Igginbottom: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (14 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

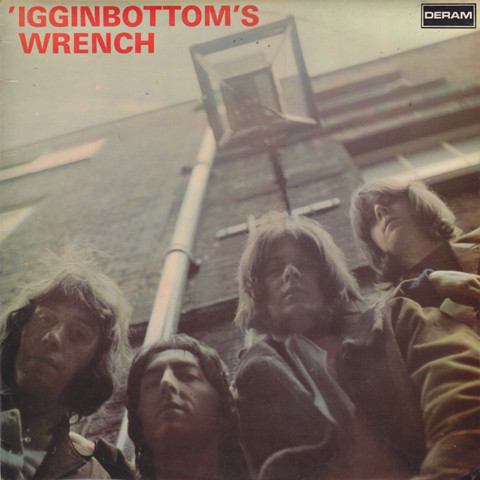

'''Igginbottom''' was a rock group from Bradford. The lineup was: | [[File:IgginbottomCover.jpg|right]]'''Igginbottom''' was a rock group from Bradford. The lineup was: | ||

*Allan Holdsworth: guitar and vocals. | *Allan Holdsworth: guitar and vocals. | ||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

*[[Dave Freeman]]: Drums | *[[Dave Freeman]]: Drums | ||

The band recorded one album, [[ | The band recorded one album, [[Igginbottom%27s_Wrench_(album)|Igginbottom's Wrench]] in 1969. | ||

==[[Allan Holdsworth | =Summary of quotes on Igginbottom= | ||

Allan Holdsworth's involvement with the band Igginbottom marked an early phase in his music career. Igginbottom was a local Yorkshire band, and their 1969 album "Igginbottom's Wrench" was Holdsworth's first commercially released album as a leader. The band's music was a blend of mildly psychedelic and jazzy-pop styles, quite different from Holdsworth's later signature sound. | |||

At the time of recording "Igginbottom's Wrench," Holdsworth had been playing guitar for only a few years and was largely self-taught. Despite his modest assessment of his skills, his distinctive talent as a guitarist was already apparent. The recording process for the album was challenging, as engineers were reluctant to turn up the amplifiers in the studio, making it difficult to achieve the desired distorted guitar sound. | |||

Although the band Igginbottom didn't perform live gigs and primarily focused on rehearsing, they managed to secure a recording contract with Deram Records, thanks in part to their innovative approach to guitar playing and chord voicings, even though their playing abilities were still developing. Despite Holdsworth's mixed feelings about the recording, "Igginbottom's Wrench" remains a noteworthy milestone in his early career, reflecting his early experimentation and musical explorations. | |||

''[This summary was written by ChatGPT in 2023 based on the quotes below.]'' | |||

=Quotes on Igginbottom= | |||

==[[Allan Holdsworth: A biography (Atavachron 1994)]]== | |||

Holdsworth’s early career was frought with desperation and dry spells, and from his late teens through his mid-twenties music was a mostly sporadic venture and hobby; he supported himself primarily repairing bicycles during this time. His first known project as a leader was a low-budget project recorded in 1969 on the Decca label with a few of his local Yorkshire friends-the band’s name was '''Igginbottom''', and the music was derivative of the psychedelic rock fashionable at the time-yet even then, the origins of Holdsworth’s prowess and vision as a guitarist were readily apparent. Veteran British jazz saxophonist Ray Warleigh who travelled frequently around the country, was actually the first professional to "discover" Holdsworth. Warleigh, who played in a large, state-supported dance-hall band (as did some of the other members of '''Igginbottom'''), was instrumental in introducing Allan to the London clubscene. At the time, Holdsworth’s major influences were a wide range of American jazz greats - in particular Benny Goodman’s guitarist Charlie Christian and saxophonist John Coltrane-and in particular the psychedelic, bluesy hard rock of Cream. | Holdsworth’s early career was frought with desperation and dry spells, and from his late teens through his mid-twenties music was a mostly sporadic venture and hobby; he supported himself primarily repairing bicycles during this time. His first known project as a leader was a low-budget project recorded in 1969 on the Decca label with a few of his local Yorkshire friends-the band’s name was '''Igginbottom''', and the music was derivative of the psychedelic rock fashionable at the time-yet even then, the origins of Holdsworth’s prowess and vision as a guitarist were readily apparent. Veteran British jazz saxophonist Ray Warleigh who travelled frequently around the country, was actually the first professional to "discover" Holdsworth. Warleigh, who played in a large, state-supported dance-hall band (as did some of the other members of '''Igginbottom'''), was instrumental in introducing Allan to the London clubscene. At the time, Holdsworth’s major influences were a wide range of American jazz greats - in particular Benny Goodman’s guitarist Charlie Christian and saxophonist John Coltrane-and in particular the psychedelic, bluesy hard rock of Cream. | ||

