Guitarist's Guitarist (Jazz Times 1989)

Summary: Allan Holdsworth discusses his musical influences, definition of jazz as a genre rooted in improvisation, and his journey as a guitarist. He highlights the impact of his father, a jazz pianist, on his musical upbringing. Holdsworth's love for saxophonist John Coltrane's music is evident in his fluid, horn-like guitar playing. He reflects on his early struggles in the UK music scene and his eventual move to the US. Holdsworth shares his experiences with record labels and the importance of creative freedom in his music. He also discusses his SynthAxe experimentation and his album "Secrets" featuring notable musicians. He emphasizes the satisfaction of achieving musical wholeness in jazz. [This summary was written by ChatGPT in 2023 based on the article text below.]

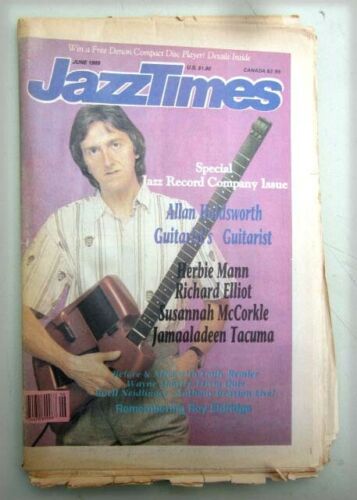

Guitarist's Guitarist

Jazz Times, June 1989

Don Heckman

He's the guitarist most young guitarists place near the top of their list of favorite performers. He's a player whose own, favorite musician is John Coltrane, yet who was recommended for a major label record contract by rock star Eddie van Halen. He's a performer whose still-small, but intensely dedicated fans will go to almost any lengths to hear him play.

A mystery man? Not exactly. His name is Allan Holdsworth, and his gentle , burry accent immediately reveals his near-Scottish roots in the Northern England textile town of Bradford, in Yorkshire. But the truth is that the intensely personal music that he explored in the seventies with such groups as Tempest, the New Tony Williams Life-time and Jean-Luc Ponty, and that earned his EP "Road Games" a Grammy nomination for "Best Rock Instrumental" has yet to break through to the larger audience. This month, his latest recording, Secrets, will be released on the Enigma Records label. Like his most recent two disks, it will feature Holdsworth playing guitar and Synth-Axe (a guitar-like MIDI controller) in a powerfully contemporary brand of improvisational music that Holdsworth, prior identifications to the contrary, is happy to describe as jazz.

"To be honest," he said in a conversation in mid-April. "I call it jazz because the essence of the music is improvisation, and that makes it jazz to me. My dad used to tell me that to him jazz meant improvisation, and it was supposed to be current with what was happening at any particular point in time. Unfortunately some people insist upon tieing jazz to a specific time period. And that's not completely right, I don't think. I always feel that what Charlie Parker did when he came on the scene, or what any other new player does, should be different from what went before. That's what's jazz to me. That's the essence of it,"-

Holdsworth mentions his musician-father frequently. An excellent pianist who spent the World War II years in the Royal Air Force, he was Holdsworth's first teacher. "My father was really a great jazz piano player," he recalled, "and a great influence on my life; He made a living as a musician early on. But after the war, when he got a chance to go to London to play, he changed his mind - decided that he'd been away front home long enough and he wanted to be with my mum. So he just did local gigs.

"In the beginning, he was working as a musician, and then he just made a decision to stop. I guess he played too many dance gigs with drunks leaning over his shoulder. He finally said, I don't want to play this kind of music anymore. To him it was better to get a day job and play the music he wanted to play for his own pleasure. I never understood that at first, but I do, now. I used, to think -that, well, surely any playing's better than no playing. But then, after a" while, you begin to think, well ... maybe not."

Holdsworth's first interest was the saxophone, and its a fascination that has stayed with him right up to the present day. "I loved the sound of it," he said, "and I still do. But we didn't have the money to buy one. When I was about 15, my dad picked up an acoustic guitar from an uncle and just left it laying around. At first, I didn't pay any attention to it. at all. But after it'd been around for a couple of years, I started noodling around on it. When my father saw there was some interest, he started to help me out with chords and stuff. He was such a fantastic natural teacher that he understood the guitar, even though he didn't play the instrument. The funny thing is that he actually wound up teaching it to local students in Bradford.

