Chitarre 1987: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

||

| Line 86: | Line 86: | ||

==English version== | ==English version== | ||

''Thanks to Michele for the translation! | ''Thanks to Michele for the translation!'' | ||

'' | |||

Chitarre 1987 | Chitarre 1987 | ||

Revision as of 06:44, 9 July 2024

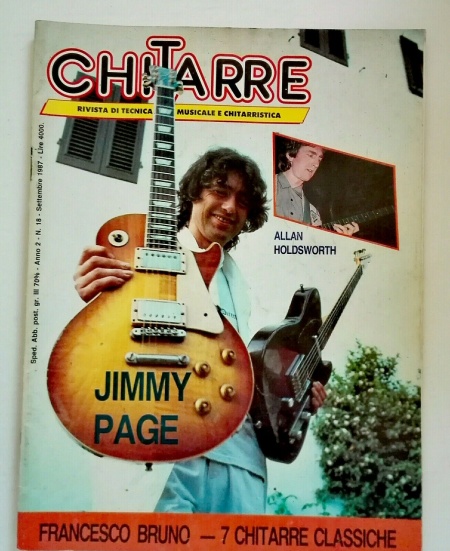

This story was originally published in the Italian guitar magazine Chitarre in September 1987. The introduction to the article was not included in the source material, so the writer of this article is unknown.

English summary

In an interview with Allan Holdsworth, the renowned guitarist discusses his unconventional journey into music, influenced by saxophonists, and how collaborations with various bands shaped his unique style. Holdsworth emphasizes originality, emotional expression, and the pursuit of continuous improvement in his music, reflecting on his distinctive techniques and future aspirations. [This summary was written by ChatGPT in 2023 based on the article text below.]

Original Italian version

Q: Mi pare di capire che il tuo primo approccio alla chitarra sia stato piuttosto inconsueto, ti piaceva il sax?

AH: Certo! Ho preso in mano la mia prima chitarra (molto economica, una decina di scellini...) solo per curiosità; il mio interesse si è sviluppato gradualmente. Ero già ventenne, credo.

Q: Le tue prime influenze, sono prettamente di sassofonisti, allora? Parker, Adderley, Coltrane?

AH: Sì. I chitarristi che ascoltavo più erano Django Reinhardt e soprattutto Charlie Christian, per via del sound. In genere non mi piace il suono della chitarra jazz: è 'gommoso, spento, corto.

Q: Scusa la domanda, ma... hai mai suonato musica 'comune’?

AH: Come no? Ho suonato con i soliti gruppi di musica pop; anche se ascoltavo molto jazz, per via della passione di mio padre, Sam, ottimo pianista; ma non sapevo suonarlo.

Q: Poi sono cominciate le collaborazioni importanti: Soft Machine, Gong, Jean-Luc Ponty, UK; è allora che ti sei addentrato nei meandri di costruzioni musicali piuttosto complesse, strutture armoniche insolite, tempi dispari, no?

AH: Esatto. E questo tipo di esperienza ha naturalmente influenzato il mio fraseggio. Anche la mia musica ha battute dispari qua e là, ma sono saltuarie. Lì si trattava di un tempo dispari fisso.

Q: Non ti sei mai sentito un po... sfruttato come solista?

AH: Non mi ci far pensare! Specie con gruppi come gli UK, il mio compito era di fare assoli; e spesso mi si chiedeva di ripeterli come sul disco, tutti uguali, sera dopo sera... che per uno come me, sempre interessato alla sperimentazione, è una tortura.

Q: Pare che Eddie Van Halen affermi, oltre che tu sei il numero uno nella sua lista, di poter suonare le cose che fai tu, solo se si tira la chitarra un po' più su, verso il torace, quando suona...

AH: [Risatine] Sì, ho letto qualcosa del genere....

Q: [Ridacchiando] Perché sghignazzi?

AH: Guarda, Edward è un grosso talento naturale, innovativo, fa cose incredibili con quella chitarra nel rock. Ma se deve suonare su due accordi... diciamo che non è il suo genere, ecco (ancora risatine)...

Q: La tua musica a volte sembra troppo intellettuale, scientifica. Forse perché stai lavorando su un linguaggio totalmente nuovo, insolito e quindi difficile da recipere. Ho notato anche che non cadi mai sul tiro di tipo ‘nero’, il ‘groove’, per capirci. E una scelta?

