holdsworth, and tried to figure out, “How can I use what this guy has done to further what I'm trying to say?" I'm sure he never [laughs] listened to Joe Satriani records in that light....

ALLAN HOLDSWORTH: No, I have, man. But it doesn't sound like that to me. You know, because over a great period of time when people play electric guitar, bit by bit they take something someone did, or move it around and change it, and I didn't get that so much from when I first heard you; I didn't hear anything deliberate.

SATRIANI: Well, good. [laughs] Good! I tried. I always had a thing against the sound of the pick. I always thought it was a deliberate sound. Say it was an instrument in the orchestra, and they had the Al Di Meola section and the Allan Holdsworth section, they'd write differently for each if they wanted the chup-chup-chup for every note or if they wanted the fluid sheets of sound coming out, like Allan plays. And one day I realized I really didn't like that, it isn't part of the music and it's taking up so much sonic space. And I didn't know what to do about it until after a jam session a friend said, “I have a record of a guy who's doing what you're trying to do." It was Tony Williams' Believe It record, and it was the first time I heard you play...

HOLDSWORTH: Ugh. (laughs]

SATRIANI: ...and I couldn't believe it. It was beautiful, and at the same time it made me feel like I wasn't such a nerd for trying to figure out a way of playing that didn't include the sound of a chomping pick for every single note. So it validated a sort of strange idea I was having, that someone was already so far ahead with it.

HOLDSWORTH: Well, I never felt I was ahead with anything. But I look at it compared to other instruments. I never really wanted to play guitar; I wanted to play a horn, and think about how horrendous a horn would sound if you were tonguing every note-it would drive you nuts. There's a time and a place for all of it, and I think guitar's more like that now. There's people mixing a lot more picking and less picking, which is nice. But guitar being a percussive instrument, it was harder to get away from that. Using amplifiers and trying to get a different kind of sound just seemed a fairly natural thing to do. I didn't want the guitar to be percussive like a marimba or something, where the only way you get the note is to hear it begin. And in the beginning, I'd always be able to hear the notes that were picked and the ones that were hammered on, so I started practicing actually playing accents with the hammered notes and making the picked notes seem more silent than the one you played with your left hand. I never got it a hundred percent, but I keep modifying the technique as I go.

SATRIANI: I tried almost anything to get it happening: practicing atonally so that my musical mind wouldn't hold back my physical mind. Because sometimes the musician in me will start saying, "Oh, that's a horrible bunch of notes," and might stop my fingers. So I started getting into playing without listening to the notes at all, just to try to develop the fingers, and I started gluing little teeny weights on the back of my nails of my left hand, little funny things like that; some people take rubber bands and tie 'em up. I'd try anything to get me away from the technique I had been brought up playing, which is pick the notes and listen. And when I finished that segment of practicing, I'd play music and I'd see how that experience had affected my technique. And what happened was, there was a reserve of all this new stuff. There was no bias in my history against it, it was simply new technique waiting to be played; I'd get an idea of a burst of notes and the left hand would go. I worked like that for a while, because I didn't want it to be jaded, you know? A guitarist today winds up listening to players famous for picking a lot, and it colors their opinion of picking. That's not good for a student, because there's a zillion subtleties in that one little movement, and maybe someone will revolutionize the art and have that rapid picking sound with so many volume plays that it'll take it to a new level-and maybe it's a matter of not being exposed to these other players so you're thinking freely. I think about that again because I was in the dark until I heard Allan, and then I saw, "Well, that means there's gotta be a whole world out there of all this amazing technique, and you have to start from scratch and say, 'What are my hands and fingers capable of doing?""

RESNICOFF: Allan wasn't barraged with guitar information growing up; you were innovating in a different era.

HOLDSWORTH: I didn't think of it as an innovation. I was just trying to do something that I wanted to hear. I went through a period of working on the legato style, but at the same time I had this thing in the back of my mind saying, “There's something wrong with this," and I'd drift back into periods of trying to play more legitimately-chuckles or what was classified as legitimate in my head, in terms of right hand/left-hand. And I'd make recordings, like everybody when they start; over a period of years I'd go back and find something I did before when I was noodling with the legato thing, and I thought, "Oh, that sounds okay-maybe I should've persevered with that." And then I went back to it. And then kept going on that. One thing I didn't like about the legato technique, that I've worked on getting out of ever since, is the way it's easy to play notes going in one direction or the other. So what I try to do is limit myself, when practicing, to no more than two notes going in any one direction. It was just to try and-similarly to what you were saying, Joe-break up your way of thinking about it or practicing it. It's not something that just happens on its own; there's a real reason for doing it. As far as I'm concerned, there is only melody, one way or another. I guess one man's meat's another man's poison, so one man's melody is another man's horror story.

RESNICOFF: Another thing both of you do is reshape conventional chord structure. One voicing you both play is the first chord in Joe's "Always," and in "White Line"—that minor second thing

SATRIANI: Major with an added fourth? Yeah, done that way, yeah, sticking them together. There's a lot of ambiguity in a chord like that, but also a certain accessible beauty that comes from rethinking how you can play something so simple.

