A Different View (Modern Drummer 1996)

Summary: Allan Holdsworth, a renowned 20th-century guitar virtuoso, had the opportunity to collaborate with exceptional drummers throughout his career. His journey began with drummer Jon Hiseman in Tempest, followed by John Marshall in Soft Machine, and Tony Williams in New Lifetime. Holdsworth's diverse projects also included work with Bill Bruford in U.K., his own trio with Gary Husband on drums, and solo projects with various drummers like Chad Wackerman and Vinnie Colaiuta. Each drummer brought unique qualities, with Holdsworth valuing their creativity and organic musical connection. His latest album, featuring Kirk Covington on drums, showcases classic jazz standards. [This summary was written by ChatGPT in 2023 based on the article text below.]

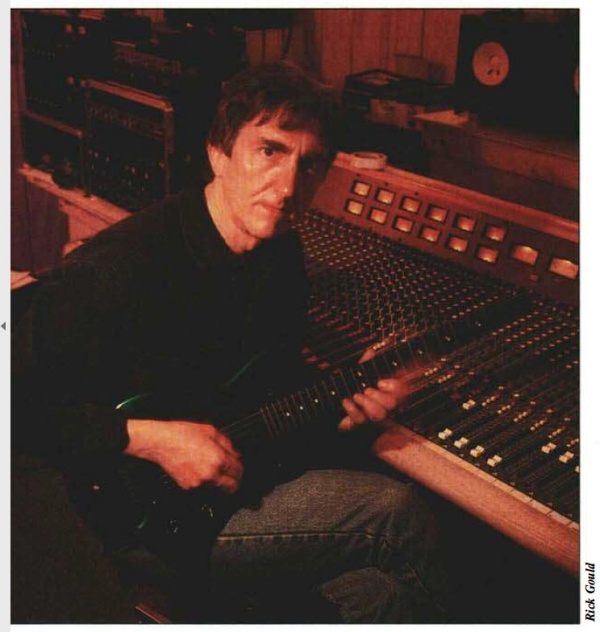

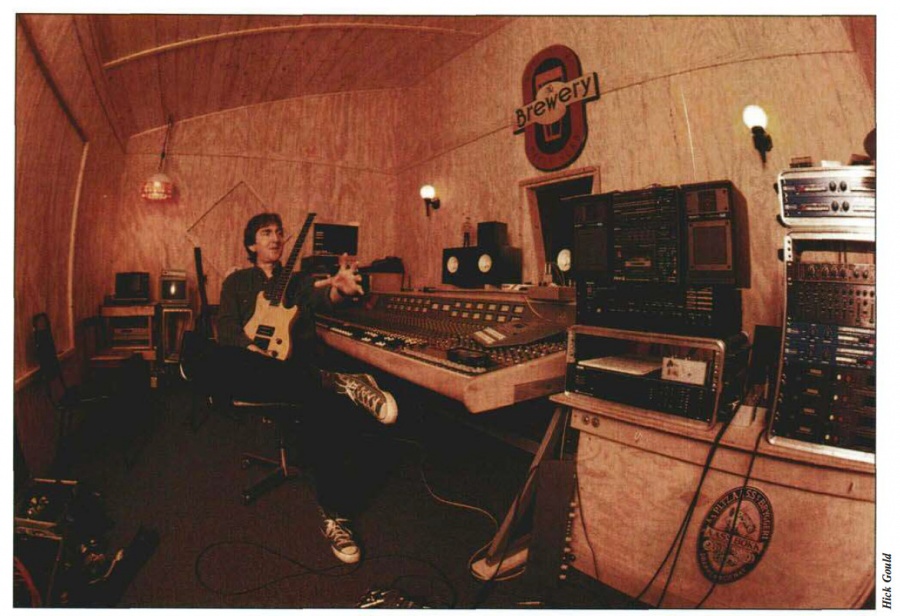

A Different View

Modern Drummer August 1996

By Robyn Flans

Allan Holdsworth is widely regarded as one of the twentieth century's great guitar virtuosos. Needless to say, that has afforded him the opportunity to work with some of our finest drummers. Born in Bradford, Yorkshire in Northern England in 1946, Holdsworth's first break came in the early '70s, when he teamed with drummer Jon Hiseman in Tempest. By 1975 he was working with John Marshall in Soft Machine. In that same year Holdsworth's growing reputation attracted the attention of Tony Williams, who invited Allan to join his New Lifetime. After working with Bill Bruford in U.K. and in Bill's solo band, Holdsworth decided to form his own trio with Gary Husband on drums. Since then he has done solo projects with such drummers as Chad Wackerman and Vinnie Colaiuta, and most recently with Kirk Covington (on Allan's current Japanese release, None Too Soon, whose U.S. distribution is pending).

