None Too Soon (Guitar Club 1997), English

This is a machine translation with very slight human editing. Original Italian version here: None Too Soon (Guitar Club 1997)

Thank you very much to Gabriele for helping to do the transcription!

== None Too Soon

==

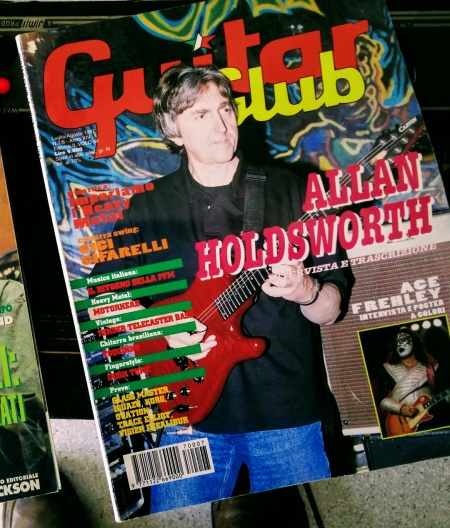

Guitar Club July 1997

By Fausto Forti

GC: Let's start with the last "None Too Soon", including some personal remakes of songs by important authors like Irving Berlin, John Coltrane (Countdown), Django Reinhardt (Nuages), Bill Evans (Very Early), and even Lennon/McCartney (Norwegian Wood)?

AH: With me, in the album he plays an exceptional trio of Gordon Beck on keyboards, Gary Willis on bass and Kirk Covington on drums. The idea of "None Too Soon" came from Gordon. One day he takes me aside and tells me "why do we record a collection of songs known and loved by people, family for most of them? So that they can more easily approach and appreciate what your music is?” [Machine back translated.]

So, if you want, a double purpose: to present songs that belong to our lives, which are now part of us as men and artists, and to be in some way introductory to my way of playing and interpreting music. This is because, speaking of original pieces, those who listen often do not have reference points to better interpret structure and meaning. Especially if the type of approach is not the easiest, the simplest, as in my case. [Machine back translated.]

GC: At that point you chose the authors. Following which criterion?

AH: [xxx] I had a precedent to watch, an album released three years ago, at least I think, for the Japanese market, where guitarists of different musical extractions engaged in a free re-reading of Beatles songs. I think it was called "Come Together". The idea, in its simplicity, seemed immediately brilliant. At that time, Gordon often came to me, we were frequenting each other fairly because they were both engaged in similar projects, and the speech fell on that record. We therefore decided to take advantage of the favorable moment. We therefore called Gary Willis and Kirk (Covington) and began to choose the material. Of course the repertoire to draw on was very vast. We then restricted the field to those authors that we all felt closer, common passions cultivated over time. And so the final playing list came out. Personally, I immediately proposed How Deep is the Ocean by Irvine Berlin for me one of the greatest great composers in the history of music, and Nuages by Diango Reinhardt, another authentic monster of skill and creativity. [Machine back translated.]

Of course, everyone puts the titles on which, in 99% of cases, we immediately agreed. Like Isotope by Joe Henderson or "Countdown" by Coltrane: pillars of our artistic formation. Thinking of Come Together we also focused on a Beatles song, opting for "Norwegian Wood". One of the most particular episodes of the repertano (discovery?), either for the then novelty of the sitar or for the harmonic structure and the melody for once much more important and pre-eminent than words. The remake and result spot on, atmospheric. One of the most profound and touching moments of the collection, perhaps together with Henderson's "Inner Urge." [Machine back translated.]

GC: On the album you almost always use the faithful Steinberger, plus the SynthAxe in two or three tracks. You were a pioneer of synthesized guitar sound. Giving SynthAxe an Aura of Credibility?

AH: Used in three tracks ("Nuages", "None Too Soon" and Very Early), with excellent results. I consider myself neither a pioneer nor a great talent just to be able to produce nice and interesting sounds from this instrument! I never understood the mistrust and indifference that is even worse, towards the SynthAxe. Contrary to what one hears, although its admirers are as numerous as the detractors, this tool is useful and interesting. [Machine back translated.]