HOLDSWORTH: Well, because my dad was a jazz musician he had records of most instrumentalists including guitarists, so after Charlie Christian and Django Reinhardt, I grew up listening to Joe Pass and Jimmy Raney; I loved Jimmy Raney. And all those guys are absolutely wonderful, but there was something about the guitar that I didn't like even then. Guitar chords only consist of four different notes, generally-you can play more, but they're usually duplicates or an octave-so it becomes more limited. When I'd hear chord things, I'd recognize the sound of the chords straight away; you almost knew what was coming. You'd appreciate the fact that it was marvelous—it never took anything away from that—but I thought it would be nice to do something where the chords sounded different. And unfortunately, unless you have two guitar players and they don't duplicate notes, the chords will naturally sound a bit more ambiguous in some ways, although they're not, you know? So I started to think of chords as being related to families. I don't hear one voicing move to another; it's like, that chord belongs to a family, a scale, and the next one belongs to a different family, and I try to hear the families change as the sequence goes. You can play anything that sounds nice, as long as the notes are contained in those scales as they move from one to another. I hear that in piano players I like. They don't sound trapped with this chord-symbol thing. Whenever I hear Keith Jarrett, it's just these harmonic/ melodic ideas, and they all sound right, but at the same time have this kind of freedom in the way they move.

SATRIANI: There should be a word for it, or a phrase... maybe if people could use the word "harmony” to describe the end result of a chord progression, and think of the harmony as this fluid family of notes being fed by the chords. So the chords aren't the end they're just the building blocks to the ultimate thing which is the true harmony, and then melodies and solos feed off the end result of the harmony.

HOLDSWORTH: Yeah, it's more fluid, where the harmony moves from one place to another, and each time it goes by you could play completely different chords or notes, but they're correct because they follow the harmonic sequence. But it's not like every time you see a chord you play some other inversion of it—if you say, “Stop! What chord is that?" it might not even constitute an inversion of the chord you wanted, though it'll be harmonically correct, because you'll be playing notes from within that scale. It's like giving all different names to the same scale. See, the only thing that makes one scale different from another is the way they are different intervallically. I don't give a C major scale seven different names, because as long as you know what it sounds like in each mode as you move the bass up from C-I don't think of it as so fixed. It is fixed, but in another way.

SATRIANI: What Allan's saying can also be applied to something really simple. In a Stones song like "Under My Thumb,” you have a couple of guitar players, a few other instruments. It's a simple chord sequence, but they're not really duplicating each other; they're jamming on each chord, and if you wrote it down, you'd listen to one track and say, "Sounds like Richards is doing sometimes a major, sometimes a seventh, sometimes suspending it, and Brian Jones is doing something like it but not quite at the same time, and there's keyboard in there embellishing," not the fact that it's G, but G relative to what? To the feeling of the song at that point; like at the end of the verse when you're sittin' on that G and sometimes this guy's making it dominant and the other guy isn't. They're saying the chord is not the end, it's just a suggestion as to where the harmony is at that moment. So you have the whole family to play with. There's no way to say ahead of time, “Wrong. This note, nobody can play it,” because it depends on the circumstance. Someone, (laughs] a year from now, will figure out a way to throw in a note no one else had success with 10 years earlier.

RESNICOFF: Allan once said something cool: "Style doesn't signify a thing; it's just the way you do something." I asked if style was a consistency in the vernacular you use, and he said, “Yeah, but it's meaningless, like a faceplate from an old amp."

HOLDSWORTH: Well, it is. I was never interested in manufacturing a style. It's good to have a personality, because people hear that in the music in one way or another; it changes as time goes on, as well. There's things I used to do that I don't anymore simply because everybody else does them now. But it wasn't because I invented them, it was just that if I started to hear a lot of it from other places, it made me think, “Jeez, that must've been really shallow; it wasn't a musical enough thing in itself that it would hold water permanently." I don't think of a "style” as being as important as other people do. The music is the most important thing, the result at the end, whenever that is.

SATRIANI: It's hard for a musician to recognize their own style, because what they're working on is music, you know? To the listener, the style is all those personal quirks that make up what surrounds what, let's say, a guitar player's playing. But to the player what matters is what they're coming up with.

HOLDSWORTH: And the quirks get in the way! [laughs]

SATRIANI: Yeah, it's built in. When we finally think we've cleared out the quirks, when we've gotten to the truth in what we wanted to say about solo or melody—we think it's free of obstacles—someone'll say, "That's typical Allan” or “That's typical Joe.” And I have no idea what they mean. If you and I were talking about Allan, we could come up with quite a few things we would agree on, and he would probably look at us and say, "What are you talking about?” Usually the listener will say, “Man, how did you do this?" and you wanna say, “Man, that's nothin'. Why didn't you ask me about that part? Now, that was hard!” [laughter] My tune “New Blues”-not one person ever asked me about the rhythm guitar, but it took me how many years of fooling around with two-handed techniques to come up with a part that would be so rhythm-guitarlike no one would ever say, "Oh, what an amazing part," or maybe the opposite--you know how some two-handed parts are so obviously tapping away like typewriters. But here I finally get to a point where it's so wonderful that I've aced myself right out of people noticing it! [laughs] They always ask me, “How'd you get that scream?" “Scream? I do those all the time! That's no big deal!”