AH: La musica per me deve trattare le emozioni, non e una scienza. ma non riesco a sopportare il batterista che si stende sul groove; mi piacciono quelli che suonano, tipo Chad Wackerman… e fantastico, non si ferma neanche se gli spari. E non sgarra mai, anzi, se vada fuoro io devo rincorrerlo perché lui non mi verrà mai dictro. e un sequencer, pronto però a tutta una serie di variazione. E Tony Williams, che mi trascina totalmente quando suona, mi coinvolge, e magico. Il che mi succede anche con musicisti come Keith Jarrett e Michael Brecker.

Q: Quei particolarissimi rivolti che usi... tu dici che dipendono dal fatto che non ti piacciono gli accordi tradizionale più ortodossi. Che cosa ti guida in questa ricerca?

AH: Un ricerca di tipo più pianistico con molto più inventiva. Qui mi serve lo spesso della seconda mano su una tastiera. E poiché non mi piace la pennata, tendo a far suonare tutte le note insieme, usando le dita invece del plettro.

Q: Per rimanere un attimo sulla tecnica oltre ad un vibrato di tipo più classico che rock [parallelo alla corda anziché al tasto] una delle tue caratteristiche più notevoli e la straordinaria facilitata di legato, con un movimento è normale per quello ascendente (hammer on), ma particolare per quello discendente (pull off) vero?

AH: Beh, non mi piace quel miagolio, causato dallo spostamento laterale della corda durante il movimento del dito; così piuttosto che adottare un movimento di strappo laterale alzo e Abbasso le dita direttamente sul tasto.

Q: Veniamo alla parte che farà alzare il sederino dei nostri lettori sui bordi delle sedie: i tuoi assoli. Qual è stata la tua impostazione di partenza per raggiungere sonorità così insolite?

AH: L’originalità, evitando accuratamente di imitare qualcuno.

Q: È per questo che non ti si sente quasi mai su un fraseggio tradizionale tipo rock-blues... Ma non lo usi nemmeno a casa, rilassato sul divano?

AH: No, anche lì preferisco sperimentare.

Q: Sembra che tu ti eserciti e studi molto. Su che fai scale, accordi ed esercizi vari; ma come ti vengono queste diteggiature così strane?

AH: Sperimentando diverse combinazioni di note. Provo a far suonare le note in un certo modo. Faccio cosi: provo a suonare la stessa nota su un corda diversa, ogni volta che compare in una linea melodica; il primo La può essere sulla seconda corda, quella dopo sulla prima, quello successivo ancora sulla seconda.

Q: Ti riferisci alla diteggiature alternative del sax?

AH: Sì, diteggiature false, dove ottieni le stesse note ma con suoni diversi... e quasi come … sembro pazzo... io sono pazzo [risata]. Come ti dicevo, quello di cui ho veramente bisogno e di fermarmi per due anni, ora che so ciò che vorrei conoscere. Voglio dire che forse ognuno sa ciò che vuole conoscere, ma quando devi uscir fuori e suonare, e non hai veramente tempo per lavorare sulle cose che vuoi veramente approfondire.... Tanto sarò sempre scontento [abbassa il tono di voce], sono sicuro che anche dopo questi due ipotetici anni ricomincerò e mi sentirò come prima. Ma suoni cose diverse, puoi essere ad un livello differente e... forse non fa nessuna differenza. Tranne che... la cosa più importante è che suonerei meglio.

Q: Allan, che significa per te suonare ‘meglio? Dov'è il punto in cui sei completamente soddisfatto?

AH: Non c'è. Non lo sarò mai. Se sei soddisfatto, allora quello è il momento di fermarti. Non c'è un momento in cui penso di potermi fermare. Ci sarà un momento in cui i tuoi arti si muoveranno peggio, le tue mani non faranno ciò che tu vuoi che facciano, non ti ricorderai più niente...

Q: Come vedi la situazione chitarristica attuale? Dove va la chitarra?

AH: Non penso mai alla chitarra. So ciò che voglio provare a raggiungere con la mia musica, il prossimo passo, la direzione... il modo in cui la musica ti arriva, come è eseguita. Ho idee molto precise su come tutto ciò potrebbe essere.

Q: Diciamo che ti prendi questi due anni, quale sarà la prossima mossa? Ti chiudi in casa a fare cosa?

