A Different kind of Guitar Hero (BAM 1983)

BAM, January 14, 1983 [Interview conducted December 1982]

By Dave Zimmer

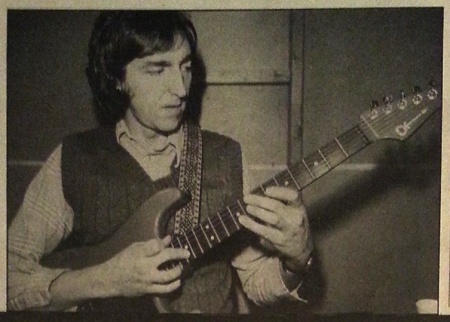

Photo: Tanda Tashifian

Holdsworth as the best in my book. He's fantastic, I love him. -Edward Van Halen

When it comes to putting all the elements together, Allan Holdsworth has got it. I give him more credit than anyone for pure expression in soloing. He has something totally beautiful. -Devadip Carlos Santana

There's a guy named Allan Holdsworth who probably don't get me recognition he deserves, because he's too good. If you play guitar, and ever think you're too good, just listen to that guy. -Neal Schon

Peer praise is no doubt one of the most gratifying strokes a musician can receive. And guitarist Allan Holdsworth, the favorite of just about every pro lead guitarist these days, accepts the compliments with quiet humility. He is far from the stereotypical egocentric electric flashmaster. He prefers to expertly play his instrument rather than simply ravage it.

One is hard pressed to tag Holdsworth's style, because he truly does craft some sounds that have never been plucked out of the electric guitar before. Huge chordal waves reverberate and splash into fluid lead flurries. Melody and dissonance arch together, spiral backwards, then spread out into sometimes eerie, often uplifting cadenzas. Holdsworth never seems to just fly off into excessive jazz-rock fiddling. He takes a listener on journeys that are almost fugal in nature. This is especially true of most of the music on the independently released Allan Holdsworth “I.O.U.”, album. And, it's a sure bet, more enchanting sounds will fill his new album, which he is presently recording for Warner Bros with Edward Van Halen and Ted Templeman producing.

Never comfortable as a hired soloist, Holdsworth nonetheless established a sterling studio reputation in England during the '70s, contributing his shimmering electric fret work to LP's by the likes of Soft Machine, Tony Williams, Gong, Jean-Luc Ponty, U.K. and Bill Bruford. On his own since 1980, Holdsworth, now 34, has been able to fully expand and explore the entire spectrum of his rhythm and lead abilities with a small core of players (first known as False Alarm, then I.O.U.). Because no record company in England would finance an Allan Holdsworth album, the guitarist decided to record one anyway and pay for it himself. Then, when the reception was less than enthusiastic in his homeland, he packed his bags and came to Los Angeles. Here (and elsewhere on the West Coast), Holdsworth quickly attracted a devotional following many of his fiercest fans being fellow pro guitarists.

When I first met with Holdsworth in mid-December at the small Charvel guitar workshop in San Demas, some 40 miles east of LA, he exuded a gentle English manner and seemed genuinely taken aback by all of the publicity that has been channeled his way. He would just as soon stay out of the limelight. In fact, a few days after this interview, he phoned me up and said, "I don't think we talked enough about the other players in the band."

The musicians that Holdsworth is working with now are, indeed, brilliant artists in their own right. Bassist Jeff Berlin, having played previously with Herbie Mann, Gil Evans, Bill Bruford and others, takes the bottom end and pulls it around like soft taffy. Likewise, drummer Chad Wackerman, Frank Zappa's most recent skinsman, is able to bring out subtle nuances, then hammer out forceful rhythms. Singer Paul Williams, veteran of sessions with such fellow Englishmen as Jeff Beck, Jimmy Page and John Mayall, first performed with Holdsworth in a bar band (Tempest) back in '67 [sic]. Together again in I.O.U., Williams and Holdsworth intertwine melodies with harmonic sparkle. Still and all, it is Holdsworth's inimitable guitaring that guides this musical ship. And where it is headed, even Allan himself can't say for sure.

BAM: Why do you think your music is so difficult to label?

AH: I don't know, it's just different, I guess. I wanted to do something I hadn't heard before. That's how I felt It seemed that most of the other things I was hearing sounded so much like all of the other things I'd heard before. I wanted to avoid a traditional jazz approach, because that, even the more modern jazz, still sounds old to me.