Unlike other guitar synths, it does not require specific preparation, it is not necessary to forget your guitar technique and start over. In addition, you can use complete sounds. Mind separated from those of the guitar. I remember that I temporarily left SynthAxe when the company had problems with spare parts. It had become a nightmare: let alone on a tour. Now things have changed. [Machine back translated.]

GC: Was that when you passed in Steinberger?

AH: When I started using the guitar exclusively, I was immediately attracted to the possibilities offered by Steinberger. So (I'm talking about six years ago) I seem to be the most technologically advanced market. Ideal for what has always been the purpose of my being a musician. That is, to bring the guitar and the sounds created by her outside of certain areas, let's say standards, venturing into sound solutions that are absolutely not "characteristic". [Machine back translated.]

GC: At one time you were also using an Ibanez and, alternatively, a Gibson ES-335. As an amplification you have always been faithful to the Mesa Boogie Dual Rectifier.

AH: The Ibanez belongs to the past and so the Gibson, now I play the Carvin model Holdsworth. Regarding the amp you're right, in fact I have always found good with the Mesa Boogie. Speaking of instruments and songs, you must think (remember?) that "None Too Soon", at least its realization in the studio, dates back to almost three years ago. So, for me it is an album now dated. Many things have changed. [Machine back translated.]

GC: Can you tell us something about your next job?

AH: I will play it with the guys I'm on tour with now (Gary Novak and Dave Carpenter), we're a well-matched and well-matched trio. Three different but complementary personalities. At the end of this series of European concerts we will rest for a while and then meet again in the studio in October. The new job should come out early next year. At least I hope. [Machine back translated.]

GC: You were born in Bradford, Yorkshire, on 6 August 1946 and your artistic life is full of important encounters, incidents and recordings. You came into contact in the seventies with the intelligentsia of a certain English Sound, on the border between pop and jazz. which left an indelible mark. I quote John Hiseman at random (before Colosseum then Tempest). lan Carr (author of a wonderful biography of Miles Davis) and Bill Bruford.

AH: Think [remember?] that at the beginning, as a boy, I had no idea or the slightest intention of becoming a musician! In general, on what I wanted to do when I was a big boy, I loved music already, I listened to it in large doses and I enjoyed strumming acoustics: a simple pastime, nothing more different. [Machine back translated.]

From the desire to listen, slowly I switched to that of interpreting, of reproducing those sounds in some way: from the beginning my love was poured on the saxophone: I would have given anything to own one, but unfortunately it was too expensive for my parents' finances, so they bought me a guitar from my uncle, who sold it to Dad. But even then, to become a musician, not even a blurry intention. I started playing with some guys in my neighborhood, I was 18, just to spend a few pleasant hours having fun . Meanwhile I continued to practice and take some lessons from my father, but he was a pianist. I have two brothers and a sister, but I'm the only one with a passion of music. [Machine back translated.]

GC: Do you remember what was your first guitar?

AH: The very first was a cheap sound that I do not even remember the brand, while the first "good guitar" was a Hofner President which cost about 30 pounds. [Machine back translated.]

GC: Then the big jump, to conquer London.

AH: I followed a good saxophonist, who also moved to the capital a few months before, who offered me a room in his apartment. It was 1970. I began to go to the right clubs and met people like John Hiseman and lan Carr. Just with Hiseman, with whom I immediately became a great friend, I began to record. Precisely with Tempest (the new creature after the Colosseum), an album of the same name that I still listen willingly. Although, as long as memory does not play me bad shots, maybe the very first things I did with Ian Carr and his Nucleus. However the period is that. Then the musical situation in London was bubbling, creatively speaking at the top: much better than the current, to understand each other. With lan Carr recorded "Belladonna", not by chance produced by the same Hiseman. So my primary purpose was to gain experience, playing with musicians whom I appreciated and esteemed for me. The atmosphere was of great creative ferment. With Tempest I used a Gibson ES-335 that belonged to Paul Williams, the singer. Then with the Nucleus I went to another Gibson, an SG, and a model built specifically for me by a fellow from London, a particularly gifted craftsman. My first Signature Model! [Machine back translated.]

