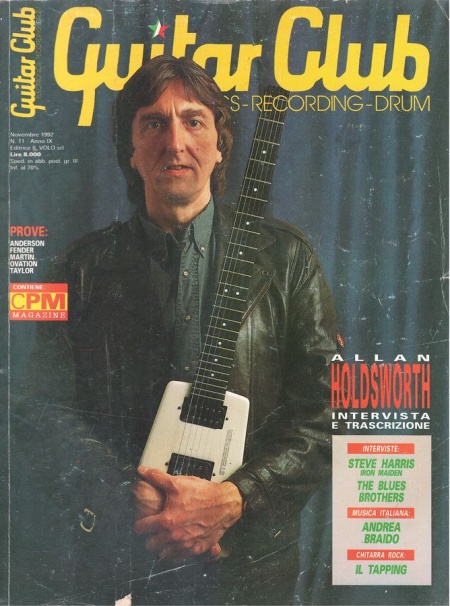

The Guitarist’s Guitarist (Guitar Club 1992)

Allan Holdsworth

The Guitarist’s Guitarist

Guitar Club November 1992

Text by Bill Milkowski

Photo by Roger Balzan

This is a machine translated version of Il chitarrista dei chitarristi (Guitar Club 1992), with some human editing.

Questionable translations are noted in [brackets]. If you would like to improve this translation, please contact Allan Holdsworth Archives on Facebook.

Interview from the States

- He was named the best living solid body guitarist. Dozens and dozens of musicians praise him. Eddie Van Halen said of him: "Holdsworth is the best in my book". Alex Lifeson from Rush said, "Any guitarist who understands something would put him at the top of the list." Larry Coryell called him "a totally revolutionary guitarist", and Neil Schon, speaking of Allan said: "if you play the guitar and think you are too good, try to listen to him".

Yet despite all this praise, fame and fortune at the highest levels have not reached Allan Holdsworth. In fact, it is common knowledge in the musical world that quality and popularity do not always join hands. So, over the last 20 years, through his work with Tempest, Soft Machine, Tony Williams Lifetime, Gong, Jean Luc Ponty, Bill Bruford, the UK and as a solo artist, Holdsworth has remained a cult figure.

Holdsworth grew up in the small textile town of Bradford in Yorkshire, England. He began playing guitar at the age of 17 and although he was initially fascinated by the saxophone, he soon became a fan of guitarist Charlie Christian of the Benny Goodman Orchestra.

Emulating the flow of notes associated with sax, Holdsworth came to present one of the most surprising and unique guitar approaches ever seen in the last twenty years. His long tapered fingers allow him to extend his hand in an incredible way on the keyboard, while powerfully playing those phrasings for which John Coltrane was so well known.

After touring and recording with various important rock instrumental groups, Holdsworth put his own band together in 1980: IOU It has since been released with various albums as the band's leader, the last of which is titled "Warden Clyffe Tower "[sic], on Restless Records label.

We interviewed Allan Holdsworth in New York, at the Bottom Line, after a performance with his new group of four elements: Skuli Sverrisson on bass, Chad Wackerman on drums and Steve Hunt on keyboards.

GUITAR CLUB: One of the problems you have faced over the years is categorization. You're too rock for jazz and too jazz for rock. How did you deal with this particular aspect?

ALLAN HOLDSWORTH: My music is certainly not commercial enough to be broadcast by a rock radio station. And the programmers of the jazz stations are perplexed to hear so many electric guitars. As a result, my music is not broadcast on the radio! In fact, I want my music to be a combination of both, but instead of attracting the two different types of listeners, it seems rather to scare them away from me and leave me in a kind of no man's land. I tried to avoid this by focusing a little more on the listeners of jazz music. A lot of jazz radio stations are now broadcasting music that, in my opinion, is much less jazzy than ours, transmitting funky, very catchy things, which are practically pop songs without lyrics. And for me that music is boring. There is no improvisation, while we improvise in every song every night. And what else is jazz if not improvisation? [Machine back translation]

GC: You used to play a Gibson SG, then you started playing Charvel guitars and later Ibanez. You recently played only Steinberger guitars.