HOLDSWORTH: Yeah, obvious things come up, but the obvious ones are always the ones I want to get rid of. (laughter] You know, in the beginning I'd really, really avoid playing any kind of blues licks. All my life I've tried to avoid 'em. Then I find myself in the last couple of years starting to play 'em-you go, “Well, this is insane!" So it's the same reasoning: If I hear something I keep doing, I don't want to do it anymore. I mean, if I listen to an old album, and then I listen to the last album, I hear a difference, a big difference, but maybe what you're saying is, other people don't.

SATRIANI: Right. But believe it or not, it's remarkably consistent. And when you mentioned blues, I even remember a song you did that on; was it "Karzie Key,” from Velvet Darkness?

HOLDSWORTH: Yeah, I guess so.

SATRIANI: [sings theme] It started out with that bassline, like on Bb or something, moves up to B, then goes to E, and then you start jamming. It's just a great little blues progression, and you totally shred it up. I mean, I listened to that little segment over and over again on that record...

HOLDSWORTH: Oh, I hate that record, man.

SATRIANI: ...and that had more to do with the combination of what people call "crazy technique” and blues style. I thought, “Wow.” That reached out and touched me because it was something I wanted to experience playing. My body had to resonate to that, and that made me feel good, so that's what makes me play in a certain way, and part of it I heard on that particular track. But it still sounds exactly like you—I mean, there's absolutely no other person who could ever play like that. [laughs] I can recognize you in so many circumstances, I could describe your sound and phrases. That's style. But if someone said, “Describe yourself the same way,” I wouldn't have a clue. To me everything is servicing the composition, so if someone says, “That's your style,” I say, "No, that's what I did for that song, that's all.”

RESNICOFF: Did you ever transcribe any Allan?

SATRIANI: I don't think I've ever transcribed anything for myself. I never had to. When I was taking lessons from Lennie Tristano, he had me bring in records every week and I had to scat-sing with the solo, note-for note. I remember writing things down in high school, since I had to pass the New York State of Regents, and though I did a lot of music writing, I never got much from it. What I always got off on the most in music was listening and then internalizing it somehow, and I didn't really put the two together until Lennie started telling me to learn what I liked and sing it, to experience the music in a visceral way. Then it's inside, and the things you like about it will come out in a very natural way. I was going to him for improvising and self-discipline, and his thing was truly improvising-getting rid of all the little knick-knacks of your style, anything you may apply immediately because of who knows-what. Get rid of the neurosis and really have music, technique, and then you can improvise. And once I started singing I said, “That's all I'm ever gonna do. I'm never gonna write any of this down unless it's my music and I have to save it.” So I write my own stuff down, but when I listen to someone's music I sing along with it. We've talked about singing Allan's solo in “Red Alert”? [laughs] I brought that one in! It's impossible to sing, I'll have you know. I think Lennie got a kick out of me going bidilopidido.... [laughs] And after that I just figured there is no other way.

HOLDSWORTH: Oh, it makes perfect sense, because it's not like you're shoutin' all the changes out to the punters, [laughter) so they can get off on giving you marks as to what notes you played over what chord. It's definitely something you just hear. And singing it is perfect. The limitations would be that I guess you'd eventually have to end up singing it in your head because there's no way you'll be able to sing some things.

SATRIANI: Some things are hard and you get around it. But his point was to really grasp the music with your mind and your body, your heart and soul. And that your being will then... I'm getting way too fancy for Lennie, he'd be kicking me in the head if he heard me pontificating like this, but it's like your whole being is getting into the music; you're not looking at a piece of paper and going, “Ah, minor sixth-clever little bastard." 'Cause what's that? I mean, I never heard that when I was a kid. And the joy of when you're playing a record...I remember doing some Wes Montgomery, and you get to the end and you can actually nail it, and sing it right from beginning to end. It's not like you've played it, but you experience it in a way that...it's like seeing a picture of a great work of art or being there in front of it. Or listening to a record, and then finally going to the concert and seeing the people play it—it's like wow, you're actually experiencing some guy's music and suddenly the beauty is revealed and no theory in the world will ever get close to describing how wonderful it is as a whole thing, from the heart.

HOLDSWORTH: It seems he was saying it's the melody that's most important, because that's ultimately what you get from being able to sing a solo back, isn't it? 'Cause you're remembering the notes, or the melody, and perhaps not thinking so much, like you said, about what that note is related to this particular chord.