"The important thing that my dad did was to open me up to all kinds of creative ideas. I was exposed to music from the very beginning, As far back as I can remember I used to play his old albums,- even 78 rpm records, and I heard Charlie Parker and Charlie Christian very early on. And, of course I'd get to hear my dad play on his gigs. When I was about five or six he made me a record player out of one of those mechanical, wind-up turntables. He was into hi-fi, with mono amplifiers, and building stuff."

"He passed away a few years ago. I'm afraid that I never really told him how I felt about him, but I guess that can happen. But I wouldn't be where I am musically now without his influence -that's for sure."

The other significant influence on Holdsworth's playing has been - predictably, perhaps - saxophonist John Coltrane. "When I first started," he explained, "I tried to play pop music - or what was popular at the time, just because it was the only thing that I could manage to play. But I always used to listen to other kinds of music. Then a few years later I started listening to John Coltrane and it was wonderful (in fact, I introduced my father to his music, because he'd never heard it). Shortly after that, Coltrane died. And it was just after I'd fallen in love with his music. I was devastated; I remember locking myself in the toilet for a long time to think about it because I was so moved by what he did."

Even the most cursory hearing of Holdsworth's playing will reveal just how moved he was by Coltrane - the long, fluid lines, the extended improvisations, the phrasing which feels and sounds more like a horn than a plucked string instrument. "It was unconscious in the beginning," Holdsworth said. "But I think I was always trying to make the guitar into a less percussive instrument. That's why I got interested in trying to use the amplifier to create sustained notes - so I could put the instrument into another realm of phrasing. Its not that I like distortion or anything like that for its own sake, its that I liked the way the amplifier could let [me] play long notes. Whereas, the normal jazz guitar - like say Joe Pass - is too percussive for me to be able to relate to it; I still love it and love to listen to it, but it wasn't something that I felt; that's why the SynthAxe was such a great discovery for me. It was like it was suddenly possible for long, flowing lines to be created by a guitar player; and now, with a breath controller, I can control the dynamics using breath like I would if I was playing a horn. So its kind of like a dream come true. Its like I've finally gotten around to playing the saxophone!"

In the two years since he began to play the hybrid instrument, the SynthAxe has loomed larger and larger in Holdsworth's musical arsenal. It now rests comfortably in his hands for at least 50% of most of his live sets.

"Most guitar players don't like the Synth-Axe," he said, "because it feels totally different from the guitar. The strings that you play with the right hand are a separate set from what you play with your left hand. Fret spacing is completely different. So I guess a lot of guys feel totally alienated by it. But I suppose the fact that I really didn't like the guitar allowed me to adapt more easily to the Synth-Axe. I really like it. In fact, I've gotten to a point where I feel as though I cant get as much out of a guitar as I can out of the Synth-Axe.

"I've been trying - and I haven't succeeded yet, but I keep getting closer - to create a kind of a horn sound that's somewhere between an oboe and a soprano saxophone. And since there's no real acoustic instrument that I can learn how to play, I use the synthesizers that I control with the Synth-Axe to create a sound which is somehow like that. I've always liked the idea of synthesis. I mean, there must be so many sounds - unheard sounds - that would be wonderful to hear. The real quest is to find some of them. Hopefully, eventually I'll come up with a sound that isn't trying to be something else, but which is definitely identifiable as something else.

Holdsworth moved to the sates in 1982, after commuting back and forth briefly. It was a move largely driven by desperation, after he found it almost impossible to work in a great Britain obsessed with punk rock.

"I got to the point," he recalled, "where I couldn't make a living in music, and I was on the verge of just getting a job so we could survive. That's normal; it happens to millions of people, and I didn't mind at all. But when I kept seeing my name in American music magazines I thought, 'well, maybe we could do a few gigs over there.' Paul Williams, who was the vocalist in our original hand, lived here in Southern California and said he thought we could line up some work.

Our first was in San Francisco, and the place was jammed. It was like a dream. We went from not being able to get a gig in England to selling out the clubs in the U.S. Then we played the Roxy in Los Angeles, and when we got there in the afternoon there was a line waiting to get in. I couldn't believe it. You have to understand that when we came here, I didn't even have a guitar. I'd sold the last instrument I had to pay for the mix in an album we paid for ourselves. I had a couple of special amps, but that was it, so you can imagine how I felt when we saw people actually waiting to hear us play."

When Eddie Van Halen joined Holdsworth on stage at the Roxy gig and promised to ask Warner Brothers to sign him, it seemed as though the guitarist was well on the way toward a real American success story. But success stories can have a way of getting sidetracked.