AH: Yes. I found the wood incredibly frustrating. I couldn't find two wooden guitars that have the same identical sound. But the Steinberger guitars are all identical. And there are aspects that I like very much. Since they are not made of wood, the body does not undergo the effects of temperature changes, and they always stay tuned. And the fact that the strings are fixed with the dots [ball ends], rather than the usual excess string on the end is in my opinion a great step forward. The guitar has remained firm on the same concepts for almost 30 years since the creation of the first Fender Stratocaster. In my opinion, Ned Steinberger was the only one to create something new from the time of the Strat onwards. He has an innovative mind and his instruments work. The sound is pure and uniform all along the neck. And under that profile [???] it is a "very controllable machine". The first Ibanez guitar they did for me, the red AH-10, had a fabulous sound. But they were not able to make another that had a sound remotely similar to the original. I have eight or nine other Ibanez guitars at home, and as far as I'm concerned, they are unplayable because, in my opinion, they don't have a good sound. The first Ibanez is still great. [Machine back translation]

GC: How did you discover Steinberger?

AH: I saw one at NAMM and thought "This thing absolutely can't work". I thought the idea sounded ridiculous, but I picked it up, deciding to try it. I played it for ten seconds, and immediately ordered one. I hadn’t felt so excited in front of a guitar from the age of 20. It was a case of love at first "touch"! [Machine back translation]

GC: You recently used a white double neck Steinberger. What do you need the two necks for?

AH: They have two different tunings. One handle has the standard tuning and the other is tuned in fifths (Do, Sol, Re, La, Mi, from bottom to top). I started playing this double neck so that I could continue playing the music I had written on the SynthAxe. When I played the Synth-Axe I went from one tuning to another. [Machine back translation]

GC: What happened to the Synth-Axe? A couple of years ago you swore to do nore more tours with a traditional electric but only with the SynthAxe: yet you didn't use it on this last tour! ...

AH: Right now I have problems with the Synth-Axe because I can't get it fixed. The company is selling all the old ones, but they are not going ahead with the design of the tool. They do not update it and do not incorporate any of the ideas I suggest. So for me it has become like a big dinosaur. I went on tour and broke down right in the middle, so I wasn't able to play anymore because nobody knew how to fix it. I love it as a tool but there is no possibility, with my limited knowledge of electronics, that I can repair it by myself. So I tried to make choices based on its poor reliability, which is why I decided to switch to a Steinberger double neck. [Machine back translation]

GC: Has the Synth-Axe company withdrawn from business?

AH: No, it's still there but it's not developing the tool any further. For years I wanted a shorter neck as I was convinced that this was a design mistake. The neck is so big that it's a problem ... [Machine back translation]

GC: What did you initially like about Synth-Axe?

AH: I liked the idea that it was a synth that didn't use the pitch-to-voltage principle that I think has some intrinsic problems that are really hard to overcome. I tried the Roland guitar synth and I didn't like it because I couldn't play it the way I wanted. And I hate being limited by a car. The Roland guitar synth is a truly disobedient machine. It takes a long time to decide what note you played. Furthermore, the wavelengths of a low note are higher than those of a high note, consequently all the low notes come out much slower than the high ones. It has a whole series of problems of this kind. But the Synth-Axe is a thing in itself. It's a spectacular machine: it doesn't make pitch mistakes. It can't do it! Manipulation and frequency analysis have been eliminated. And an obedient machine. When I first got it I thought it was made for me. I was amazed. I just wish mine would continue to work. [Machine back translation]

GC: In your last Synth-Axe tour you had incorporated a breath controller. How did it work?

AH: I've always been attracted to a breathy sound so I started experimenting with this breath-controller to try to get more of this kind in my music. It is an accessory that has existed for a long time. Stevie Wonder and Peter Frampton used it several years ago together with a device called talking box. It's practically a piece of plastic tube connected to my Midi setup. With the Synth-Axe it works so that the instrument does not produce any sound by itself until I blow through this plastic tube. And the sound changes according to the breath I put in, both in volume and in tone. Peter Frampton's 70s voice box gave shape to the sounds. It made sounds active. All you have to do is blow into your instrument, just like a saxophonist, I suppose. I've always been a potential and frustrated saxophonist. I never wanted to be a guitarist. I became a guitarist because as a young man I was handed a guitar and I started to strum it, then it became a passion. I have always loved music as a boy, but the instrument that I wanted to play at that time was a wind instrument of any kind, whether it was an existing instrument or an instrument from some other unknown planet ... [Machine back translation]

GC: During some of your most intense ones and especially when using the breath-controller, do you reach the levels of inspiration of a John Coltrane?