SATRIANI: Yeah, and you're really getting in the soul of the musician. It seemed like as I learned them, I was getting closer and closer, you know? And it's frightening, especially when you're just starting out, and in a period of six days you take a solo, Wes Montgomery or something, and it's like this thing, a mystery, you don't know what he's doing, and by the end of the week you've nailed it and you'll never forget it. And I remember every solo I ever sang, and I don't know why. It's just part of me now, and sometimes when I'm improvising, I hear... it's like they're my ghost teachers, [laughs] all these guys kinda hanging around me that I've learned from, because I digested their musicality. That, with my own idea of what is tasteful and what is not, sort of guides me. But I loved that part of practicing, I really did. Since I taught a lot, I had to transcribe eight hours a day. The last thing I would want to do when I got home would be to transcribe something. (laughs] The thing that made the difference was the student. A beginner started taking lessons from me, and he had a great set of hands, and he brought in, God, I forget what record of yours, Allan, and said, “Man, this is great, how does he do it?” At the time, he was still memorizing major scales. He was so far away, mentally, from understanding where you were at in terms of the tools you were using, but he had drive, so I showed him a couple of completely atonal hammer-on/pull-off exercises and said, “Go home, put earplugs in, just play absolute nonsense as many hours a day as you can—just make sure you're hammering on and pulling off all over the guitar. Then play these weird chord exercises stretching your fingers." He came back and in seven days the kid was amazing. He said, “I don't know what I'm doing," and he was rrrrarrarara all over the place, [laughs) and I said, "Okay, now, let's go over some of the stuff Allan's using." I'm just scratching at the surface of Allan anyway, but I told him, "Okay, he's doing these chords, and some do go like that, and others are quite conservative-looking but sound big. And when he's doing those solos he's playing lots of notes, big intervals, moving across the board and up and down, changing direction all the time, similar to what I had you playing in the last week.” In a couple of weeks he had it-you know, as much as a student could get something as mindblowing as an Allan Holdsworth piece. But the way I approached it was to take it to where he was at. Because if he wanted to play the solo in “Red Alert” it was like, man, where do you start? How do you condense years and years of musical knowledge and taste and then years and years of technical knowledge? But sometimes a student's physicality can pull their mind along. Other times, you find players—and I always thought I was one of these guys who had great ideas, but the fingers were jokers, and it was a constant struggle.

HOLDSWORTH: That's how I always felt: like I could hear all this stuff and could never get my hands to do any of it. And it never changed. It feels exactly like that now, because no matter where your playing is, your head is always...it's usually quite a way ahead of my hands. For me. The distance always stayed the same. No matter what I ended up playing, what I wanted to play was always that much further away.

SATRIANI: [laughs] Very hard to believe.

HOLDSWORTH: But that's what makes it. It's like if somebody walks into a room and you go, "Oh, that's Joe,” 'cause he looks like that. The person is apparent in the player. I guess no matter how hard you try, you can't get rid of it. I'd love to be able to change my face, but I'm stuck. (Joe laughs] So I guess I'm trying to do the same thing with the guitar.

SATRIANI: Just trying to have more fun with it, you know?

HOLDSWORTH: Oh, did you know that Ollie Halsall died?

SATRIANI: Oh, man. About a month ago, yeah.

HOLDSWORTH: Yep. He was living in Spain or something. At age 43.

SATRIANI: You played with him a long time ago.

HOLDSWORTH: Yeah, he was a fantastic guitar player. When I played with this top 40 band, we'd play upstairs on the weekend and the big bands would play downstairs, and then the rest of the week we'd be downstairs, and usually the band would come up and check out the other band. And I remember these guys sayin', “Hey, you sound like that guy Ollie Halsall,” and I'd never ever seen him before; I didn't even know who he was until we played in Tempest. He played totally legato, but I'd never heard him. But he was an influence on me because he was an extremely creative individual. When I first moved to London, he was the popular guy; everybody was saying, "Hey, check out Ollie.” I don't know what happened-he was there, and he was gone. When I saw him he had an SG and the old Gibson Vibrola, the little spring steel tailpiece they had on SGs after the Sidewinder. They worked. I mean, those days, nothing would stay in tune; it was something everybody put up with. I remember in New York when I started playing with Tony [Williams], I used to go around to all the music stores looking for tremolo bars. Everybody would look at me like I was nuts: “Whaddya want that thing for, man? Whaddaya gonna do with that?” It's crazy how it turns around: now no guitar is made without one, you know? [Joe laughs] But I saw the whammy bar, which I don't use much anymore, as just something that happens in a space of time. It's like when those MXR phasers came out and everybody had one, and even on that Tony Williams record, you can [stamps foot] stomp on that and know right away what year it was made! [laughter]

SATRIANI: The bell-bottom of the guitar world! [laughter]

HOLDSWORTH: Yeah! It's just another toy. And as soon as everything starts to sound the same, you go, "Well, time to look for something else.” There's no end to what can be done. It's just, people always look to what's...I don't think they look inside enough somehow.

SATRIANI: Everybody wants a gig. [laughter] You go through that.

HOLDSWORTH: I mean, it's great to like people and be influenced, but there's a difference between being influenced and trying to play like somebody else. I've actually started to hear Scott Henderson clones! Nothing gets left alone. There was a time when you heard Michael Brecker and it could only have been Brecker—and it still could only be, anyway, because there's always something wrong with the rest of it-but it's that strange thing of so many people trying to sound like him. It's sad...it was like that with Jaco. The most important thing about Jaco was what he was playing. But nobody picked up on that; the first thing they go for was the sound.