AH: Scrivere o... No, solo esercizi. Su tutto ciò in cui sono terribile. Le stesse cose che ho sempre fatto, tranne che invece di essere sul palco a suonare cercando di sopravvivere, mi metterei proprio a lavorare sulle cose che ho bisogno di studiare. Niente composizione, solo studio. Se poi qualcosa uscisse fuori, tanto meglio. Lavoro duro; come dire “sono troppo grasso, devo smettere di bere birra, mettermi a dieta, smettere il biliardo e fare ciclismo". Ecco ciò di cui sento il bisogno, musicalmente; così che possa tornare a dire "ok, mi sento molto meglio ora".

Q: Devi esercitarti sulla tecnica del tapping, così sarai finalmente capace di suonare come Van Halen, giusto? [fine della chiacchierata in quanto questo 'chitarrista che non ride mai' è nel frattempo scivolato sotto il tavolo, ridendo in una maniera tale da non essere più in grado di articolare risposte...]

English version

Thanks to Michele for the translation!

Chitarre 1987

NB! Beware that this interview was done in English, translated to Italian for publication, and now translated back again to English. Allan's quotes are therefore not verbatim.

Q: If I understand correctly, your first approach to the guitar was pretty unusual, did you like saxophone?

AH: That’s for sure! I picked up my first guitar (a very cheap one, about ten shillings…) just out of sheer curiosity. My interested developed gradually. I was already in my twenties, I believe.

Q: Your first influences were mostly saxophone players then? Parker, Adderley, Coltrane?

AH: Yes. The guitarists I used to listen to the most were Django Reinhardt and, above all, Charlie Christian, because of the sound. Generally speaking, I don’t like the sound of a jazz guitar. it’s rubbery, muffled, short.

Q: I apologize for the question in advance but... did you ever play “common” music?

AH: Of course! I played in the usual pop bands. Although, due to the passion of my father Sam who was a great pianist, I was listening to a lot of jazz, even if I couldn’t play it.

Q: Then, you’ve got involved with important collaborations: Soft Machine, Gong, Jean-Luc Ponty, UK. And that’s when you started venturing in a maze of pretty complex musical constructs, unusual harmonic structures and odd time signatures, right?

AH: That’s correct. And that kind of experience had a natural influence on my phrasing. My music has occasional odd beats here and there yet, in that context the odd time signature was a constant.

Q: Did you ever feel a bit… exploited as a soloist?

AH: I don’t even want to think about it! Especially with bands like UK, my job was to play solos and I was often required to play them just like on the record, note by note, night after night… for a person like me, who’s interested in experimenting, that was torture.

Q: It seems that Eddie Van Halen stated that, aside from the fact the you are the number one in his list, the only way for him to play your licks is by rising his guitar high up on the chest…

AH: [Chuckles] Yeah, I read something like that…

Q: [Chuckles] Why are you giggling?

AH: Look, Edward has an exceptional natural talent, he’s innovative and he does incredible things with that guitar of his in a rock context. But if he has to play over a couple of chords… let’s just say that’s not his cup of tea (chuckles some more).

Q: At times, your music may seem too intellectual, scientific. That could be due to the fact that you are working on a completely new and unusual language that, at times, may be hard to recognize. I’ve noticed that you never rely of falling back in the groove. Is that a deliberate choice?

AH: For me, music must deal with emotions, it’s not a science. But I can’t stand a drummer that lays back, spreading over the groove. I like the ones who play like Chad Wackerman… he’s awesome, you must shoot him to make him stop and that may not be enough. And he never messes up, actually, if I miss a beat I have to run after him because he will never follow me. He‘s like a sequencer, but he also has a whole palette of variations ready at hand. And Tony Williams, he completely sweeps me away when he plays, he engages me, he’s magical. That happens with other musicians as well, like Keith Jarrett e Michael Brecker.

Q: About those very unique inversions that you use…You say that they originate from your dislike for more traditional chord voicings. What’s driving your pursuit?

AH: It’s more of a pianistic research, with a lot of inventive. In this case, I resort to using both hands on the fretboard. And since I don’t like strumming, I try to get all the notes to ring at the same time, using my fingers instead of the pick.

Q: Let’s focus a bit longer on technique. Aside from a vibrato that is more ‘classical’ than ‘rock’ (parallel to the string instead of the fret) one of yours most notable characteristics is an extremely smooth legato technique, with a conventional movement when ascending (hammer on), yet a peculiar one when descending (pull off). Would that be true?

