Una Chitarra... Un Mito (Strumenti Musicali 1993, Italian)

English summary:

In a September 1993 interview, Allan discussed his musical journey from saxophonist to guitar virtuoso. He emphasized the importance of creativity in music, shared insights into his guitar preferences, effects, and live setup, and expressed a nuanced view on formal music education, favoring personal discovery over structured learning. [This summary was written by ChatGPT in 2023 based on the article text below.]

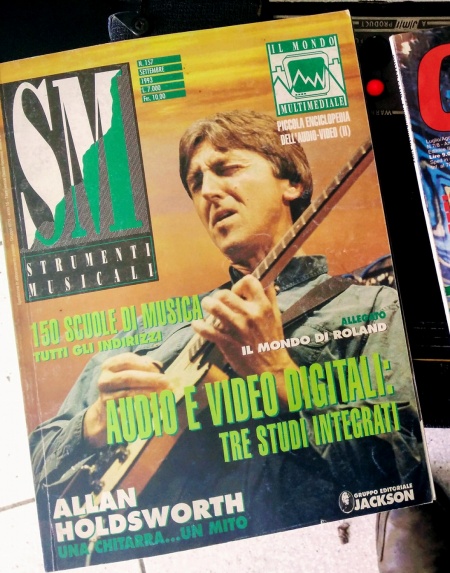

UNA CHITARRA... UN MITO

Strumenti Musical Settembre '93 Roberto Valentino - Foto: Giancarlo Martini

Per molti chitarristi rock e fusion delle ultime generazioni è un vero mito, per tutti è certamente uno degli strumentisti più dotati e innovativi degli ultimi decenni. Eppure la sua prima passione è stata il sassofono e in qualche modo lo si percepisce anche adesso che della chitarra è una star di prima grandezza.

Inglese dello Yorkshire, Allan Holdsworth ha incominciato a interessarsi seriamente allo strumento che gli avrebbe dato così tante soddisfazioni solo verso i 18 anni, un po' tardi forse, in tempo comunque per crearsi quelle solide basi messe in seguito a buon frutto. E in tempo per inserirsi nel vitale movimento del British Jazz anni Settanta: non a caso la sua prima incisione importante la effettuerà con uno dei nomi di maggior spicco di quella corrente musicale, il trombettista lan Carr, all'epoca leader dei Nucleus. La comparsa in Belladonna, anche se in soli due brani, mette infatti in luce Holdsworth che di li a poco entrerà nelle file dei Tempest dell'ex Colosseum John Hiseman, per poi confluire in una delle ultime formazioni dei Soft Machine. Esperienze diverse, in bilico fra jazz elettrico e progressivo rock, che danno il senso della versatilità del musicista, qualità questa che ben si adatta alle esigenze del batterista americano Tony Williams che scrittura Holdsworth per la nuova edizione dei suoi Lifetime. L'avventura americana è fra le più felici ma, come tutte le belle avventure, destinata a finire e, all'indomani dello scioglimento del "New Tony Williams Lifetime", Holdsworth riprende la strada di casa per unirsi ai Gong e per intraprendere un'altra preziosa collaborazione, quella con il violinista francese Jean Luc Ponty. Dello stesso periodo è la costituzione di un supergruppo, gli U.K. - insieme a Eddie Jobson, John Wetton e Bill Bruford - e di li a non molto verrà avviato il fruttuoso sodalizio con il pianista Gordon Beck. Il seguito è storia tutta legata a una carriera solistica improntata a una personale ricerca strumentale che porterà il suo protagonista a cimentarsi anche con un nuovo strumento come il SynthAxe. Questo, in sintesi, l'itinerario musicale di Allan Holdsworth, un musicista che crede fermamente in quello che fa, nella sua musica, nelle possibilità di uno strumento che nelle sue mani sembra sempre proteso verso il futuro. E, al di là del mito, un incontro con lui rivela un uomo e un musicista consapevoli si dei traguardi raggiunti, ma per nulla fermi sulle proprie posizioni. E il nostro, una chiacchierata quasi amichevole più che un incontro professionale, è avvenuto passeggiando per le strade di Ravenna, appe. na concluso il soundcheck per il concerto serale in chiusura dell'edizione '93 di "Mister Jazz", che lo ha visto in scena insieme alla sua attuale band con Steve Hunt alle tastiere, Skuli Sverisson al basso elettrico e l'immancabile Gary Husband alla batteria: un trionfo. C'era da dubitarne?