SATRIANI: Yeah, get a fretless and a JC-120! [laughs]

HOLDSWORTH: So everybody gets a bass with a bald fingerboard, and tries to play like Jaco, and it's all out of tune, hewin' and a-skewin'-and it's a drag, because the thing that made him stand out was the musicality. People are sometimes so influenced by—so intrigued by something, that's the only thing they see.

SATRIANI: That happens to anyone, including us: They hear a certain amount of technique and think that's what the song was about. I went through-and I still do, probably always will-people commenting on solos. No matter how many signs I flash, no one ever says, “By the way, I noticed you played rhythm guitar on your last five albums." [laughter] And certain sections of the press will never pick up on, “No one's ever done a sus4 to augmented back and forth before and then built a Hungarian-scale melody on top of it.” They may be sensitive to other things, like, "Record's really rockin'” or "Love the sound of the drums” or something. I'm sure when Pastorius started to notice the clones, he thought, “Well, this is funky, man-everyone's pickin' up on the superficial part of me, and no one's really listening to what I'm playing, and it's gone so far that now people are playing like that superficial image.” And by then it's out of control. You hear it now with people trying to play like Steve Vai, and they haven't a clue as to what Steve Vai really is all about. But they've emulated the sound, that strange blend of noise with music, that only Steve has control of, that you can notice right away when someone's going brrrr-drrr. [apes pressing and letting go end of whammy to let it wiggle] I heard a CD of some English guy doing that and I just couldn't believe anyone would spend that much money to make a record, only to sound like somebody else. And it was a perfect cop of, you know, [laughs] one-zillionth of Steve. You know, they're missing the depth. I think in this one case, there's a real disparity between the personality of the person and the character of what you hear. Allan's attitude keeps him from stagnating; not allowing yourself to feel that you've accomplished anything significant keeps you on the path towards something better for yourself.

HOLDSWORTH: Yeah, I don't feel I've accomplished anything, really. I just love music, so all I wanna do is play music. There's other things about music, like music business, that sometimes I hate so much that I go through these periods of just wanting to stop, but even if I did I know I'd always keep playing. It's just that I'm so useless at everything; there's nothing else that I can do, so if I quit, what would I do? I guess I just keep going...not keeping doing the same thing, I don't feel I'm doing that I'd get a job in a bike shop first. [laughter]

RESNICOFF: But you're both very consumed by what you do, and there are all these distractions in your lives. Is it a question of forcing yourself to be creative?

SATRIANI: I look at it in a different way: When nothing is happening, when you're creatively spent and you're sitting around with boring people and it's a boring day, you're wearing boring clothes, what's happening? The big question mark descends—“What are we doing? Let's get up and do something." And the more that happens, the more there is to write about, the more there is that needs to be turned into music. I mean, every time I do something, the experience is something, it's part of life, and the music needs life, and life needs music. For me, nothing is more distracting than sitting down with a guitar and realizing that you're playing like shit, and just saying to yourself, “I am a turd today," you know? To me that's the ultimate distraction.

HOLDSWORTH: Well...that's a constant. For me, anyway.

SATRIANI: [laughs] But it's all energy-fed; there's experience, there's something happening. Eventually, you'll get around to the guitar, and you'll have all this stuff that is life that will have happened, and it'll fuel the creative fire. At least it does for me, when I'm sitting down and I realize I've got nothing to say, it's like you've got to put that guitar away and go make some life.

HOLDSWORTH: You hear all the time people who can play really well; you know the guy's practiced and you know he can play, but at the same time you go, "What is it? What is being spoken?”

SATRIANI: That may not be their desire. I've met people like that who don't want to write songs about loss, they don't want to write songs about anything, they just want to be a musician in a band 'cause it's a cool way to make a living, and it looks like a risky yet exciting way to become really famous. I do know those people, and you can't blame 'em—if that's the way they naturally feel about music.

HOLDSWORTH: No, there's other guys, too, that want it bad. I've known a few musicians that really want it, but unfortunately-being really cold—it can never be. I actually know some players who practice all the time and you can see the work, but it doesn't matter. It's the opposite of somebody like Gary Husband, a drummer I've worked with for a long time. When he takes an instrument that he can't play, or initially couldn't play, like guitar, after six months the guy plays incredible guitar, on a harmonic depth you don't get in that amount of time. I always look for that part of the musician speaking out from inside, rather than the guy that just put a lot of work in. I'd rather have the one than the other. I'm lazy; I know I could be a lot better if I worked harder. I still practice, but I've always been the same: I'll work hard on something, but I just get to a certain point and then go out and have a beer. When I should stay there and work. [laughs] The only thing regimented in my life is riding a bike; that's the only thing that gets an allotted space. The guitar is just whenever I feel like it. And sometimes, when I take time off from the guitar, then when I get back to it, even though my hands won't work properly for a few days, I'll feel I've accumulated something in the time I wasn't working on it. 'Cause sometimes if I practice a lot, I find myself doing the same things. Then I think, "My God, all I did is, I got good at practicing." And it's anti-improvisatory, if that's the right word ...obviously you have to have a certain amount of knowledge about chords and scales, but you don't want it coming out in the same way all the time. Sometimes the more I do something, I'll grind myself into the ground—I'll be doing the old albatross. Time off doesn't stop your mind from working, and your brain controls it all anyway. So they get back to the guitar and feel fresh; my fingers won't be used to doing things in a certain way and they'll have this looser way of improvising that I like. I find I can go out on my bike and be more creative mentally than I can sitting with a guitar. And I learn more about my playing when I'm on the road than I do if I sit at home and practice. Because when you're on the road and you have to do something in front of people and you really screw something up, you go, “My God, I can't let that happen again.” It forces you to do something about it. Whereas sometimes you play at home and go, "Oh, man, I didn't quite get that but I'll get it tomorrow." That's that lazy part. When I get to the gig, the lazy part doesn't work anymore. You gotta do it or not do it. Or you get a custard pie.