AH: He has greatly influenced me and continues to inspire me. I listen to his music a lot along with music by Keith Jarrett, Michael Brecker and Pat Metheny. Saxophonists involve me in a special way, but when I listen to horn players I get ideas from their harmonic concepts. Compared to guitarists, they seem to be more open from a harmonic point of view. [Machine back translation]

GC: What other problems did you encounter regarding the design of the Synth-Axe?

AH: I had to get used to the spacing of the keys and the shape of the neck, both totally different from those of a guitar. The space between the keys is almost identical along the entire keyboard. They are slightly closer together in the lower part of the handle near the nut and are a little more distant in the upper part. This caused me some problems at the beginning. I was a little disoriented but got used to it. And because of the different spacing there were some chords that I couldn't play on the Synth-Axe. I didn't get it with my fingers. The chords I used to play regularly on the top two-thirds of a regular guitar suddenly became impossible to play on the Synth-Axe. So I suggested to the company several solutions for the neck, but they never made them. [Machine back translation]

GC: So now that you have more or less placed the Synth-Axe on the shelf, you present yourself with another revolutionary design. Tell us about this strange guitar you recently discovered.

AH: This is a basic Steinberger design, but the person who built it is a luthier named Bill DeLap. It is a baritone guitar. It has a lower range than a normal guitar, a bit like the difference between an oboe and an English horn or between a clarinet and a high clarinet. I have three baritone guitars. Two have a 38 inch long necks, which is about 4 inches more than the neck of a traditional electric bass. The lowest note you can play is an A (“La”). [Machine back translation]

GC: What is the idea behind these baritone guitars?

AH: I wanted to have the lowest notes, but I also wanted the sound that I usually like to have with my guitars. And I didn't want to change the diameter of the strings or anything like that because then the sound would have changed drastically. The only way to do this is to make sure the string length is 25.5 inches by playing an E (“Mi”). Then the rest is obtained from there. This is a rather funny scale. I think the neck is actually longer than the neck of an upright bass. [Machine back translation]

GC: Tell us about your last recording for Restless Records

AH: In fact, it's very frustrating, because we recorded this record in June last year. I started the mixing job, but then I wasn't able to complete it because we left for a tour. When I returned I decided to remix it because there were a couple of things that didn't satisfy me. There was a certain inconsistency on the bass, so I did the mixing again. But before I could finish it, I had to leave again on tour. And here we are, a year later ... and the work was there waiting all this time! Usually when I work on an album, I close the door and focus only on recording and mixing until I finish it. And I don't accept other commitments. But this time many things have hampered my work. It was a situation that should have been done and completed last year but not done. And at this point I'm already tired of this music because I've been listening to it for a year and I have other things I would like to record. I am actually getting ready to record new things, so there is the possibility that I will go out with two different albums in the span of six months: something quite funny considering that I haven't released an album for three years! [Machine back translation]

GC: What is the title of the new album?

AH: "Warden Clyffe Tower", which is the name of an energy transfer tower built by Nicholas Tesla and Warden Clyffe, New Jersey. I think the name is written another way, probably Warden Cliff. But I decided to use Old English spelling because I like it better. [Machine back translation]

GC: Who plays on this new record?

AH: Jimmy Johnson on bass, Gary Husband on drums on some tracks, Chad Wackerman on others, and Vinnie Colaiuta on one track. But now I can't wait to go to the studio and record all the new material with my trio, namely with Chad on drums and Skuli Sverrisson on bass. Skuli is a very good young bass player, from Iceland, whom I met last year. Unfortunately, I met him after having recorded the material for "Warden Clyffe Tower", otherwise I would have had him play for some tune in that album. He's a great bass player. I think he will become a monster. [Machine back translation]

GC: What guitars did you play on the album?

AH: For the most part a regular Steinberger and two different baritone guitars: one goes down to B flat (“Si bemolle”), the other to C (“DO”). [Machine back translation]

GC: What effects are you bringing on tour during this period?