S.M.: Come è cambiato, se è cambiato, il tuo approccio strumentale dagli inizi della carriera sino a oggi?

Allan Holdsworth: Non penso sia cambiato: si è evoluto attraverso numerose esperienze che mi hanno permesso di apprendere cose nuove, ma è rimasto sostanzialmente lo stesso. È stato un processo di crescita graduale in sintonia con quello che accadeva attorno a me. Tendo sempre od ascoltare il flusso delle note come un tutt'uno, dall'inizio alla fine, piuttosto che ascoltare una nota alla volta. E questo mio modo di vedere si riflette anche nel mio approccio strumentale.

S.M.: Quali sono i chitarristi che ti hanno influenzato maggiormente?

A.H.: Innanzitutto Charlie Christian, poi Django Reinhardt, Jimmy Rainey, Joe Pass...

S.M.: Prima ancora però c'era il sassofono nei tuoi pensieri...

A.H.: Si è vero. Mi piacevano molto soprattutto Cannonball Adderley e John Coltrane: ascoltavo in particolare i dischi in cui tutti e due suonavano con Miles Davis. Erano straordinari!

S.M.: Ascoltavi solo jazz, dunque.

A.H.: Non solo. Ho sempre ascoltato musiche diverse: dal jazz, al pop, alla musica classica.

S.M.: Nel corso della tua attività musicale hai collaborato con molti musicisti, di varie aree espressive, ti piacerebbe rincontrare qualcuno di loro?

A.H.: È sempre bello e stimolante suonare con altri musicisti, ma ciò che mi interessa di più adesso è suonare la mia musica. Per cui, al momento, non vedo il motivo di mettermi a suonare cose di altri: mi piace vera. mente la mine musica e questo mihrere

S.M.: Ma la collaborazione con Gordon Beck continua ancora, però.

A.H.: È una cosa diversa. È una collaborazione alla pari, nessuno di noi due è il leader, suoniamo insieme semplicemente perché ci piace farlo e presto incideremo un nuovo disco composto tutto da standard del jazz.

S.M.: Oltre a questo disco con Gordon Beck, hai in preparazione qualcosa con la tua band?

A.H.: Si, incideremo un nuovo album insie me entro la fine dell'anno. Con i musicisti della mia band mi trovo molto bene, con Gary Husband poi suono da tanti anni e fra noi c'è un'intesa perfetta.

S.M.: Quando si parla di Allan Holdsworth ciò che solitamente viene sottolineato è la tecnica poderosa, il tipico fraseggio legato ecc. Pensi che per un musicista debba essere più importante l'aspetto tecnico o quello creativo?

A.H.: La creatività è sempre la cosa più importante, anche se non sei in possesso di un grande bagaglio tecnico. Uno può anche avere una profonda conoscenza tecnica dello strumento, ma se difetta in fonta sia, in creatività, è difficile che possa portare delle idee interessanti in musica. Comunque si deve sempre creare un equilibrio fra creatività e tecnica, anche se io privilegio il primo aspetto

S.M.: E fra composizione e improvvisazione?

A.H.: Per me improvisare significa suonare ogni volta in modo differente lo stesso brano, significa offrire una visione sempre nuo va della composizione cercando di non ripetersi mai. Questa è la cosa più impor tante: non copiare mai se stessi!

S.M.: Parliamo di chitarre. Con cosa hai cominciato?

A.H.: La mia prima chitarra era una chitarra jazz acustica. Poi mio padre mi compro una Fender Stratocaster che ho usato per alcuni mesi, prima di passare alla Gibson SG che ho suonato per circa dieci anni. In seguito ho adottato diversi modelli, in base a motivazioni espressive, ma anche alle disponibilità economiche del momento. Per un certo periodo ho avuto una Ibanez, modello AH 10, disegnato appositamente per me SM: Adesso cosa usi?