==[[No Secrets (Facelift 1994)]]== | ==[[No Secrets (Facelift 1994)]]== | ||

Aside from Allan Holdsworth’s little known involvement on Donovan’s hit "Hurdy Gurdy Man”, his first excursion into the recording world was the '''Igginbottom'''’s Wrench album, a 60s jazzy pastiche reminiscent of other early proggers (Colosseum, Giles, Giles and Fripp), with our interviewee supplying vocals as well as guitar. I suggested to Allan that his playing even at this early stage was quite well advanced. | Aside from Allan Holdsworth’s little known involvement on Donovan’s hit "Hurdy Gurdy Man”, his first excursion into the recording world was the '''Igginbottom'''’s Wrench album, a 60s jazzy pastiche reminiscent of other early proggers (Colosseum, Giles, Giles and Fripp), with our interviewee supplying vocals as well as guitar. I suggested to Allan that his playing even at this early stage was quite well advanced. | ||

| Line 23: | Line 34: | ||

"What happened right after the '''Igginbottom''' thing was that I went right back to doing my day job - I was just gigging around with local club bands playing working men’s clubs. There was this bandleader called Glen South - he had a band that worked in one of the Meccas, in Sunderland think it was, and he always liked my guitar playing. He asked me if I’d join that particular thing, that Mecca band. And I thought that that’d be quite good because it was more money than I was actually earning doing the day job. And I thought, ‘I can practice during the day’. So I took the job and I did it for about three years. Two of those years were in Sunderland and then we moved to Manchester to the Ritz. | "What happened right after the '''Igginbottom''' thing was that I went right back to doing my day job - I was just gigging around with local club bands playing working men’s clubs. There was this bandleader called Glen South - he had a band that worked in one of the Meccas, in Sunderland think it was, and he always liked my guitar playing. He asked me if I’d join that particular thing, that Mecca band. And I thought that that’d be quite good because it was more money than I was actually earning doing the day job. And I thought, ‘I can practice during the day’. So I took the job and I did it for about three years. Two of those years were in Sunderland and then we moved to Manchester to the Ritz. | ||

"It was a good band - we were all really great players. In the band at the time we had Dave McRae and Gordon, sometimes even two piano players." Had this then been the first meeting with Gordon Beck, who Holdsworth was to form such a creative relationship with in later years? "No, I actually met Gordon a little before that when I was with '''Igginbottom''', because when we were trying to get that '''Igginbottom''' thing going we played at Ronnie Scott’s." | [On Nucleus:] "It was a good band - we were all really great players. In the band at the time we had Dave McRae and Gordon, sometimes even two piano players." Had this then been the first meeting with Gordon Beck, who Holdsworth was to form such a creative relationship with in later years? "No, I actually met Gordon a little before that when I was with '''Igginbottom''', because when we were trying to get that '''Igginbottom''' thing going we played at Ronnie Scott’s." | ||

==Allan Holdsworth (NPS Radio transcript)== | |||

PH: But musically if I remember in the 60s, you had the beginnings of the Beat-dom [Note: This word is most likely a reference to the emergence of Beat music, British beat, or Merseybeat] and the local bands which were playing the hits of the day rather than your own stuff, and you were with a band called Igginbottom that played - basically you were more into Coltrane than the Beatles or the Stones. | |||

AH: Yeah well that’s true, but I also before that, haha, I still did play with a lot of local bands in that town, Jimmy Judge and the Jurymen, they’re all like funny names, haha, Margie and the Sundowners, all these people, it’s great, I’ll have to ask them what they’re all doing. But that was more like playing in working men’s clubs and just doing the cover tunes, and then Igginbottom was really just an experiment and the unfortunate thing is that it actually got recorded when it never should have been, haha, because it was too soon, too early to be doing any recording really. It didn’t deserve it to be recording then. | |||

PH: It’s quite amazing to think that a band that played experimental stuff would be signed by a Decca label, Deram records wasn’t it? | |||

AH: Yeah, well that came about because of the other guitar player. There were 2 guitar players in the band, Steve Robinson and myself, and what we used to try to do - which was a very good idea, it’s just that we weren’t very good at it… but it was a good idea and we played like polychords, and I’d play 4 notes, and he would play 4 different notes and every chord was usually like an 8-note chord, which was unusual for the guitar, and we’d work on it. Some of the ideas were pretty good, it’s just that we couldn’t play, haha, but, uh, I forget where I was going with ya… | |||