RF: Who was the first notable drummer with whom you worked?

AH: There were actually two drummers I played with in London who were really influential to me as a musician. One was Jon Hiseman, with whom I played in Tempest in the early '70s. Jon was an absolutely brilliant drummer, especially at that time. He didn't sound like anybody I had ever heard. When I go back to listen to that album, everything sounds good to me except the guitar. The vocals are amazing and the drums are great. That was my first experience of working with someone of that caliber. I came from playing in a Top-40 band with local guys. Then to get a chance to play with somebody like that! The other thing that knocked me out about Jon's playing was that his power just grabbed hold of you. When you played with him, it was like he put his hands on your shoulders and just held you. It was a pretty amazing experience for a guy just arriving in London.

Right after that, Jon wanted the band to stay like a Cream kind of thing, while I felt that the band had a lot more potential, so we split. That's when I joined Soft Machine. John Marshall was the drummer. He was the jazz guy in London around that time. That was a great experience for me. When I look back on my past, I think playing in that band was some of the most fun I ever had in my life. They were great guys and great musicians. I was learning all the time.

RF: You became very well known during the time period when you played with Tony Williams' Lifetime and then with Bill Bruford-first in U.K. and then in Bill's own band. They are such different drummers. What are your thoughts on that?

AH: In the live situation I did with Tony, it was really great. It was about exactly what was going on, like it is with most of the people I've played with since. They've all had that thing where things change, things are moving, it's organic, it's alive. With U.K., on the other hand, I could have stood on my head or set the building on fire and it wouldn't have changed anything that anybody played. It used to drive me crazy. I enjoyed playing with Bill's band afterwards-especially on his second album, One Of A Kind. It was done more as a band than the first one, Feels Good To Me, which was more overdubbed. Bill played with a very compositional approach to the music, which is understandable since he wrote the music. I don't know how he did what he did sometimes going in there and playing on his own with nothing else going on. It's pretty amazing. Obviously, you have to have a vision. He knew exactly what he wanted to hear, and that was the really cool part about it. But I began to feel that I needed to do my own thing

RF: Through your solo years you've used a variety of different drummers for their individual nuances. Can you expound on some of the choices you've made?

AH: I've always felt that the drummer makes the band—and I like to play with people who I feel will enjoy working with me. Obviously I look for people who are gifted musicians. When I started my own band, I started working with Gary Husband. I'd heard about him when I first moved to London. People were saying, "There's this nineteen-year-old guy who is monstrous." Gary's a phenomenal drummer-and a great keyboard player, too. We really hit it off and I've always liked working with him.

RF: What does he bring to your music?

AH: He plays different from anybody else I've ever played with. Actually, most of the guys I've played with have something that makes them unique, which is what I like. I don't like to play with drummers who play like somebody else. A lot of guys make that mistake. They'll think, "He plays with Gary Husband, so when Gary is not around he'll look for someone like that." But I don't. I just look for some other drummer with a musical personality that is distinctly theirs.

If I had stayed in England, I would most likely have ended up playing with Gary all the time. When you have a musical partner—someone who is able to hear what you hear and understand things with out having to speak about them—why look for someone else? Everything I tried to do on guitar, Gary instinctively understood. It was very organic to work with him. I only started working with other drummers in my own band after I made a decision to move to the States, which was around 1981.

RF: And among those was Chad Wackerman.

AH: Right. I met Frank Zappa, and he knew I was looking for a drummer. He said, "You should try the drummer who is working with me; he's really good." I'd been holding auditions without the band there. I just played with each of the drummers who came along. Sometimes you get a guy who spends a lot of time learning the music—but that doesn't mean that he can play. Anybody can sit down and learn it, but I'm not interested in that. When I held auditions, we didn't play any tunes at all; we just jammed. When Chad came along I immediately really liked what happened.

RF: What was it you liked?

AH: It was organic again. There was a connection. To me, half of music is hard work and the other half is some kind of magic. I felt that when I did things, Chad was there—he heard everything. When we did eventually start playing the music together, I knew his interpretation of the tunes would obviously be different from Gary's. But I also knew they would come out sounding good. I try to give the players I work with the freedom to be themselves. That's something I learned when I was playing with Tony Williams. A lot of the time, he wouldn't give me any direction. After a while I realized that was really good for me; I had to contribute something without being told what to do. I always like to do that with the guys I work with now.