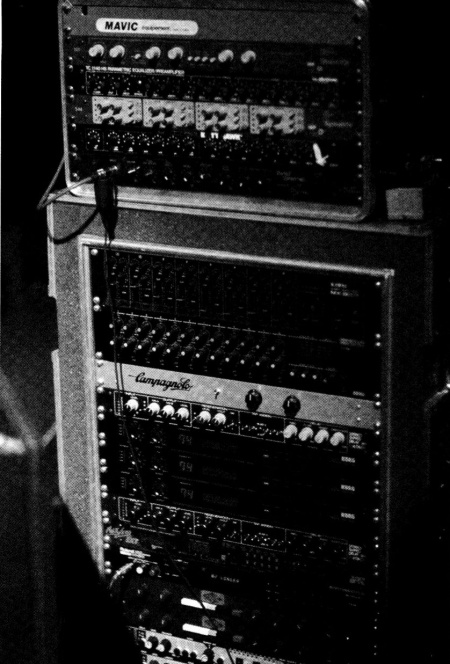

AH: My rack includes an ADA Stereo Tapped Delay as chorus; a TC Electronics Spatial Expander, a Lexicon PCM-41; a Delta Lab DL-4 as echo and delay; an Intellifex, the latest Rocktron processor. I also have an old Yamaha D-1500 digital delay; a Roland digital delay and a Boss SD-200 volume pedal. I use parametric equalizers TC Electronics. I play in stereo using a couple of amps, generally Pearce. I pass everything through a Kawai mixing console and a pair of 12-inch JBL monitors. [Machine back translation]

GC: Can you describe your concept for solos in principle?

AH: I tend to feel the flow of notes that form a whole rather than one note after another. This from the beginning to the end. [Machine back translation]

GC: In addition to experimenting with sound, you have also pushed yourself beyond the limits of the guitar technique by using strange fingerings and very long extensions of the hand on the fretboard.

AH: One of the things I discovered very soon was that if I played as many notes as possible on a string, I reached the kind of sustain I was looking for. So I started doing exercises playing scales for hours and hours, every day, playing four notes on each string until the sound ran as I heard it [???]. And this opened my eyes to a new approach to the guitar. [Machine back translation]

GC: Did anyone influence you or did a teacher help you in this direction?

AH: No. My only teacher was my father, Sam Holdsworth. He was a great pianist and always helped me with the chords and the scales. But since he wasn't a guitarist, he couldn't tell me how to perform on the guitar. And I think this was the reason why I developed a technique so unorthodox. I learned things from the piano and found my own way of transposing those things on the guitar. And I've always tried to apply logic to everything I did. I watched the guitarists better than me at that time and noticed that they used only two or three fingers of the left hand. And it seemed to me an immense waste of energy. I realized that I had to use all the fingers I had available. And it was at that moment that I began to practice extremely meticulously with all my fingers, making sure that no finger worked less. I acquired great dexterity through constant repetition and constant exercise. I didn't know it had to be done that way, it just seemed logical to me. [Machine back translation]

GC: Can you evaluate your playing over the years? Do you see an improvement?

AH: I see an improvement regarding my playing, I can't deny it. But there are always problems to solve with the instrument. You can get over a mountain and there is another one right away. It is a constant struggle. Sometimes it gets a little frustrating. [Machine back translation]

GC: You are very flattered by the young guitarists who buy your records and come in large numbers to your shows. How do you take the fact of having been named a "God of the Guitar"?

AH: It's a flattery in many ways, but in other ways I don't like it because it makes me feel too uncomfortable playing in front of an audience of guitarists only. I want to reach normal people, not just guitarists. I would rather have my music broadcast on the radio and be heard by a larger audience than the mere sphere of guitarists. Obviously a lot of people might not like my music, but some might like it if they had the opportunity to hear it. If you have never tasted an orange, you cannot know if you will like it or not. And that's what I want to do now. I want to reach a new audience and communicate with people who are not necessarily musicians. I think there's something in my music that they like. Whether they understand it or not doesn't matter, as long as you like it. But reaching these people requires a great promotional boost from the record company, something I have never received before. So we'll see what happens with this new record. Perhaps the Restless will push it ... [Machine back translation]

GC: What other projects do you have?

