Whisky Galore (Guitarist 2000)

Summary: In an interview, Allan Holdsworth discussed the origins of his unique musical style and his reluctance to create more overtly commercial music. He emphasized his influence from classical and jazz, particularly the revolutionary impact of John Coltrane's playing. Holdsworth also explained his approach to improvisation, striving for seamless blending of legato and picked notes and discussed his gear, including the SynthAxe synthesizer and his quest for a distinctive guitar sound. He mentioned his collaboration with Carvin guitars, Steinbergers, and Yamaha amplifiers. Holdsworth described the ongoing evolution of his playing and the importance of performing for maintaining his skills. [This summary was written by ChatGPT in 2023 based on the article text below.]

Whisky Galore

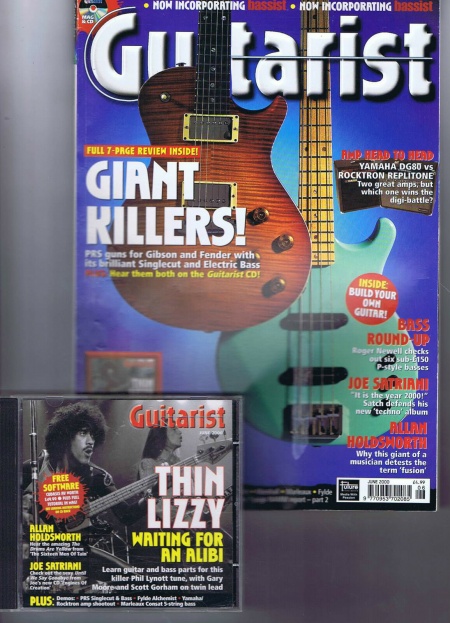

Guitarist, June 2000

Neville Marten

Allan Holdsworth has dedicated his new album to a bottle of single malt whisky. So, one the greatest musicians on the planet is in good spirits then, discovers Neville Marten...

Holdsworth's new album 'The Sixteen Men Of Tain' is an enigmatic collection of compositions that reflect his unique musical viewpoint. Admitting its a kind of 'fusion' of styles which start from a jazz sensibility but can veer anywhere in its travels, Allan concedes that he despises the music that now carries that unfortunate tag. Brought up on a musical diet provided by his father's classical and jazz record collection, Holdsworth realised at an early age that he'd be ploughing a singular path throughout his career and that's proved to be so.

His love affair with the mostly misunderstood SynthAxe lost him a few fans during the '80s and '90s - mainly those who liked him for his deadly fingerboard speed alone - and while his passion for the instrument remains undiminished, he's playing a lot more guitar these days.

Allan, the average listener would be very bemused by your music. Not too many singalong choruses there...

"Not really, no. I don't know where it comes from really; it's like a little portal to the other side. I suppose it was initially classical music, which was what my father played around the house; he had loads of records so there's obviously a lot of classical in there. But he was also a jazz musician and had a lot of jazz in his collection too, so that was another obvious source of information."

Have you ever tried writing anything more overtly commercial?

"No. The biggest lesson I learnt was when I first heard John Coltrane. In the first records with Miles Davis there was Coltrane and Cannonball Adderley and it was the single most revolutionary thing to me. With Cannonball Adderley I could trace the path where it came from, but with Coltrane it was like he'd unplugged the pathway and tapped himself into a direct source. It was just as elevated, but he was coming from somewhere else. It was then I realised you have to elevate your playing, but you don't have to do everything that everybody else did before - again - before you can change something."

Who are the 16 men of Tain?

"That particular track had a particularly festive feel to it and when I think of festivities I always think of alcohol. I've been introduced to the pleasures of single malt whiskies and there's a very famous one in Tain, called Glenmorangie. The 18-year-old Glenmorangie is one of my favourites and on the bottom of every bottle it says, 'Handcrafted by the 16 men of Tain'."

I'm pleased to see there's a lot of guitar soloing on the new record.

"Well the last band album I did was 'Hard Hat Area' and we had Steve Hunt on keyboards and that fills out things sonically. On my solo records I would often play the SynthAxe to fill out some of that missing sound, but I've been consciously trying to lower the SynthAxe content, isolating it to one or two tracks on a record. So yeah, more guitar."

How do you record an album these days? It sounds live but I take it it's not.

"We played everything together. But it used to be that you'd go into the studio and be terrified that you might play something you liked, but somebody else would hate their track so you couldn't use it. So now I just go in there and let what happens happen. Usually I just keep doing it until the other players get it dead right. And if I like what I've played I'll keep it, if not I can do another solo."

You don't fit in with traditional jazzers and yet the music is so harmonically complex that only sophisticated listeners will get it...

"When people mention the word 'jazz' I think of it as music that's harmonic, melodic, rhythmic and a vehicle for improvisation. And that's it: it's not a particular form of music. When you mention jazz to some people they'll think of Acker Bilk and others will say Charlie Parker. Jazz is a very good word, but people have shrunk it by using it in the wrong way. It's like fusion. What I have come to know of fusion is a music that I detest, but there's nothing wrong with the word; it's a perfectly good word."

Do simple chords and music just sound ugly to you, or shallow?

"No, no, not at all. In fact I love some pop music and hate some jazz music - especially the kind of jazz that's everything you've ever heard... again! For example, Bonnie Raitt's I Can't Make You Love Me is beautiful. And the most glorious composition of all time is Debussy's Clare de Lune. I almost can't listen to it without it doing something to me. But it's so simple, but it's like the magic deception."