AH: Well, I don’t like the meowing caused by the lateral movement of the string so, instead of snatching the string sideways, I try to rise and lower my fingers right on the fret.

Q: Coming up to the part that will keep our readers on the edge of their seats. What was your initial strategy to achieve such unusual sonorities?

AH: Originality, and consciously trying to avoid mimicking someone else.

Q: That must be why we hardly ever hear you using a traditional rock-blues phrasing… But won’t you even use it at home relaxing on the couch?

AH: No. Even in that context I choose to experiment.

Q: It appears that you practice and study a lot. I know you use scales, voicings and various exercises but where do all these unusual fingerings come from?

AH: They are the result of experimenting with different combinations of notes, trying to get the notes to sound in a certain way. I try to play the same note on a different string every time that it appears on a melodic line. The first A can be on the second string, the next one can be on the first string and the following may be on the second string again.

Q: Are you referring to the alternative fingerings on sax?

AH: Yes. Those false fingerings where you get the same notes but with different sounds… I seem crazy… well, I am crazy! [laughing] As I was saying, what I really need is to stop for two years now that I’m aware of what I want to know. I mean, perhaps everybody is aware of what they want to learn but when you have to go out and play, there’s really no time to work on things you want to explore deeply… Yet I know I’ll never be fully satisfied [lowers the tone of his voice], I’m convinced that, after those two hypothetical years, it will start all over again and I will feel the same way as before. But you play different things, you can be on a different level and… maybe there’s no difference at all. Except from the fact that… and that’s the most important thing of all, I would play better.

Q: Allan, what does it mean to you to play better’? At what point are you going to be fully satisfied?

AH: That doesn’t exist. I’ll never be fully satisfied. If you are satisfied, that’s time to stop. There’s never a moment where I think I could stop. But there will be a moment when your joints won’t move as well, your hands won’t do what you want them to do, you won’t remember anything…

Q: What do you think about the current guitar scene? Where is the guitar going?

AH: I never think about guitar. I know what I’m trying to reach with my music, my next step, the direction… the way the music reaches you, how it’s executed. I have a very precise idea about how all of that could look like.

Q: Lat’s say that you take these two years, what would your next move be? Would you lock yourself up in the shed doing what?

AH: Writing or… No, just exercises. On everything I’m terrible at. The same things I’ve always done. With the exception that, instead of being on a stage playing and trying to survive, I would really focus and work on the things I need to study. No composition, just studying. And if something come out of that, so much the better. Hard work, it’s like saying:” I’m too fat, I need to quit drinking beer, get on a diet, quit playing snooker and start cycling”. That’s what I feel like I need now, musically speaking. So that I can come back and say “Alright, I feel much better now”.

Q: Now you need to practice tapping techniques, so you’ll finally be able to play Van Halen, right? [And that’s the end of the chat since, in the meantime, this “guitarist that never laughs” slipped under the table laughing uncontrollably and cannot answer my questions any further]

Chat GPT version

Translated by ChatGPT in September 2023.

Q: It seems that your initial approach to the guitar was rather unusual; did you like the saxophone?

AH: Certainly! I first picked up a guitar (a very cheap one, about ten shillings...) out of curiosity; my interest gradually developed. I was already twenty years old, I believe.

Q: So, were your early influences primarily saxophonists then? Parker, Adderley, Coltrane?

AH: Yes. The guitarists I listened to the most were Django Reinhardt and especially Charlie Christian, mainly because of the sound. Generally, I don't like the sound of jazz guitar; it's "rubbery," muted, short.

Q: Sorry for the question, but... have you ever played "regular" music?

AH: Of course! I played in the usual pop music bands, even though I listened to a lot of jazz due to my father's passion, Sam, an excellent pianist. However, I didn't know how to play jazz.

Q: Then you began important collaborations: Soft Machine, Gong, Jean-Luc Ponty, UK; that's when you delved into rather complex musical constructions, unusual harmonic structures, odd time signatures, right?

AH: Exactly. And that kind of experience naturally influenced my phrasing. My music also has occasional odd time signatures here and there, but they are sporadic. In those projects, it was a fixed odd time signature.

Q: Have you ever felt somewhat exploited as a soloist?

AH: Don't get me started on that! Especially with groups like UK, my role was to play solos, and often I was asked to repeat them just like on the record, all the same, night after night... which for someone like me, always interested in experimentation, is torture.