"Edward Van Halen was a great guy," said Holdsworth, and he tried to help. That's all he had in mind. He brought a Warner Brothers producer named Ted Templeman to my gig, I started talking with Ted and he said they were interested in doing something, I thought, 'Oh, this is wonderful. Now I'll finally get a chance to do what I really want to do, and get some major label assistance. But in actual fact, it was the absolute 6ppe-site. I think Ted Templeton [sic] didn't really want to sign us at all. I think he was doing it because of Eddie. And also, I think that they really wanted to change my music. They signed me, and then decided they didn't like what I did. I couldn't believe the way the whole album was made - with Ted listening to different vocalists singing over the telephone - with them eventually saying that if I didn't get somebody famous they wouldn't even release the album.

"The whole thing was a real disaster, and the music suffered from it. With the material we had at the time, as well its some of the things that were on the EP, we could have made a much better album than it was. But I couldn't do it the way I wanted to. I had to mix it at Warner Studios with Warner engineers, as opposed to being able to take it where I wanted to take it to get the sound I wanted But that choice was taken away, too.

Despite the success of Road Games, Holdsworth's recording career lurched into a holding pattern, his projected two LP deal circling endlessly with no place to land. "I didn't record for a while after that," he explained. "Warner Brothers couldn't decide what they wanted to do. When. I went in with album ideas, I was met with a lot of opposition because of the problems that they saw in 'Road Games.' Finally, they gave us some money to do a demo of the material that I was proposing for the next album. But when they heard the demo, they refused to let me make another album. It was not exactly a wonderful experience.

His Warner Brothers connection severed, Holdsworth took the demo tracks, finished them into an album which eventually became Metal Fatigue. and was released on Enigma Records. It was followed by Atavachron, on which he introduced the Synthe-Axe [sic] and featured Billy Childs and Tony Williams. When Enigma hesitated with a contract pickup, Holdsworth moved to Relativity for the release of Sand, but his current release is once again back on Enigma.

"The thing that appealed to me about both companies," he said, "is that they didn't tell me what to do. They left me totally alone. Which is amazing, because I did go to a meeting once with a major record company, and I couldn't wait to get out of the office. They said, 'well, basically we see you as a lost individual. We want you to record with these musicians, not those musicians, and play this material with this engineer, with this producer.' And basically they didn't like anything I'd ever done. At that point, I was trying to be polite, but I just wanted to get out of there. I mean, I don't feel lost, at all. Maybe that's how they perceive somebody who wants to do his own music - as a lost individual - but I certainly don't feel that way. I feel like I have a positive direction. Maybe it's one that a major company doesn't feel there's any market for, and I guess they're entitled to feel that way. But it seems sad that they couldn't even appreciate the other musicians because they weren't familiar names . That's really being shortsighted."

With or without large label interest in his career, Holdsworth is moving forward enthusiastically. He is particularly excited about the new album. Secrets, which features L.A. All Star drummer Vinnie Colaiuto [sic] on drums, Jimmy Johnson, his regular bassist, Steve Hunt (a drummer playing keyboards on Maid Marion his own piece), with Chad Wackerman (his regular drummer) also playin on one of the tracks.

"The guys all played incredibly. I was really moved by what they did. Among some of the highlights noted by Holdsworth are drummer Gary' Husband's City Nights (Very nice," says Holdsworth; "with good chord progressions."); Steve Hunt's Maid Marian [sic] ("When he first presented it to us it reminded me of something from Old England, like Robin Hood, but it was quite soft so we renamed it Maid Marian."); Endomorph, a solo piece in which Holdsworth dubs guitar over Synth-Axe; Spokes ("I really liked bicycling riding when I was a kid, and this piece reminded me of it - of wheelies, actually."); 54 Duncan Terrace (This was the address of a really great piano player friend of mine who died a few years ago. He had this wonderful room in his house.. A white room with blue clouds painted on it or maybe it was vice versa And he had this old Bluthner piano in there. The music he used to write was soft and gentle, with colorful harmonics. And I wrote the piece for him. The chord sequen ce sort of reminds me of something he would have done.").

"What pleases me the most about Secrets," he continued, "is that I still was able to hear some kind of progress from the last one. If I don't feel there's any progress being made, I think I'd try doing some other kind of work. If I can hear something that I've learned recently, or if I've recently unlocked some kind of creative door then that makes me happy.

"What I look for in music is wholeness, Holdsworth concluded, "... like when you and the music and the other musicians are all one. That's when everything makes sense. And when that's really working, it makes all the problems and the pain worthwhile. All the guys become like one thing and the music just flies. To me, that's what jazz is really all about."