BAM: But there must have been some development behind the style you now use.

AH: Well, I didn't originally want to play the guitar. I really liked the saxophone. So I was constantly searching for different sounds on the guitar. I was completely self-taught. I was influenced by my father a lot. He's a really good jazz pianist. And when I was growing up, I didn't realize what I was hearing at the time, but my father played mostly jazz and classical records,

BAM: While you were learning, did you aspire to being a studio guitarist?

AH: No, I was never interested in studio playing. I just wanted to play in a band, which I did for a while. But I got fed up with it really quick and I was basically unemployed for quite a while. Then I met a drummer named John Marshall, he was in Soft Ma chine. We used to play in pubs a lot. He told Soft Machine about me and I started out being a guest in that band and ended up being with them for about a year. Then I got a call from Tony Williams and did some work with him, then Gong, then Jean-Luc Ponty.

BAM: How was it playing with Ponty?

AH: I really enjoyed working with him. I think he enjoyed it too. We'd do lines in harmony. Or, he and I would play in unison and his other guitar player would play the harmony. We really enhanced each other's sound.

BAM: Were you able to interject a lot of your musical personality into most of the sessions you've done?

AH: I tried to make my playing a part of the whole thing. And I would be allowed to do whatever I wanted with my solo section. But I didn't usually affect anything else that much. I was just thought of as somebody to fill up the space.

BAM: When did you first start thinking about recording your own album?

AH: About three-and-a-half years ago, while I was working with Bill Bruford, I really wanted to do it. And UK drove me mad. I was just really, really depressed. There were times I just couldn't stand it.

BAM: Why was that?

AH: Well, I was like an alien in that band. I felt like I came from Mars. Nothing that band stood for meant anything to me. All of the compositions were made up of bits and pieces. The compositions were never thought through from beginning to end, never seen as a whole thing. A lot of English bands are like that.

AH: Also, there was no room for anything to change. It was always the same. It was like playing with tape. Whatever I played couldn't affect whatever else went on. I just played solos. And what was even worse, I didn't even enjoy that part of it. In the end, I just used to get drunk every night. Then I started playing really badly. So I decided I was really doing myself a lot of harm and got out.

BAM: Tell me about the recording of the I.O.U. album.

AH: The album is almost two years old now and was recorded in England at the Barge. L Literally a barge, a little boat, that floats on the water. It's a nice little studio, a 4-track. The room's very small, which tended to make the sound small. When you stick every thing in the middle, it's hard to get an ambiance sometimes.

BAM: When you were recording, how conscious were you about balancing speed and dissonance with a more deliberate melodic style?

AH: I usually don't consciously think about that. But it on this I.O.U. album I wanted to do something that was more musical, that wasn't sort of flash. I suppose I've gone over the top in any direction sometimes. Every body goes crazy once in a while. So I don't think I've ever played so little, in a way. It was really restrained. Because it would be relatively easy for me to just speed along.

BAM: How did you get your rhythm guitar to ring and swell so majestically?

AH: I used volume pedal quite a lot, because I wanted to make the guitar sound like ... well, having no piano or keyboards there, I wanted to make the guitar sound quite wide. And so I would strike the chord and push the volume pedal down so that all of the notes rung at once. Also, I started out using one amp for solos and one amp for chords. But I found I still didn't seem to be getting enough weight behind the chords so l started using two amps for chords, and I thought if I was using two amps, I might as well have a short delay between the two amps. This really made the sound quite fat. So, I think the sound you’re talking about is the use of delay, with a volume pedal.

BAM: What kind of guitar were you recording with?

AH: An old Strat that I had for a long time. Unfortunately, I had to sell it to come to L.A.

BAM: When you replaced your guitar, why did you have a Charvel made instead of getting another Strat?

AH: Because my guitar really wasn’t a true Strat. It was an old Strat body that had Gibson humbucking pickups in it. I’d gouged out a place for them. Fenders are good for experimenting, because they’re modular, easy to take apart.

AH: Just before I came over here, I met Grover Jackson [Charvel guitar maker] in London. I talked to him about specific ideas I had about making guitars. I knew my guitar was really light and it sounded really good. So I thought that there was maybe something to that. Because, for a long time, there was this kind of fashion to make electric guitars really heavy, the thought being, the heavier they got, the more sustain they’d have, which I never believed.