RESNICOFF: You never seem happy about what you're playing. I always think, “God, how can he justify what he's doing if he feels so passionate about music, and that passion translates into a desire for something more that's never really sated?"

HOLDSWORTH: Well, that's because I never expect to get there. I mean, I never expect to get there in the same way as I know that every one of us has to die at some point. It's not a bad thing. I mean, it's a drag, but it's real. I don't expect ever to play through a tool, an instrument, exactly what I can hear. Because it is an instrument to do something with; by its very nature it's kind of in the way. Perhaps for other people stuff just flows out all the way through, but for me it has a lot of resistance between what comes out and what starts at the other end.

SATRIANI: Sometimes it's hard to recognize when maybe you've done it. The magic has visited you; you had one of those supreme moments. I don't notice it. Maybe it's the next day, or a year later I'll hear something I've done or find a piece of manuscript and go, “Wow. It was happening then and I didn't even know it,” 'cause you are caught up in the logistics; some stuff is so hard to play that you don't notice that you're nailing it because it takes so much concentration to get through it. Every time I make a record I may go back and listen to other things I've done just to make sure I'm not redoing anything, and I'll come across a song I always thought I botched in some way, harmonically, or the melody was a bit loose in the bridge or some little thing, and I'll see it as perfection and I'll wonder, “How come I didn't notice it then?” But then it becomes a joy to listen to, and it's fuel for the fire. It makes me feel like going back in the studio and doing it some more. And sometimes it's stuff that's squirrely sounding or so rough that you realize that it's perfect in its complete incompleteness, or in its roughness it's actually more truthful than if you had polished it up and punched out the bad notes: Sometimes you listen to the raw part and go, “Whoa, there's something there that transcends the technique, so much so that I didn't even notice it yesterday when I did it.” In the course of an hour you may find that your state of mind has changed drastically, and that maybe it was the beginning of the session where you actually had a handle on the meaning of the melody, although at theend you may have technically had a better handle on the performance of it. [laughs]

HOLDSWORTH: Well, that happens a lot for me, because I'm always trying to do something that I'm hearing, and if it doesn't work out I'm miserable. When we were doing Secrets and I was overdubbing the solos, I'd usually just do two or three, go out, and then come back and listen to 'em. There was a couple that I'd done and I remember I just went in the next day and erased 'em all, and then Jimmy Johnson came down, and I guess he was trying to stop me from pushing the red button because if it was up to me...I'd still be there, pushing red buttons all day long. And then I'd go back and find something and go, “Well, what was that?” And it was something that I did before. I'd go, "I wonder why I erased it”- probably because of the sound or something. I mean, some of 'em were obvious why they were erased, they're just really lame.

SATRIANI: (laughs] Although we want to tell one particular story, we're not experiencing the story as it goes down because we're too intent on the story we want to tell, so we're not actually listening to what the result is. And [producer] John Cuniberti taught me a lot about that, since he was sitting right next to me as I did so many solos, and would say really simple things like, “But Joe, that's what it is. That's what you played." Or, "I like that. You're doing something weird here, it's telling me something." I'd look at him and I'd say, "What could he possibly think about what I'm playing when he doesn't know what I'm trying to say?" Sometimes I'd say, "No, this is supposed to mean peacefulness, and he'd say, "Well, it doesn't sound like peacefulness to me, it sounds like angst," or just the opposite—“It doesn't sound like angst, it sounds like peacefulness.” I've always worked with a coproducer, because I notice that, like, right now, I know what I want to say, but what I'm saying isn't exactly what I want to say, [laughs] so I'm saying three sentences for every one I should say, but ultimately I know you guys are understanding eventually the point I'm trying to make. If this were a recording I'd go back and say, "Can I do that answer one more time again? I think I can do better! [laughs] I can get more to the point."

HOLDSWORTH: I never felt that I played anything perfect. I don't know if I actually could. But the thing is that, you know, sometimes I've listened to something afterwards, especially if I hadn't heard it for a while and I forgot about it, and then I hear it again kinda fresher, then I might actually sort of almost like it.