AH: Like I said. I would like to record this new material with Chad and Skull. Then I'll make an album of pure jazz standards with acoustic bass, piano and drums. We will simply go to the studio. We will play some songs, and we will see what I will succeed in hunger [e vedremo cosa riuscirò a fame]. My friends have been asking me for a standard album for years. They think that if I start playing old familiar tunes, it could help people understand what I do. It could be true. [Machine back translation]

GC: Who do you plan to work with for this standard project?

AH: I'm not sure about bass and drums, but I'll definitely work with pianist Gordon Beck. We've worked together before, and he's very familiar with the jazz standard repertoire. He sent me a lot of things and now we just have to choose eight or nine songs, go to the studio and play them. I imagine that the whole session will take no more than a couple of days for the recording. [Machine back translation]

GC: We have heard that you intended to open your own brewery in America.

AH: It is something I meditate on whenever I get frustrated with music. But I usually get down because of the commercial aspect of the music and not because of the music itself. I don't want to stop playing the guitar, but I don't want to play to live. Go to the same places where you played in the last ten years and have to come to terms with the apathy of record companies! ... sometimes it's really too stressful! I would have already given up on business if I had known how to do something else. I have to find another way to support a family. Maybe I'll do a bank robbery! ... [Machine back translation]

GC: Move your fingers very fast. Maybe you can find a job as a typist ...

AH: There’s an idea!

ChatGPT version, sept 2023

Allan Holdsworth is a globally renowned guitarist, admired by many of his fellow musicians. Eddie Van Halen, one of the world's most famous guitarists, praised him by saying that, in his book, Holdsworth is the best. Alex Lifeson of Rush also expressed admiration for Holdsworth, placing him at the top of the list of guitarists. Larry Coryell described Holdsworth as a guitarist who revolutionized the way of playing the guitar, while Neil Schon advised anyone who feels too confident in their guitar-playing abilities to listen to Holdsworth to put themselves to the test. Allan Holdsworth is clearly regarded as one of the best guitarists in the world of music.

However, despite all these praises, fame, and fortune, Allan Holdsworth has not reached the highest levels of mainstream recognition. It is a well-known fact in the music world that quality and popularity do not always go hand in hand. Therefore, over the last 20 years, through his work with Tempest, Soft Machine, Tony Williams Lifetime, Gong, Jean-Luc Ponty, Bill Bruford, U.K., and as a solo artist, Holdsworth has remained a cult figure. Holdsworth grew up in the small textile town of Bradford in Yorkshire, England. He started playing the guitar at the age of 17, and although he was initially fascinated by the saxophone, he quickly became a fan of guitarist Charlie Christian from Benny Goodman's Orchestra.

Emulating the typical saxophone-like flow of notes, Holdsworth developed one of the most astonishing and unique guitar approaches seen in the last twenty years. His long, slender fingers allow him to stretch his hand incredibly across the fretboard while simultaneously playing those phrases for which John Coltrane was so famous. After touring and recording with various prominent instrumental rock groups, Holdsworth put together his own band in 1980: I.O.U. Since then, he has released several albums as the band's leader, the latest of which is titled "Warden Clyffe Tower" on the Restless Records label.

We interviewed Allan Holdsworth in New York, at the Bottom Line, after a performance with his new four-piece group: Skuli Sverrisson on bass, Chad Wackerman on drums, and Steve Hunt on keyboards.

GUITAR CLUB: One of the problems you've had to deal with over the years is categorization. You're too rock for jazz and too jazz for rock. How have you addressed this particular aspect?

ALLAN HOLDSWORTH: My music is certainly not commercial enough to be played on a rock radio station. Rock radio programmers are puzzled by hearing so many electric guitars. As a result, my music doesn't get airplay on the radio! In fact, I want my music to be a combination of both things, but instead of attracting both types of listeners, it seems to scare them away and leave me in a kind of no man's land. I've tried to avoid this problem by focusing a bit more on jazz music listeners. Many jazz radio stations are now playing music that, in my opinion, is much less jazzy than ours. They play funky, very catchy stuff, which is practically instrumental pop songs. And to me, that music is boring. There's no improvisation, whereas we improvise in every song every night. And what else is jazz if not improvisation?

G.C.: First, you used to play a Gibson SG, then you switched to Charvel guitars, and later on, Ibanez. Recently, you've been playing exclusively with Steinberger guitars.