Q: It seems that Eddie Van Halen claims you're number one on his list and that he can play what you do only if he pulls the guitar up towards his chest a bit when he plays...

AH: [Laughs] Yes, I've read something like that...

Q: [Chuckles] Why are you laughing?

AH: Well, Edward is a huge natural talent, innovative, he does incredible things with that guitar in rock. But if he has to play over two chords... let's say it's not his thing, you know (more laughter)...

Q: Your music sometimes seems too intellectual, scientific. Maybe because you're working on a completely new and unusual language, making it difficult to grasp. I've also noticed that you never really groove in the traditional sense. Is that a deliberate choice?

AH: Music, to me, is about emotions, not science. But I can't stand a drummer who just lays down the groove; I like those who play, like Chad Wackerman... he's fantastic, he doesn't stop even if you shoot at him. And he never misses a beat; in fact, if I mess up, I have to catch up with him because he won't slow down. He's like a sequencer, but ready for all sorts of variations. And Tony Williams, who completely draws me in when he plays, engulfs me, it's magical. The same happens to me with musicians like Keith Jarrett and Michael Brecker.

Q: Those very unique voicings you use... you mentioned that they come from your dislike for more orthodox traditional chords. What guides you in this exploration?

AH: It's a more pianistic kind of search with a lot more inventiveness. Here, I need the thickness of the second hand on a keyboard. And since I don't like picking, I tend to make all the notes sound together, using my fingers instead of a pick.

Q: Staying on the topic of technique, apart from a more classic vibrato, more rock-like [parallel to the string rather than to the fret], one of your most remarkable features is your extraordinary ease with legato, with an ascending movement that's normal (hammer-on), but a particular one for the descending (pull-off), right?

AH: Well, I don't like that "meow" sound caused by the lateral movement of the string during the finger's motion, so instead of adopting a lateral pulling motion, I lift and lower the fingers directly on the fretboard.

Q: Let's get to the part that will make our readers sit on the edge of their seats: your solos. What was your initial approach to achieve such unusual sounds?

AH: Originality, deliberately avoiding imitating anyone.

Q: Is that why you almost never hear you on a traditional rock-blues type of phrasing... But don't you use it even at home, relaxed on the couch?

AH: No, even there, I prefer to experiment.

Q: It seems you practice and study a lot. You work on scales, chords, and various exercises, but how do you come up with these strange fingerings?

AH: By experimenting with different note combinations. I try to make the notes sound in a certain way. Here's what I do: I try to play the same note on a different string every time it appears in a melodic line; the first A could be on the second string, the next one on the first, and the one after on the second again.

Q: Are you referring to alternative saxophone fingerings?

AH: Yes, false fingerings, where you get the same notes but with different sounds... it's almost like... I sound crazy... I am crazy [laughter]. As I was saying, what I really need is to stop for two years, now that I know what I want to know. I mean, maybe everyone knows what they want to know, but when you have to go out and play and don't really have time to work on the things you really want to delve into... I'll still be dissatisfied [lowers voice], I'm sure even after these hypothetical two years, I'll start again and feel like before. But you play different things, you can be at a different level, and... maybe it doesn't make any difference. Except that... the most important thing is that I would play better.

Q: Allan, what does it mean for you to play "better"? Where is the point where you are completely satisfied?

AH: There isn't one. I never will be. If you're satisfied, then that's the time to stop. There's never a moment when I think I can stop. There will be a time when your limbs move worse, your hands won't do what you want them to do, you won't remember anything...

Q: How do you see the current state of guitar playing? Where is the guitar headed?

AH: I never really think about the guitar. I know what I want to try to achieve with my music, the next step, the direction... how the music reaches you, how it's performed. I have very clear ideas about how all this could be.

Q: Let's say you take these two years, what will be the next move? Will you lock yourself at home and do what?

AH: Writing or... No, just exercises. On everything I'm terrible at. The same things I've always done, except instead of being on stage playing and trying to survive, I'd actually work on the things I need to study. No composition, just practice. If something were to come out of it, all the better. Hard work; it's like saying, "I'm too fat, I need to stop drinking beer, go on a diet, quit billiards, and take up cycling." That's what I feel I need, musically, so I can say, "Okay, I feel much better now."

Q: You need to practice tapping technique, so you can finally play like Van Halen, right? [End of the conversation as this 'guitarist who never laughs' has by now slipped under the table, laughing in a way that he can no longer articulate responses...]