A.H.: Da alcuni anni suono una chitarra Steinberger, che ha modificato per me un lutoio di Monterey, Bill De Lap. E una chitarra baritono che si adatta bene alla mia necessità di avere le note più basse, senza modificare il suono che mi piace ottenere. In sostanza ha solo un range più basso rispetto alle chitarre normali,

S.M.: Da un po' non ti si vede più in giro con il SynthAxe...

A.H.: In effetti e cosi. Mi piaceva molto suonarlo ma da qualche tempo stava diventando pericoloso, nel senso che dimostrava scarsa affidabilità e quando si verificava qualche problema, non ero in grado di ripararlo da solo. Il fatto è che il SynthAxe è uno strumento ancora giovane che abbisogna di un'evoluzione tecnica continua, altrimenti rischia di diventare obsoleto in breve tempo. E io ho bisogno di avere fra le mani uno strumento affidabile che non mi pianti in asso nel bel mezzo di un tour! Allora preferisco suonare solo la chitarra, perché sento sempre il bisogno di andare avanti musicalmente e non mi va di farmi frenare o condizionare da uno strumento che non conosco a fondo.

S.M.: Ti avvali della tecnologia in fase di composizione?

A.H.: No. Ho scritto qualcosa con il Synth Axe, ma generalmente compongo con la chitarra. Le idee compositive nascono in modo diverso: generalmente parto dalla melodia, ma può succedere che l'idea venga da un certo tempo, e a volte è proprio il mio batterista a offrirmi lo spunto.

S.M.: Che tipo di effetti adoperi attualmen te?

A.H.: Quasi sempre uso un delay mono. Non mi piacciono i multiprocessori di segnale perché non c'è ancora quello che ta per me non offrono ancora la possibilità di operare in modo semplice e le cose troppo complesse non le amo molto.

S.M.: Puoi descrivere il tuo rack?

A.H.: Cambio di continuo. Attualmente il mio rack è diviso in due parti: il Clean Rack è composto da due Delta Lab DL 4, che hanno la funzione di eco e di delay, due Lexicon PCM 41, due Roland 3000, due digital delay Yamaha D 1500, un ART Rev. Il tutto entra in un mixer della Kawai. Il Lead Rack è formato invece da tre Korg DRV 3000 e da un mixer sempre della Korg.

S.M.: Quanti amplificatori usi dal vivo?

A.H.: Tre: due per il Clean Rack e uno per il Lead Rack collegato a un Dual Rectifier che mi serve per gli assoli. Sono tutti e tre della Mesa Boogie. Ma come dicevo prima mi piace cambiare, per cui in un prossimo tour avrò quasi sicuramente un rack differente.

S.M.: Ti piace cambiare anche in musica?

A.H.: Mi piace suonare brani dalla struttura diversa, ma la mia direzione musicale penso sia sempre la medesima.

S.M.: Come vedi l'attuale situazione della chitarra nel jazz e nel rock?

A.H.: Nel rock non saprei, perché non seguo questo tipo di musica. Nel jazz ci sono degli ottimi chitarristi, penso a John Scofield, a Scott Henderson, a Frank Gambale. E poi ci sono "grandi vecchi” come Joe Pass, John McLaughlin, Pat Metheny. Sono tutti musicisti fantastici!

S.M.: Un'ultima domanda: pensi che per un giovane musicista sia utile frequentare corsi specifici, come quelli che si tengono in centri didattici famosi come il Berklee o il GIT?

A.H.: Non credo sia necessario o quanto meno indispensabile. Oviamente è la mia opinione personale, ma tante volte i giovani chitarristi frequentano queste scuole pensando di imparare chissà che cosa. La musica è un linguaggio che va scoperto mano a mano seguendo la propria personale sensibilità, il proprio istinto e questo tipo di scuole tendono a spersonalizzare il musicista.

S.M.: Per cui sei assolutamente contrario all'insegnamento?