AH: Guitars don't need to be heavy at all. They generally sound better when they’re lighter. And what Grover did was make me exactly what I asked for in terms of neck dimension and kinds of wood. He made four guitars for me out of different woods and my favorite is the basil one. It's almost as light as balsa wood. It's real springy and has a lively kind of tone. It's not hard at all. It almost has a real resonance, like an acoustic guitar, the guitar actually vibrates as opposed to being like a rock.

BAM: How was the Charvel neck dimension different?

AH: Well, on normal Fender guitars, the necks are narrower at the top of the neck than they are on the Gibson. Yet the string spacing is wider on the Fender, which never made any sense to me. So what Grover did was make the necks the same width as the Gibson and set the strings slightly closer together. So there's about an 1/8" gap on the side of each E string. When I used to move the strings on my Fender, for vibrato, I used to pull them off the edge of the fingerboard. It was very easy to do that and it would drive me nuts. That's why I wanted the necks made special.

BAM: Why do you use Hartley Thompson amps exclusively?

AH: Because they're 30 years ahead of everything else, they don't really have much competition. But l do use other amps sometimes, like the new Fender Super Champ, which is a great little amp, and I've got a Yamaha power amp, as well. But the Hartley Thompson can do things that no other amplifier has ever done. It's like having two separate amplifiers in one. Each channel has a separate EQ, and one is super super clean, while the other gets that real sustained kind of sound. And the amp is made with transistors, it's not a tube amp, but I prefer this sound to any tube amp I’ve ever heard. I can get great lead sound and play chords cleaner and twice as loud as lever have before.

BAM: How did you meet Edward Van Halen?

AH: I first met Edward while I was working in U.K. We were the support band to Van Halen on a couple of gigs. Then he said a lot of nice things about me in magazines, which is really nice. Then he came and played with me at the Roxy.

BAM: Where do your two styles meet?

AH: I think of Edward as being a real innovator – because of the way he plays the guitar, not in the way of the context of the music so much. What he’s doing with the guitar is definitely different from what was happening before. So, he did something different. I guess that’s a similarity.

BAM: Why did you and Edward decode to work together?

AH: I guess it started when he brought Ted Templeman to see the band at the Roxy. It’s something that probably wouldn’t have happened had we just done it on our own – if we’d just said “well, let’s play at such a gig and come along”. But I suppose Ted listened to Edward and decided to check it out, and I think he liked it. At least I think he saw some potential there, because he offered us a deal with Warner Brothers.

BAM: How do you feel about working with Edward and Ted Templeman as producers?

AH: All right. I think they [Warner Bros.] are hoping that they’ll make sure we don’t go over the top in the wrong way, suppose. Some outside ears, basically. So, I hope we'll still be friends at the end.

BAM: Are you planning to record the new album with the IOU band?

AH: We'll use Chad (Wackerman, drums) and Jeff Berlin, bass, and Paul Williams, vocals, and I might add another guy. Before, one of the things that was really frustrating to me about playing with keyboard players was not being able to show the other side of my playing - the chordal, rhythm side. But now I've opened that up more and don't need to show it as much. So, yeah, we might bring in a keyboard player. It's hard, in a way, to write for a trio. You always have to imagine the chord sequence - it has to have quite a strong structure. But with a lot of the compositions I'm writing now, I really need that extra part in there, because I can't do two things simultaneously.

BAM: What about some of the electronic innovations?

AH: I really try and stay away from synthesizers, guitar synthesizers, in particular, because when you take away the original personality of the instrument, you get a situation where you can't tell what's being played, is it a guitar or is it a keyboard? Then you have to listen for certain clichés that might be relevant to one instrument or the other. So, I've steered clear of that. There is a new Hartley Thompson hexaphonic amplifier, though, that nobody's come up with a pick-up for yet. It has separate EQ for each string and allows you to use different effects on each string! So, you can have sounds coming out in stereo or use six different sounds. I'd love to use that on a record

BAM: What would you say is motivating you right now? What keeps your playing fresh?

AH: Basically, my own dissatisfaction with my work, because I hate, basically, everything I've done. I can only actually listen to the last two things I’ve done, the IOU album and One Of Kind (with Bill Bruford). And I cringe when I hear them. This dissatisfaction keeps me looking for something else. I'm constantly trying to get better.