PH: But how did you get a record deal… | |||

AH: Yeah, well, Steve Robinson was friendly with a guy, it was actually the singer in a pop band at the time called A Love Affair, Mick Jackson. Mick Jackson heard us playing and he thought he liked it so he - I don’t know how or why we ever got the opportunity to do this - but he dragged us down to Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club. Ronnie’s had the main club and the upstairs, so we set up upstairs and we played, and all the guys who were working at Ronnie Scott’s, including Ronnie himself when he was still very much alive in those days - we played and then they disappeared, and we thought, ‘uh oh, we’re out of here, this is it’, but when we came downstairs we realized that they actually really liked it, so it was pretty interesting. But unfortunately we were dealing in a time where like, if we were using any type of distorted guitar sound, the recording studios didn’t really know what that was yet. So if I tried to go into the studio and play loud - in other words, it was loud to get the distorted guitar sound - they’d say, ‘No, no, you’re doing that all wrong – YOU turn it down, WE turn it up in the control room’, we’d go, ‘no, that’s not how it works, we play loud, you turn it DOWN in the control room’, and it was a constant struggle, it was just a major disaster. | |||

PH: Was that recorded in London? | |||

AH: Yeah, it was actually recorded at Abbey Road! | |||

(Igginbottom excerpt) | |||

AH: It was really funny…we did a couple of demos, the same band, that turned out really good, because we did one at Matthias Robinson Studio and he was the guy actually who designed the Matt Amps - which became popular or later became known as Orange amps - and he had a recording studio at his house and we played loud - and obviously it was right, but, haha, it should have never have been recorded really. It was - we were not anywhere near ready to have that happen to us. | |||

==[[Patron Saint (Guitar Player 2004)]]== | |||

At what point did you realize that achieving the ideal of horn-like tone would require a different approach than that of the other players who were searching for the same thing? | |||

Actually, I learned that really early on. I think this is going to make a lot of people laugh, but, early in my career in the '60s, I was playing with some local band, and we had an opportunity to go into the studio. I had an AC30 and a Gibson SG, and I used to like to turn up the amp until it was right at that point where it would get real throaty and fat, but without a ton of distortion. So we started playing, and the engineer came in shaking his head saying, "No, no, no. This is all wrong. You turn the amp down, and we turn it up in the control room." And I'm screaming, "No, you don't understand. I want you to record this sound." This would go on for hours, and it would drive me crazy. I couldn't figure out why I liked my sound at gigs, but hated it every time it was recorded. Horrible. | |||

==[[The Man Who Changed Guitar Forever (Guitar Player 2008)]]== | ==[[The Man Who Changed Guitar Forever (Guitar Player 2008)]]== | ||

Latest revision as of 00:57, 9 November 2023

Igginbottom was a rock group from Bradford. The lineup was:

- Allan Holdsworth: guitar and vocals.

- Steve Robinson: guitar

- Mick Skelly: bass

- Dave Freeman: Drums

The band recorded one album, Igginbottom's Wrench in 1969.

Summary of quotes on Igginbottom

Allan Holdsworth's involvement with the band Igginbottom marked an early phase in his music career. Igginbottom was a local Yorkshire band, and their 1969 album "Igginbottom's Wrench" was Holdsworth's first commercially released album as a leader. The band's music was a blend of mildly psychedelic and jazzy-pop styles, quite different from Holdsworth's later signature sound.

At the time of recording "Igginbottom's Wrench," Holdsworth had been playing guitar for only a few years and was largely self-taught. Despite his modest assessment of his skills, his distinctive talent as a guitarist was already apparent. The recording process for the album was challenging, as engineers were reluctant to turn up the amplifiers in the studio, making it difficult to achieve the desired distorted guitar sound.

Although the band Igginbottom didn't perform live gigs and primarily focused on rehearsing, they managed to secure a recording contract with Deram Records, thanks in part to their innovative approach to guitar playing and chord voicings, even though their playing abilities were still developing. Despite Holdsworth's mixed feelings about the recording, "Igginbottom's Wrench" remains a noteworthy milestone in his early career, reflecting his early experimentation and musical explorations.

[This summary was written by ChatGPT in 2023 based on the quotes below.]