A.H.: Dico solo che non fa per me. Spero solo di non dover mai insegnare per sopravvivere.

https://web.archive.org/web/20021014134825/http://www.axemagazine.com:80/principale.htm

https://web.archive.org/web/20071121004247/http://www.axemagazine.it:80/index.htm

ChatGPT version, sept 2023

"A GUITAR... A LEGEND September '93 Roberto Valentino - Photo: Giancarlo Martini

For many rock and fusion guitarists of the last few generations, he is a true legend; for everyone, he is certainly one of the most talented and innovative instrumentalists of the last few decades. Yet his first passion was the saxophone, and in some way, you can still perceive it even now, when he is a major guitar star.

Hailing from Yorkshire, Allan Holdsworth began to take a serious interest in the instrument that would bring him so much satisfaction only around the age of 18, perhaps a bit late, but in time to build a solid foundation that would later bear fruit. And in time to become part of the vital British Jazz movement of the 1970s: it's no coincidence that his first significant recording would be with one of the most prominent names in that musical current, the trumpeter Ian Carr, who was leading Nucleus at the time. His appearance in Belladonna, even though in only two tracks, indeed highlights Holdsworth, who would soon join John Hiseman's Tempest, the former Colosseum member, before moving on to one of the later line-ups of Soft Machine. These were diverse experiences, teetering between electric jazz and progressive rock, showcasing the musician's versatility, a quality that suited the needs of American drummer Tony Williams, who recruited Holdsworth for the new edition of his Lifetime band. The American adventure was one of the happiest, but like all good adventures, it was destined to end, and after the dissolution of the "New Tony Williams Lifetime," Holdsworth returned home to join Gong and embark on another valuable collaboration, this time with French violinist Jean Luc Ponty. During the same period, he formed a supergroup, U.K., alongside Eddie Jobson, John Wetton, and Bill Bruford, and shortly afterward, he initiated a fruitful partnership with pianist Gordon Beck. The rest is a story entirely tied to a solo career marked by a personal instrumental exploration that led him to experiment with a new instrument, the SynthAxe. In summary, this is the musical journey of Allan Holdsworth, a musician who firmly believes in what he does, in his music, in the possibilities of an instrument that, in his hands, always seems to be reaching towards the future. And beyond the legend, a meeting with him reveals a man and a musician aware of the milestones achieved but not at all stagnant in their own positions. Our conversation, more like a friendly chat than a professional meeting, took place as we strolled the streets of Ravenna, just after finishing the soundcheck for the evening concert closing the '93 edition of "Mister Jazz," in which he performed with his current band, including Steve Hunt on keyboards, Skuli Sverisson on electric bass, and the ever-present Gary Husband on drums—a triumph. Was there any doubt?

S.M.: How has your instrumental approach changed, if at all, from the beginning of your career to today?

Allan Holdsworth: I don't think it has changed; it has evolved through numerous experiences that allowed me to learn new things, but it has remained essentially the same. It has been a gradual process of growth in tune with what was happening around me. I always tend to listen to the flow of notes as a whole, from start to finish, rather than listening to one note at a time. And this way of seeing things is also reflected in my instrumental approach.

S.M.: Which guitarists have influenced you the most?

A.H.: First and foremost, Charlie Christian, then Django Reinhardt, Jimmy Rainey, Joe Pass...

S.M.: But even before that, the saxophone was on your mind...

A.H.: Yes, that's true. I really liked Cannonball Adderley and John Coltrane, especially listening to the records where both of them played with Miles Davis. They were extraordinary!

S.M.: Did you listen to jazz exclusively, then?

A.H.: Not exclusively. I have always listened to different types of music, from jazz to pop to classical music.

S.M.: Throughout your musical career, you have collaborated with many musicians from various musical backgrounds. Is there anyone you would like to collaborate with again?

A.H.: It's always nice and stimulating to play with other musicians, but what interests me most now is playing my own music. So, at the moment, I don't see any reason to start playing other people's music. I really love my own music, and that's what matters to me.

S.M.: However, your collaboration with Gordon Beck is ongoing.

A.H.: It's different. It's a collaboration on equal terms; neither of us is the leader. We play together simply because we enjoy it, and soon, we will record a new album consisting entirely of jazz standards.

S.M.: Apart from the album with Gordon Beck, do you have anything in the works with your band?