RF: Do tracks come to mind that might have been particularly influenced by a drummer?

AH: Everything those guys do influences me. Seventy-five percent of what I play is a response to what someone else is playing. And because of the way the music is presented in the first place, it's not that different with each guy. Of course what comes out is somewhat different with each person, but the result is usually ninety-nine percent what I expected it to be. But sometimes the track turns out so good I go, "Whoa." Gary was particularly good at that. For certain songs he would come up with unique drum patterns that I didn't dictate to him—like when I wrote the tune "Non Brewed Condiment" for Atavachron. The beat Gary came up with on that one is really a great thing. He did the same thing with the title track of that album. He always used to say to me, "Man, I'm afraid of the day when you get me to play on something where I won't be able to think of a new thing." So far he hasn't had that problem.

RF: How about if we play drummer association—I'll say the name of the drummer and then you tell me what immediately comes to mind about him. If I say Tony Williams, what comes to mind?

AH: I remember a lot about the first time I was in New York City. That comes to mind first, and the pleasure of getting the chance to play with someone like that. Musically, I had never heard anybody play like that before—and I've never heard anybody play like that since.

RF: Bill Bruford.

AH: There's a certain pattern Bill plays quite often on the cymbal, so when someone brings up his name, that's what I think of.

RF: Narada Michael Walden.

AH: Whoa. That's a pretty interesting story. I heard Michael play on the Mahavishnu album after Billy Cobham. Everyone thought, "Billy Cobham was absolutely unbelievable, how's anybody going to follow that?" Then the new McLaughlin album came out and there was this insane drummer on it. Geez, where did he come from? The strangest thing was one time I was on a tube train in London, and this guy got on the train and sat exactly opposite me. I looked at him and he looked at me. I had never met Michael Walden and didn't know what he looked like, but I just knew that was him. A couple of days later I went to a concert that John McLaughlin was playing, and sure enough, it was Michael. He's a lovely guy, and a ferocious drummer as well.

RF: What did you work on with him?

AH: Unfortunately I worked with him on a really terrible, doomed album called Velvet Darkness. The problems were no fault of anybody in the band. I was working with Tony Williams at the time, and I got offered a deal to do a solo album for CTI. I think they were used to recording straight-ahead jazz guys who just went in, called out the tunes, and played them. We didn't do that. We were trying to play original material that we hadn't really rehearsed, so we were piecing it together in the studio. They were rolling the tape all the time while we were just running through things, so none of the stuff was really done to anybody's satisfaction. The sad part was that it was a dream band-Alan Pasqua on keyboards, Alphonso Johnson on bass, and Michael Walden on drums—and if we had actually done it the way it was supposed to be done, it would have been great. Unfortunately, it was a total disaster. There are tracks without endings because we had never figured any out. They just stop. It's a mess.

RF: What comes to mind when I say Gary Husband?

AH: A lot of fun. The guy is like a natural-born comedian, and his playing is absolutely beautiful. As far as the closeness to the way things are heard in my head, he is the closest. Sometimes it's like we're one guy. When I play with him, I get lost in it. This is a difficult thing to talk about because I'm not really comparing anybody. You could never do that; all these guys are absolutely unbelievable.

RF: What comes to mind when I say Chad Wackerman?

AH: Precision engineering. Highly polished, detailed, and clear. It's just great, the combination of his ability to fly around with chops, combined with not just going potty all the time. I've been a lucky guy.

RF: How about Vinnie Colaiuta?

AH: He's like Gary in that he's always great for a laugh. I just look at the guy and I have to crack up. Vinnie played on all but one track on my Secrets album, and we also played live together in 1988. As far as drumming goes, he's absolutely insane. He's probably the greatest drummer alive. There's nothing you can say. I definitely want to play with Vinnie again.

RF: Who is on the album you just did?

AH: About a year ago, I was asked to do a track on a Mike Mainieri album, which was a collection of different guitar players doing Beatles songs. It was pretty much last-minute, so he said, "Just pick a Beatles tune, record it, and send it." I called Gordon Beck, a fantastic piano player who was in from England, and he said he had a cool arrangement of "Michelle." I knew the tune was going to be in a straight-ahead vein, and there's only one bass player who comes to my mind when I think of that: Gary Willis. I know how it is with drummers and bass players, so I asked him who he wanted to play with. He said Kirk Covington, which was fine with me. We did the track and I sent it off. They liked it and it came out. I enjoyed working with those guys, so I decided to do an album that was slightly different than my normal projects. I hadn't written any new music, so it was perfect timing. There's only one original on the album, but the rest of them are jazz standards—a John Coltrane tune, a couple of Joe Henderson tunes, familiar tunes. I'm pleased with how it turned out.