SATRIANI: [laughs] Do you like it while you're doing it—not when you're playing a phrase and moaning about the one that you just left, but while you're inside the line?

HOLDSWORTH: Oh, sometimes I...it's not really so absolute. It's like I'll be trying to do something that I can live with. I want it to come out with a certain amount of...not freedom, but like everything was so much under control of my brain and my hands that each take would be just like a continuous, different stream of ideas. But they never do; I always find a glitch, or like I've tripped up and fell down the stairs in there somewhere. There's always something wrong with them; I'll start out, even if there's a solo that's not too bad, there's always something wrong with it, I mean, and that's true of everything. There's always something wrong somewhere for me with everything.

RESNICOFF: Joe really let go on his first record, an EP. It was highly experimental, Frithian, real free.

SATRIANI: I wouldn't call it free. There were no drums, bass guitars or synthesizers; everything was generated from a guitar. I actually did kick drum parts and pseudo-cymbal and snare parts, scraping the guitar and hitting the pickup magnets with an allen wrench, detuning the guitar into bass registers. It was just a fun thing. A piece on there, “Goodbye,” was completely inspired by Allan. I was determined not to use any special gear. We used all sixteen tracks for direct-injection guitar with a volume pedal, with a one-inch Tascam, and the hiss is unbelievable on this take, of course, [laughs] because it's just these guitar chords going (imitates volume swells). Funny that we should be talking about it sitting here with you, [laughs] because I was really into it. It was like taking Allan Holdsworth and baroque music and putting it together and seeing what you could come up with.

RESNICOFF: As you attempt to attain what you both might ultimately express, I'd think it would require changing the context, stripping it away, getting away from things like song form, even conventional notions of harmony and structure.

SATRIANI: Or the opposite. Believe me, the opposite. Perfect example—the end of the guitar solo in “Motorcycle Driver.” I was determined, just from a gut feeling, that it should be a rhythm thing; it should not be a flurry of the fastest notes flying across your face, or some godawful scream from hell bending speakers all across the world. What was in my body was this thing that went, de de do do de de no nay, and that's all I wanted, was this rhythm part. And I remember asking Andy [Johns], "You know, I bet people are gonna really crown me for this one, but this is exactly what my head says.” In my mind, going way inside or way outside is the same thing; it's like, once you know the enigmatic mode, what's the big deal? Once you've played it, you know the harmony, maybe you've written it out on paper and you've written a couple of songs with it, what's the difference between that and the major scale? It's like, well, everything's the same, isn't it? It's just a question of, “What do I want to do, and do I get off when I'm experiencing that music?”

HOLDSWORTH: I think each time I do a new album or write some new tunes, I'm trying to come up with something that's a little bit different from what I did before, and just basically let the music out. I'm just looking for something else, or looking to move it forward, or maybe it's the same but it's moving. To me, everything I ever wrote is like one long song that hasn't ended yet. And it just goes through all these phases. That's why I always wanted to do film stuff, because I really like the idea of the form of songs being a lot different than the way it's taken to be normally. And I like the idea of looking at a picture, and as the life moves in the film, that you don't have this head and then have to go back to the head just because everybody else does, just like every pop song has to have a guitar solo that's only four bars long. I really like that idea of the moviescape thing, where it just keeps moving, or changing. I've tried pieces like that. As long as it feels like I'm making some progress with myself or with the music, I just let it go. When we recorded Wardenclyffe Tower—and I've only just mixed it-I got so fed up with it. We recorded the album, I think it was last June, and it's kinda been sitting there; we've done nothing to it. I started to mix it, then I didn't like it, then I stopped, and before I knew it we were out on the road again. Then I went back to another studio, mixed 'em, thought it was going okay, and then at the end I listened again and I went, “Jeez, I don't really like them; they're not what I wanted.” So then we're on the road again. So like, now, I pull up the tape to mix something again, but I'm so fatigued with the music-you know, I've heard it so much that I don't want to mix it again! [laughs]

I can never do anything in a set period of time. So I always try to make it—or I'm gonna make it so in the future, anyway that whenever I've got to mix an album, it's psychologically open-ended. If somebody said, “You've got two weeks to mix this album," I might as well not even try. [laughter] When I asked about stripping away contexts, I didn't mean so much inside versus outside as much as like when a writer or philosopher gets so far along that the language changes. Paragraphs and semicolons don't mean anything anymore. The musical equivalent is free music-giving up everything distracting the player from living this peace.

RESNICOFF: So now that you've been playing so long, do you see structural constituents that you've both been trying for so long to cast off but couldn't, because of what people expect in a piece of music?

HOLDSWORTH: No, I don't pay attention to anything other than the way I feel about it. I don't think about what other people expect or anything. Maybe that's why a lot of it is a big disappointment. [laughs] I mean, I sit around worrying so much about what I'm thinking, I'd go nuts if I sat around worrying about other people.

RESNICOFF: Allan, if you were to take your soloing as an example of your approach to music, it's so unorthodox, so individualized, so deconstructed from what people consider to be “guitar," that I'd think even the form in which you get it when you buy it...why have chord progressions, why have drums? I'm curious why the philosophy about "I don't want to play blues licks" doesn't apply to the way in which you present your music on the whole.