A.H.: Yes, we will record a new album together by the end of the year. I get along very well with the musicians in my band, especially with Gary Husband; we've been playing together for many years, and we have a perfect understanding.

S.M.: When people talk about Allan Holdsworth, they usually emphasize your powerful technique, distinctive phrasing, and so on. Do you think it's more important for a musician to focus on the technical aspect or the creative aspect?

A.H.: Creativity is always the most important thing, even if you don't have a vast technical background. You can have a deep technical knowledge of the instrument, but if you lack creativity, it's difficult to bring interesting ideas to music. However, there must always be a balance between creativity and technique, although I prioritize the former.

S.M.: What about composition and improvisation?

A.H.: For me, improvisation means playing the same piece differently each time, offering a constantly new perspective on the composition and avoiding repetition. That's the most important thing: never copy yourself!

S.M.: Let's talk about guitars. What did you start with?

A.H.: My first guitar was an acoustic jazz guitar. Then my father bought me a Fender Stratocaster, which I used for a few months before switching to the Gibson SG, which I played for about ten years. Later on, I adopted different models based on expressive reasons and also on the economic availability at the time. For a while, I had an Ibanez, the AH 10 model, designed specifically for me.

S.M.: What do you use now?

A.H.: For several years, I have been playing a Steinberger guitar, which has been modified for me by a luthier in Monterey, Bill De Lap. It's a baritone guitar that suits my need for lower notes without altering the sound I like to achieve. Essentially, it only has a lower range compared to regular guitars.

S.M.: We haven't seen you with the SynthAxe for a while...

A.H.: That's true. I really enjoyed playing it, but for some time, it was becoming unreliable, and when problems occurred, I couldn't fix it myself. The thing is, the SynthAxe is still a young instrument that requires continuous technical evolution; otherwise, it risks becoming obsolete quickly. And I need a reliable instrument that won't let me down in the middle of a tour! So, I prefer to stick to playing just the guitar because I always feel the need to move forward musically, and I don't want to be held back or conditioned by an instrument that I don't fully understand.

S.M.: Do you use technology in your composition process?

A.H.: No. I've written some things with the SynthAxe, but generally, I compose with the guitar. Compositional ideas come in different ways: I usually start with a melody, but sometimes the idea comes from a certain rhythm, and sometimes my drummer provides the inspiration.

S.M.: What kind of effects do you use nowadays?

A.H.: I almost always use a mono delay. I don't like signal processors because, for me, they don't yet offer what I need, and they make things too complicated.

S.M.: Can you describe your rack?

A.H.: It changes constantly. Currently, my rack is divided into two parts: the Clean Rack consists of two Delta Lab DL 4 units, which serve as echo and delay, two Lexicon PCM 41 units, two Roland 3000 units, two Yamaha D 1500 digital delays, and an ART Rev. It all goes into a Kawai mixer. The Lead Rack, on the other hand, consists of three Korg DRV 3000 units and a Korg mixer.

S.M.: How many amplifiers do you use live?

A.H.: Three: two for the Clean Rack and one for the Lead Rack, connected to a Dual Rectifier that I use for solos. They are all Mesa Boogie. But, as I mentioned before, I like to change, so in the next tour, I will almost certainly have a different rack.

S.M.: Do you like to change things up in your music too?

A.H.: I like to play pieces with different structures, but I think my musical direction remains the same.

S.M.: How do you see the current situation of the guitar in jazz and rock?

A.H.: I'm not sure about rock because I don't follow that type of music. In jazz, there are excellent guitarists, such as John Scofield, Scott Henderson, Frank Gambale. And then there are the "great old men" like Joe Pass, John McLaughlin, Pat Metheny. They are all fantastic musicians!

S.M.: One last question: do you think it's useful for a young musician to attend specific courses, such as those held at famous educational centers like Berklee or GIT?

A.H.: I don't think it's necessary, or at least not essential. Of course, this is my personal opinion, but many times, young guitarists attend these schools thinking they'll learn something incredible. Music is a language that needs to be discovered gradually by following your own sensitivity and instincts, and these types of schools tend to depersonalize the musician.

S.M.: So, are you absolutely against teaching?

A.H.: I just say it's not for me. I only hope I never have to teach to make a living."