RF: So if I say Kirk Covington, what do you think of?

AH: The enjoyment I had working with him on this particular project. This was a different project from what either of us do normally, and I would love to have a chance to play with him on my own music. But that's an experience I've yet to have. I would really look forward to playing with him in a context that is outside the one we just did.

RF: Speaking generally now, what would you not care for from a drummer?

AH: Overstating beats. Some people turn around and go, "But he doesn't groove." To me, they're listening all wrong, because nobody grooves harder than somebody like Gary Husband or anybody we've talked about. Gary grooves, it's just that the groove is not overstated. When people say that something is really grooving, I generally don't like it because that means it's static. I like drummers who play in waves...flowing. A lot of instrumentalists like the drums to play straight so that they can play over them. If the drummer is playing too much, they'll stop him: "This is the guitar solo, just play the groove." I hate that with a passion. I like the drummer to be part of the soloing; he's part of what's going on. I like a player who's like a drummer and percussionist combined in one, instead of just having the drummer play the beat while the percussionist plays. I feel that all the drummers I've played with have brought something really unique and beautiful to the music. They've made my music sound better because of the way they've performed it.

RF: You said you like the drums to integrate into the music totally instead of laying out on a solo. Do you want the cymbals to sound a certain way as well?

AH: I'm not a big cymbal fan. If you threw the cymbals away, I'd be quite happy. They're like generated white noise as far as I'm concerned. They mask a lot of other frequencies and they get in the way. But not everybody plays them the same way. Gary and Chad play the cymbals very differently, for example. Both drummers are very powerful, but Gary's cymbals are much more predominant than Chad's, just in the way he plays.

RF: And that's okay with you?

AH: It's fine. It's just the way it is.

RF: But would you prefer it if he threw his cymbals out?

AH: [laughs] I wouldn't really. I'd prefer it if they got a bit smaller, perhaps. He's going to hate me for this. Cymbals can get to a point where they're not musical anymore. To me, some cymbals—and the way they're played—are very musical. They're sweet, and the way the time flows is great. But when I start to flinch, well... I don't like when music makes me flinch. I can do without that.

RF: Do you have a preference in sizes of drums?

AH: I tend to like real small kits, but it's different for different drummers because of the way they play. You can't really give everybody the kit of your dreams. Gary Husband has been my longest-standing relationship with a musician, and he's always played the music the closest to the way I hear it in my head. Ironically, when I first met Gary, he had a really small kit. Then I said, "Hey, man, you'd sound really great if you got lots of drums." So he did—and then he found it hard to put them away. So it was my fault! However, we did a tour in England a little while ago where he played a real small kit, and I loved it. I thought he sounded absolutely spectacular on it because he's not the kind of guy who needs a lot of drums: He's a very creative musician, and small drums seem to articulate such creativity. You can hear everything; nothing gets in the way of anything else. Also, usually when there's a smaller kit involved, the cymbals tend to be reduced from bicycle wheels to a reasonable size. I tease Gary about that. We had a cab driver in England one time who got out to put the cymbals in the back, and even he said, "Geez, look at the size of those."

RF: Do you have a bass drum preference?

AH: Again, it's all down to the player. I would never dream of saying, "Do this or do that."

RF: But in your perfect world....

AH: I like little bass drums—20".

RF: Some MD readers may not be too familiar with your music, but they're sure to know all the drummers we've discussed. Are there any particular recordings of yours that you would recommend for the drumming they contain?

AH: Hard Hat Area, Wardenclyffe Tower, and Secrets would be the three I would suggest. There is some absolutely stunning drumming on those three. I was very flattered to read an interview with Vinnie where he was asked to name some tracks he enjoyed playing on, and he included "City Nights" from Secrets. That made me happy because I felt like I actually achieved what I wanted to do: Somebody had the freedom to do what he wanted to do and ended up liking it.

It's my pleasure to be associated with the drummers you've had me talk about. All those guys mean a lot to me. They've done a lot, way above the call of duty. All of those guys have done most of the work they've done with me without being paid. I can't remember the last time I paid someone for work on an album. I'm doubly lucky. The only thing I can say in return is: If they want me to do anything, I'll be happy to do it under the same circumstances.