A.H.: Yes, I found wood incredibly frustrating. I couldn't find two wooden guitars that had the exact same sound. But Steinberger guitars are all identical. There are aspects I really like about them. Since they're not made of wood, the body isn't affected by temperature changes, and they always stay in tune. Also, the idea of locking the strings with the ball ends, rather than having excess string hanging at one end or the other, is a big step forward in my opinion. The guitar has remained stuck with the same concepts for almost 30 years since the creation of the first Fender Stratocaster. I think Ned Steinberger was the only one to create something new from the time of the Strat onwards. He has an innovative mind, and his instruments work. The sound is pure and consistent all along the neck. So, it's a very "controllable machine" in that regard. The first Ibanez guitar they made for me, the red AH-10, had a fabulous sound. But they couldn't make another one that came close to the original. I have eight or nine other Ibanez guitars at home, and as far as I'm concerned, they're unplayable because, in my opinion, they don't sound good. The first Ibanez, however, is still great.

G.C.: How did you discover the Steinberger?

A.H.: I saw one at NAMM, and I thought, "This thing absolutely can't work." I thought I'd look ridiculous, but I picked it up and decided to try it. I played it for ten seconds and immediately ordered one. I hadn't been this excited about a guitar since I was 20. It was a case of love at first "touch"!

G.C.: Lately, you've been using a white double-neck Steinberger. What do you use the two necks for?

A.H.: They have two different tunings. One neck has the standard tuning, and the other is tuned in fifths (C, G, D, A, E, from low to high). I started playing this double neck so that I could continue to play the music I had written on the SynthAxe. When I played the SynthAxe, I would switch between tunings.

G.C.: What happened to the SynthAxe? A couple of years ago, you swore off touring with a traditional electric and said you would only tour with the SynthAxe, but you haven't used it on your recent tour!...

A.H.: Right now, I'm having issues with the Synth-Axe because I can't get it repaired. The company is selling off all the old ones but not moving forward with the instrument's design. They're not updating it and not incorporating any of the ideas I suggested. So, for me, it's become like a big dinosaur. I would go on tour, and it would break right in the middle, so I couldn't play anymore because no one knew how to repair it. I love it as an instrument, but there's no way, with my very limited knowledge of electronics, that I can repair it myself. So I tried to make choices based on its unreliability, which is why I decided to switch to a Steinberger double neck.

G.C.: Did the Synth-Axe company go out of business?

A.H.: No, they're still around, but they're not further developing the instrument. For years, I wished for a smaller neck because I thought that was a design flaw. The neck is so thick that it's a problem...

G.C.: What initially appealed to you about the Synth-Axe?

A.H.: I liked the idea that it was a synth that didn't rely on the pitch-to-voltage principle, which I think has inherent problems that are hard to overcome. I tried the Roland guitar synth, and I didn't like it because I couldn't play the way I wanted to. And I hate being limited by a machine. The Roland guitar synth is a really disobedient machine. It takes a long time to decide what note you've played. Also, the wavelengths of a low note are longer than those of a high note, so all the low notes come out much slower than the high ones. It has all sorts of problems like that. But the Synth-Axe is in a league of its own. It's a spectacular machine: it doesn't make pitch errors. It can't make them! Manipulation and frequency analysis are eliminated. It's an obedient machine. When I first got it, I felt like it was made for me. I was amazed by it. I just wish mine would keep working.

G.C.: On your last tour with the Synth-Axe, you had incorporated a breath controller. How did that work?

A.H.: I've always been drawn to a breathy sound, so I started experimenting with this breath controller to try to incorporate more of that quality into my music. It's an accessory that has been around for a long time. Stevie Wonder and Peter Frampton used it many years ago along with a device called a talk box. It's essentially a piece of plastic tubing connected to my MIDI setup. With the Synth-Axe, it works so that the instrument doesn't produce any sound on its own until I blow through this plastic tube. And the sound changes depending on how much breath I put into it, both in volume and tone. Peter Frampton's voice box from the 1970s shaped the sounds. It made the sounds active. All you had to do was blow into your instrument, just like a saxophonist, I suppose. I've always been a potential and frustrated saxophonist. I never wanted to become a guitarist. I became a guitarist because I was handed a guitar when I was young and started plucking it, and it became a passion. I always loved music as a kid, but the instrument I wanted to play at that time was any kind of wind instrument, whether it was an existing one or an instrument from some unknown alien planet...