HOLDSWORTH: Well, it does. Through the musicians. That's like saying, “Why do I play the guitar?” So if Gary Husband or Chad Wackerman or Vinnie Colaiuta plays the drums, I'm looking for the personality, the person-you know, the musician. The fact that he plays drums in every band in the world as a drummer means nothing. I know what you're saying: Like, if I want to avoid certain things, then why did I choose a conventional setup? But it's not a conventional setup, because each person chooses the musicians they want to work with, so that in itself means something else. You know, I'm not...I'm still tryin' to make music! I'm not deliberately trying to do something that everybody will hate. [laughter] I do it because it really means a lot to me...even though what I'd really like to do would be to write a load of music, a bunch of tunes and have other people play them, and have somebody else play guitar, or just write music for another band. But actually I don't think that would be possible, because I don't know if anybody else would like anything that I ever wrote, so I have to play it for myself.

SATRIANI: And in a certain way nothing's shocking anymore. If someone's form of expression is chopping a piano apart with an axe, or trying to emulate and then create a new version of the music of Muddy Waters or something, after a while it's like, well, there's nothing that's more conservative or more shocking. Everything is equal. People are just trying to figure out how to express themselves, they're trying to figure out what to do with life, [laughs] the general human condition, so once you come to that moment of inner peace about whammy bar or no whammy bar, should I blow up the amplifier or play music through it, should I fire the drummer or hire a second one?, it's like, they're just non-issues.

HOLDSWORTH: Yeah, and I don't make the categories. I can't sit around and worry about whether they call it rock, or jazz, or whatever; my opinion doesn't matter because I'm not gonna be the one that's judging it. I'm just the guy who painted it on the wall. I go to one record store and it'll be filed as one thing, and if I go to another record store it'll be filed as another. Even if I figured out a way to get some guy from another planet who played an instrument that no one's ever seen before, the only reason anybody would like that is because of the gimmick aspect of it. It wouldn't be because the guy was brilliant, 'cause then you might find out later that everybody else on that planet could play a thousand times better than that guy.

SATRIANI: [laughs] What a thought. And plus, there is something dangerous when you try to be deliberate. There's some ugly stench laying around. You can tell when someone's heavy-handed and they don't mean it; they're trying...it reminds me of artists like Cher: They're so deliberately trying to be famous and hip that it's a joke. I mean, look at Michael Jackson. That's so deliberate it's grotesque. It's gotten to a physical level that when I see the guy I feel so sad: It's like a display of a freak and I'm wondering, well, “What went wrong here? What happened between wanting to dance and make music and this thing?” And to me it's deliberate. I bet his intentions are really good, and that he's trying to make the greatest show on earth or be the greatest entertainer on earth...

HOLDSWORTH: Oh, I'm sure he is.

SATRIANI: But this one spectator is totally horrified. And that's what happens when you're masterminding a deliberate attempt to be outside, because, well, what's the oldest word in the book? It's unnatural, you know? [laughs]

HOLDSWORTH: I've seen guys who are really out-and-out jazz musicians-I'm not going to mention any names, but they go out and do... Oh, why not?!

SATRIANI: Mention the names, he loves it! [laughs]

HOLDSWORTH: ...deliberate pop things, and there's always a huge kink in it. Because four guys who could barely play could do that a lot better. You know, the guys who can really play think they can do the easy stuff but can't, because it's always a matter of how far you're pushing yourself. Those guys who play in a basic rock 'n' roll band may be playing to the absolute 99 percent of their ability, so it's gonna sound better than a guy who can play 50 times better than them playing at two percent. It'll be more real. It'll stand up more. I just think you have to find a way to push yourself as hard as you can, go as far as you can go. Maybe even further, who knows?

RESNICOFF: I wanna start closing up because the sun is going down. What about establishing a genuine voice on your instrument?

HOLDSWORTH: It's easier than people think, actually. I used to go to this little bar to have a few beers, Baxter's, down in Irvine-before they turned it into a disco and everybody I knew stopped going when they had live bands, and it wouldn't matter how good or bad the musicians were...and some of them were good, but you'd hear the guitar player keep doing this little thing and you go, "Oh, that's neat.” So long as you remember that if someone was listening to you, they'd probably be able to hear something really unique. The instincts that man has forgotten since he became "civilized," that same thing happens with music: People just don't realize how close they are. Because everybody has a personality, and that's gotta be in the music. It will be there. It's just that in the trying, some of it gets washed away. But then it's taken to the horrific, like that English guy you were talking about, whoever he is. It's sick when it gets to that level. It's not like he loved and appreciated the musicality and learned and then went and did something that had his thing on it. It's like Billy Cobham and Simon Phillips.

SATRIANI: Yeah.

HOLDSWORTH: Some young guys'll go to a seminar and ask Billy Cobham, “Do you know you sound like Simon Phillips?" and it's completely the other way around: It's Simon Phillips who sounds like Billy Cobham. It's kinda nuts! [laughter] There's no figuring all that stuff out.