When you solo, do the notes flow like a stream of unconscious thought?

"Improvisation is the musician drawing from everything he's learned so far The things I'm practising now, it may be a year or two before they're unconsciously coming out in my playing. Obviously you're conscious of the harmony, but it's an unconscious release of all the things you've ever learnt, played over a particular harmonic backdrop. But if your girlfriend runs away with your best buddy and you've got that on your mind when you're on stage, you're probably not going to play your best - unless you're really happy about the event!"

How did you find a bass player that could double those runs on the track The Drums Are Yellow?

"It's not a bass player. It's me with an octavider! I just turned it on and off during the solo. Originally I tried it with a harmoniser, but that was too slow and it just sounded messy, so a friend of mine lent this thing to me. It's no good for playing chords, so any time I wanted to play chords, I'd turn it off."

There's almost no discernable difference between your legato notes and the picked ones. How do you manage to achieve that?

"I've always strived to do that, by playing hammered notes that are louder than ones I've picked. Then you can juggle them about so you really don't know which is which. With some guitarists it's really obvious which notes are picked and which ones are legato, but I like to bury them inside each other so it's more seamless. That's done subconsciously now, so if I want to start a phrase with a really blunt attack, I do it without thinking. I still practise that, to see if I can get it even more extreme."

Tell us about the SynthAxe synth controller. Guitarists never really understood it, did they?

"No they didn't. I suppose some of the things in there are old technology now, but what they achieved with that thing is still amazing. The thing that stood out for me with the SynthAxe was its difference. When I picked it up it was like I'd put on a space helmet and gone to another world. And when I put it down and picked up a guitar, I took the space helmet off and came back down to earth.

"The Axe's problem was guitar players. I remember in California when I was doing some demonstrations for them, I'd be playing it and I'd have the breath controller hooked up and everything. Some guy, inevitably, would come up and say: 'But can you make it sound like a Strat?' and you just want to beat him over the head with it. Then he'd pick it up and go straight to his blues licks!

"When they went out of business I got so depressed. I was using it more than the guitar at one point and I thought, 'You can't do this or you're gonna be trapped; it'll break down and you'll never get it fixed'. So I sold everything and emptied it out of my life. But in six months I was craving it again so I went on a quest to find another one. And I found one, but I never take it out of the studio; it stays at home."

You're one of the few players technically capable of taking really good samples of other instruments and playing them via the SynthAxe....

"But the beauty of the SynthAxe was that it allowed me to go into that other place like in The Lion, The Witch And The Wardrobe. My two favourite synthesisers were Oberheim Xpanders and Matrix 12s, and the old Yamaha DX7. With the Oberheims I was always looking for a haunting, hornlike sound, but one which very obviously wasn't a saxophone, a trumpet or something, which is pointless. The idea was to create a sound that I hadn't heard before."

You had a go at being in a commercial band with Level 42. Is there anyone you'd like to play with these days?

"No, not really. They were really great guys and for the type of music they were doing were really good. But it's the touring side that kills me - not the scheduling, but it's then that you realise what the music really is and that's when it gets to you.

Your guitar tone is huge and thick, almost like a baritone sax...

"Well that's the kind of sound I've been striving to achieve. I'll never get exactly what I want, but it's just like music itself. When I first started listening as a kid, I'd hear some piece of classical music and it would make me want to cry. And I didn't understand it, so instinctively I knew I wanted to be a listener and an absorber of music. It's like when you first fall in love and it's an agony and an ecstasy at the same time; that's because there's something that you don't understand and that's what I love about music. It's like being in love with something you know you're never going to get. And it's the same with the sound: to me the sound is part of the music; I've always strived to achieve a certain sound and that's a neverending quest for me."

How has the Carvin guitar helped in this never-ending quest?

"The first ones were good, but they weren't quite complete for me. But then I designed another one, called the Fat Boy. The top and the back don't touch any wood on the inside, except the edges. So in that respect it's like an acoustic guitar but with no holes. That one turned out really good. You can't put a tremolo on it and that's something I'm really pleased about too. But I'm still really fond of Steinbergers, so that's never going to go away.

And what about your amps?

"For years I've been using Boogies but about two years ago I was in Japan and was introduced the this Japanese guy who designed the digital amp for Yamaha, which became the DC series. And I absolutely loved it. They sent me one to play with for a while and the thing was just amazing. So I have a DG-1000 which is just a preamp; then they came out with the DG-100 which is a 2x12 combo, then the DG-80 which is just a single 12 combo. I've been using the DC-80 combo with a really cool DC-80 extension cabinet. It's still very compact and it's a really cool sound. I basically used those amps on the whole of this record and I was thrilled with it.

A lot of the modelling amps have all these buttons that say 'AC30' or 'Dual Rectifier' and to me that's just a joke. The Yamaha design took some balls because this guy said, 'I'm going to build a digital amplifier but I'm going to decide what it sounds like'.

So he took the whole thing out of that copy-cat mode. With these amps it's very easy for me to get the sounds I like, just by modifying the presets."

How much do you have to play to keep your hands in shape?

"The more I play the better, really. But I could practise all day long, then go to the gig and it's terrible. But you do four or five gigs... it's almost like you need to be in front of an audience for a few days to open up. If I haven't played for a while, I'll get on stage and there'll be a kind of bottleneck and it's usually my hands not being able to do what my brain wants them to. At the other end of the tour there's no bottleneck - there's just no ideas!"