G.C.: During some of your more intense solos, especially when you use the breath controller, do you reach the levels of inspiration of a John Coltrane?

A.H.: He has greatly influenced me and continues to inspire me. I listen to his music a lot along with the music of Keith Jarrett, Michael Brecker, and Pat Metheny. Saxophonists particularly engage me, but when I listen to horn players, I get ideas from their harmonic concepts. They seem to be more open harmonically compared to guitarists.

G.C.: What other issues have you encountered regarding the design of the Synth-Axe?

A.H.: I had to get used to the key spacing and the shape of the neck, both of which are completely different from a guitar. The spacing between the keys is almost identical across the entire keyboard. They are slightly closer together in the lower part of the neck near the nut and a bit farther apart in the upper part. This initially caused me some problems. I was a bit disoriented, but I got used to it. Due to the different spacing, there were some chords I couldn't play on the Synth-Axe. I couldn't reach them with my fingers. Chords that I typically played on the top two-thirds of a regular guitar suddenly became impossible to play on the Synth-Axe. So, I suggested various neck solutions to the company, but they never implemented them.

G.C.: So, now that you've more or less put the Synth-Axe on the shelf, you've come up with another revolutionary design. Tell us about this strange guitar you recently discovered.

A.H.: It's a basic Steinberger design, but it was built by a luthier named Bill DeLap. It's a baritone guitar. It has a lower range compared to a regular guitar, somewhat like the difference between an oboe and an English horn or between a clarinet and a bass clarinet. I have three baritone guitars. Two of them have a neck that's 38 inches long, which is about 4 inches longer than the neck of a traditional electric bass. The lowest note you can play on them is an A.

G.C.: What's the idea behind these baritone guitars?

A.H.: I wanted to have lower notes, but I also wanted the sound I usually like to have with my guitars. And I didn't want to change the string diameter or anything like that because that would drastically change the sound. The only way to do it is to make sure the string length is 25.5 inches when playing an E. Then you derive the rest from there. It's a rather peculiar scale. I think the neck is actually longer than the neck of an upright bass.

G.C.: Tell us about your latest recording for Restless Records.

A.H.: It's actually very frustrating because we recorded this album in June of last year. I started the mixing work, but then I couldn't finish it because we went on tour. When I came back, I decided to remix it because there were a couple of things that didn't satisfy me. There was some inconsistency in the bass, so I redid the mix. But before I could finish it, I had to go on tour again. And here we are, a year later... and the work has been waiting all this time! Usually, when I work on an album, I close the door and focus only on recording and mixing until I finish it. And I don't accept other commitments. But this time, many things got in the way of the work. It was a situation that should have been done and completed last year but wasn't. At this point, I'm already tired of this music because I've been listening to it for a year, and I have other things I'd like to record. I'm actually gearing up to record new stuff, so there's a possibility that I'll release two different albums within a six-month timeframe, which is quite funny considering I haven't released anything for three years!

G.C.: What's the title of the new album?

A.H.: "Warden Clyffe Tower," which is the name of an energy transmission tower built by Nikola Tesla and Wardenclyffe, in New Jersey. I think the name is spelled differently, probably Wardenclyffe. But I decided to use the Old English spelling because I like it better.

G.C.: Who plays on this new record?

A.H.: Jimmy Johnson on bass, Gary Husband on drums for some tracks, Chad Wackerman on others, and Vinnie Colaiuta on one track only. But now I can't wait to get into the studio and record all the new material with my trio, which includes Chad on drums and Skuli Sverrisson on bass. Skuli is a very talented young bassist from Iceland whom I met last year. Unfortunately, I met him after recording the material for "Warden Clyffe Tower," or I would have had him play on a few tracks on that album. He's a great bassist. I think he'll become a monster.

G.C.: What guitars did you play on the album?

A.H.: Mostly a regular Steinberger and two different baritone guitars: one goes down to low Bb, and the other goes down to low C.

G.C.: What effects are you taking on tour with you these days?