Quotes on Igginbottom

Allan Holdsworth: A biography (Atavachron 1994)

Holdsworth’s early career was frought with desperation and dry spells, and from his late teens through his mid-twenties music was a mostly sporadic venture and hobby; he supported himself primarily repairing bicycles during this time. His first known project as a leader was a low-budget project recorded in 1969 on the Decca label with a few of his local Yorkshire friends-the band’s name was Igginbottom, and the music was derivative of the psychedelic rock fashionable at the time-yet even then, the origins of Holdsworth’s prowess and vision as a guitarist were readily apparent. Veteran British jazz saxophonist Ray Warleigh who travelled frequently around the country, was actually the first professional to "discover" Holdsworth. Warleigh, who played in a large, state-supported dance-hall band (as did some of the other members of Igginbottom), was instrumental in introducing Allan to the London clubscene. At the time, Holdsworth’s major influences were a wide range of American jazz greats - in particular Benny Goodman’s guitarist Charlie Christian and saxophonist John Coltrane-and in particular the psychedelic, bluesy hard rock of Cream.

No Secrets (Facelift 1994)

Aside from Allan Holdsworth’s little known involvement on Donovan’s hit "Hurdy Gurdy Man”, his first excursion into the recording world was the Igginbottom’s Wrench album, a 60s jazzy pastiche reminiscent of other early proggers (Colosseum, Giles, Giles and Fripp), with our interviewee supplying vocals as well as guitar. I suggested to Allan that his playing even at this early stage was quite well advanced.

“It doesn’t sound like that to me! I think I’d only been playing about two years, maybe three years when we did that record. At the beginning I was taught by my father, who was a really wonderful piano player. Then started to find out things for myself. Being an incredibly stubborn guy I wanted to be able to figure things out for myself. Because if I can hear it I must be able to figure it out.

"One of the terrible things about that record was that even at the time we were using distortion but - this might sound really stupid, but it’s the truth - we could not find a recording engineer who would let us turn up the amplifiers in the studio. They’d just turn them down in the control room. The guys would come into the studio and say, ‘;no, no, that’s not how it works - we want to get the sound here and you just record it."

"No, it was actually recorded in London somewhere. I can’t remember where - in about 5 minutes - and it was a pretty horrendous experience. And everybody in the band hated it when it was done! It was basically done by this guy Mick Jackson, who used to be in that pop group who had that big hit - jeez, what was it... the song was "Everlasting Love” - he was the bass player but the singer had a really good voice. It was actually a No.1 hit. I think the band were called "Love Affair”. Had Igginbottom been a gigging band, then? "No. All we were doing with that band Igginbottom was rehearsing. We were just trying to get something together. There was Dave Freeman - my friend Dave; Mick Skelly, who now lives in Australia, and Steve Robinson, who lives in South Africa." This presumably cuts out any ideas of a reunion! "Yes, thankfully! I’m actually sorry that it became a record. There are some other tapes around that I have from rehearsals which would be much better memories of it than that record, but that’s life...."

Holdsworth paints a picture of a fairly shambolic set-up. I presumed that this had maybe then been his first sortie into a band set-up. "No, it wasn’t, actually. I played with a lot of local Top 40 bands, club bands, working around in Bradford. Because I never wanted to be a musician, I was just a listener, and I used to just listen to my Dad’s records and spent most of my time as a kid just listening to the music. And I really wanted a saxophone but they were pretty expensive. And then he bought a guitar from my uncle and he left it lying around and I picked up a few things here and there, but had no real interest in it. And then I guess after a couple of years I started to learn a few things. When he saw me taking some interest in it, my dad, he tried to help me, and from that point on started to meet other people who were in bands and they started to ask me to play with them. So that’s how it started. But I never intended to be a professional musician - it wasn’t like a lot of young people when they first start learning an instrument.

"What happened right after the Igginbottom thing was that I went right back to doing my day job - I was just gigging around with local club bands playing working men’s clubs. There was this bandleader called Glen South - he had a band that worked in one of the Meccas, in Sunderland think it was, and he always liked my guitar playing. He asked me if I’d join that particular thing, that Mecca band. And I thought that that’d be quite good because it was more money than I was actually earning doing the day job. And I thought, ‘I can practice during the day’. So I took the job and I did it for about three years. Two of those years were in Sunderland and then we moved to Manchester to the Ritz.

[On Nucleus:] "It was a good band - we were all really great players. In the band at the time we had Dave McRae and Gordon, sometimes even two piano players." Had this then been the first meeting with Gordon Beck, who Holdsworth was to form such a creative relationship with in later years? "No, I actually met Gordon a little before that when I was with Igginbottom, because when we were trying to get that Igginbottom thing going we played at Ronnie Scott’s."