A.H.: My rack includes an ADA Stereo Tapped Delay for chorus; a T.C. Electronics Spatial Expander, a Lexicon PCM-41; a Delta Lab DL-4 for echo and delay; an Intellifex, the latest processor from Rocktron. I also have an old Yamaha D-1500 digital delay; a Roland digital delay and a Boss SD-200 volume pedal. I use T.C. Electronics parametric equalizers. I play in stereo using a pair of amps, usually Pearce. I run everything through a Kawai mixing console and a pair of 12-inch JBL monitors.

G.C.: Can you outline your concept for solos?

A.H.: I tend to hear the flow of the notes as forming a whole rather than hearing one note after another. This, from beginning to end.

G.C.: Besides experimenting with sound, you've also pushed the boundaries of guitar technique by using unusual fingerings and extremely wide hand stretches on the fretboard.

A.H.: One of the things I discovered very early on was that if I played as many notes as possible on one string, I achieved the kind of sustain I was looking for. So I started doing exercises playing scales for hours and hours, every day, playing four notes on each string until the sound flowed the way I felt it. And this opened my eyes to a new approach to the guitar.

G.C.: Did anyone influence you or did a teacher help you in these directions?

A.H.: No, my only teacher was my father, Sam Holdsworth. He was a great pianist and always helped me with chords and scales. But since he wasn't a guitarist, he couldn't tell me how to play them on the guitar. I think that's why I developed such an unorthodox technique. I learned things from the piano and found my own personal way to transpose those things to the guitar. And I always tried to apply logic to everything I did. I watched the better guitarists of my time and noticed that they used only two or three fingers on their left hand. It seemed like a huge waste of energy to me. I realized that I had to use all the fingers I had available. That's when I started practicing extremely meticulously with all my fingers, making sure that no finger worked less. I gained great dexterity through constant repetition and exercise. I didn't know it had to be done that way; it just seemed logical to me.

G.C.: Can you assess your playing over the years? Do you see improvement?

A.H.: I see improvement in my playing, I can't deny that. But there are always problems to solve with the instrument. You overcome one mountain, and there's another one right away. It's a constant struggle. Sometimes it can be a bit frustrating.

G.C.: You are highly admired by young guitarists who buy your records and attend your shows in large numbers. How do you feel about being called a "Guitar God"?

A.H.: It's flattering in many ways, but in other ways, I don't like it because it makes me uncomfortable to play in front of an audience of only guitarists. I want to reach regular people, not just guitarists. I would rather have my music played on the radio and listened to by a wider audience than just the guitar sphere. Of course, many people may not appreciate my music, but someone might like it if they had the opportunity to hear it. If you've never tasted an orange, you can't know if you'll like it or not. And that's what I want to do now. I want to reach a new audience and communicate with people who are not necessarily musicians. I think there's something in my music that they might like. Whether they understand it or not doesn't matter, as long as they like it. But reaching these people requires a big promotional push from the record company, which I haven't received so far. So we'll see what happens with this new album. Maybe Restless will promote it...

G.C.: What other projects do you have in mind?

A.H.: As I mentioned, I want to record this new material with Chad and Skuli. Then, I'll make an album of pure jazz standards with acoustic bass, piano, and drums. We'll just go into the studio, play some tunes, and see what I come up with. My friends have been asking me for years to do an album of standards. They think that if I start playing familiar old tunes, it might help people understand what I do. It could be true.

G.C.: Who do you plan to work with for this standard project?

A.H.: I'm not sure about the bass and drums, but I will definitely work with pianist Gordon Beck. We've worked together before, and he has a great familiarity with the jazz standard repertoire. He's sent me a lot of stuff, and now we just need to choose eight or nine tunes, go into the studio, and play them. I imagine the whole session won't take more than a couple of days to record.

G.C.: We heard that you were planning to open your own brewery in America.

A.H.: It's something I contemplate whenever I get frustrated with music. But I usually get down about the commercial aspect of music, not music itself. I don't want to stop playing the guitar, but I don't want to play for a living. Going to the same places where you've played for the past ten years and dealing with the apathy of record companies!... sometimes it's just too stressful! I would have quit the business already if I knew how to do something else. I have to find another way to support a family. Maybe I'll rob a bank!...

G.C.: You move your fingers very fast. Maybe you can find a job as a typist...

A.H.: That's an idea!