Allan Holdsworth (NPS Radio transcript)

PH: But musically if I remember in the 60s, you had the beginnings of the Beat-dom [Note: This word is most likely a reference to the emergence of Beat music, British beat, or Merseybeat] and the local bands which were playing the hits of the day rather than your own stuff, and you were with a band called Igginbottom that played - basically you were more into Coltrane than the Beatles or the Stones.

AH: Yeah well that’s true, but I also before that, haha, I still did play with a lot of local bands in that town, Jimmy Judge and the Jurymen, they’re all like funny names, haha, Margie and the Sundowners, all these people, it’s great, I’ll have to ask them what they’re all doing. But that was more like playing in working men’s clubs and just doing the cover tunes, and then Igginbottom was really just an experiment and the unfortunate thing is that it actually got recorded when it never should have been, haha, because it was too soon, too early to be doing any recording really. It didn’t deserve it to be recording then.

PH: It’s quite amazing to think that a band that played experimental stuff would be signed by a Decca label, Deram records wasn’t it?

AH: Yeah, well that came about because of the other guitar player. There were 2 guitar players in the band, Steve Robinson and myself, and what we used to try to do - which was a very good idea, it’s just that we weren’t very good at it… but it was a good idea and we played like polychords, and I’d play 4 notes, and he would play 4 different notes and every chord was usually like an 8-note chord, which was unusual for the guitar, and we’d work on it. Some of the ideas were pretty good, it’s just that we couldn’t play, haha, but, uh, I forget where I was going with ya…

PH: But how did you get a record deal…

AH: Yeah, well, Steve Robinson was friendly with a guy, it was actually the singer in a pop band at the time called A Love Affair, Mick Jackson. Mick Jackson heard us playing and he thought he liked it so he - I don’t know how or why we ever got the opportunity to do this - but he dragged us down to Ronnie Scott’s Jazz Club. Ronnie’s had the main club and the upstairs, so we set up upstairs and we played, and all the guys who were working at Ronnie Scott’s, including Ronnie himself when he was still very much alive in those days - we played and then they disappeared, and we thought, ‘uh oh, we’re out of here, this is it’, but when we came downstairs we realized that they actually really liked it, so it was pretty interesting. But unfortunately we were dealing in a time where like, if we were using any type of distorted guitar sound, the recording studios didn’t really know what that was yet. So if I tried to go into the studio and play loud - in other words, it was loud to get the distorted guitar sound - they’d say, ‘No, no, you’re doing that all wrong – YOU turn it down, WE turn it up in the control room’, we’d go, ‘no, that’s not how it works, we play loud, you turn it DOWN in the control room’, and it was a constant struggle, it was just a major disaster.

PH: Was that recorded in London?

AH: Yeah, it was actually recorded at Abbey Road!

(Igginbottom excerpt)

AH: It was really funny…we did a couple of demos, the same band, that turned out really good, because we did one at Matthias Robinson Studio and he was the guy actually who designed the Matt Amps - which became popular or later became known as Orange amps - and he had a recording studio at his house and we played loud - and obviously it was right, but, haha, it should have never have been recorded really. It was - we were not anywhere near ready to have that happen to us.

Patron Saint (Guitar Player 2004)

At what point did you realize that achieving the ideal of horn-like tone would require a different approach than that of the other players who were searching for the same thing?

Actually, I learned that really early on. I think this is going to make a lot of people laugh, but, early in my career in the '60s, I was playing with some local band, and we had an opportunity to go into the studio. I had an AC30 and a Gibson SG, and I used to like to turn up the amp until it was right at that point where it would get real throaty and fat, but without a ton of distortion. So we started playing, and the engineer came in shaking his head saying, "No, no, no. This is all wrong. You turn the amp down, and we turn it up in the control room." And I'm screaming, "No, you don't understand. I want you to record this sound." This would go on for hours, and it would drive me crazy. I couldn't figure out why I liked my sound at gigs, but hated it every time it was recorded. Horrible.

The Man Who Changed Guitar Forever (Guitar Player 2008)

For the benefit of younger readers, and those who could use a refresher, we’ll begin with a recap of the highlights of the guitarist’s illustrious career. Holdsworth’s first commercially released album was 1969’s ’Igginbottom’s Wrench, a mildly psychedelic jazzy-pop outing on which his tones owe more to Joe Pass than Jimi Hendrix. The intriguing chord voicings, dissonant double-tracked arpeggios, rapid note flurries, and remarkable extended solos likely raised more than a few eyebrows.