GC: After passing through the ranks of the Tony Williams Lifetime.

AH: Recorded two records, "Believe It" is "Million Dollar Legs." Playing with him was really the best, a fantastic person, very human and kind, a professional and available artist. Tony was a very good friend. The adventure of Lifetime ends for the simplest of reasons: lack of money. Financially things were getting worse and worse, so the meltdown became inevitable. I used a Gibson SG Custom in those two records. [Machine back translated.]

GC: Another important chapter of your career is the relative to the collaboration with Soft Machine.

AH: I got in touch with them through John Marshall, the drummer, together with Brian Blane, a leading member of the Musicians Union, with whom the Soft Machine collaborated on several occasions. It was a kind of clinics that the band kept from time to time and I was offered to take part in. It was then that they asked me if I wanted to join them, of course I answered yes. We recorded “Bundles”, which remains the only testimony on vinyl because soon I received a phone call from Tony (Williams) and I went with his Lifetime. [Machine back translated.]

GC: Then it was the turn of David Allen's Gong.

AH: I did not know any of them. The meeting took place thanks to the mediation of a manager of Virgin Records who was working then also for the band at a more organizational level. Gong performed for Virgin and he asked me if I was willing to do anything with them. [Machine back translated.]

Note that I had no idea what the music was, that I had never heard them before. A dark jump that turned out to be very interesting. I learned to know and appreciate them, an absolutely unique group. The result was "Gazeuse!". Small detail: I have never met David Allen even today I do not know who he is. Apart from the album, I took part in some studio sessions, which subsequently appeared here and there on a couple of other works. [Machine back translated.]

GC: In a few months, we are around 1976, you passed from Gong to Jean Luc Ponty and then to Bill Bruford.

AH: With the first one I recorded entirely "Enigmatic Ocean" while I was working on some episodes of "Individual Choice" (1983) some years later. Then came Bill Bruford and his solo work "Feels Good to Me" followed by the UK and its record debut. I played with very different people over the years, always feeling at ease, because these and many musical models had a precious common denominator, improvisation. The real hinge around which the music rotates. Jazz is essentially this: learning means constantly creating. [Machine back translated.]

GC: Which music did you listen to as a boy?

AH: I started with jazz, swing, big bands and people like Charlie Christian, Django Reinhardt, Joe Pass and Jim Hall. Then Charlie Parker and John Coltrane and so on. Of course, however, I could not start with jazz, so I adapted to the successes of the moment, pop music undoubtedly easier, more affordable. And then those who came to hear us asked for pop tunes ... [Machine back translated.]

GC: At the beginning of the eighties your solo career began.

AH: The first group that I formed was called False Alarm, as we then changed to IOU (the initials of the phrase, very common in English, "I Owe You", how much I owe you, in cash) because in the early days we paid for we played and spent in transport a lot more than we had in every gig. We were shot in red, a notable passive. The recurring phrase with the organizers was always that "How much I Owe You to play in your club?" I used the faithful SG together with a Fender Stratocaster Custom, made for me by Dick Knight, one of the best British builders. [Machine back translated.]

GC: One of your best works remains "Atavachron". But where does that name come from?

AH: This is an experimental machine used in one of the Star Trek TV episodes. The episode was titled "All Our Yesterdays" and this machine was used to postpone people to their planet. A sort of teleportation. I'm very interested in the science fiction genre. [Machine back translated.]

GC: One last question, the three records you would take away with you ...

AH: Three authors of classical music: the string quartet by Ravel, something by Debussy and Bela Bartok. [Machine back translated.]

[Editorial]

"None Too Soon" is a spectacular collection par excellence: skillful and versatile interventions on famous songs by masters such as Irvine Berlin, John Coltrane, Django Reinhardt and the couple Lennon / McCartney. Along with compositions signed Gordon Beck, keyboardist of enormous talent that accompanies him on this soundtrack alongside nothing less than Gary Willis on bass and Kirk Covington on drums. Obviously, and you will have already understood, we are talking about Allan Holdsworth, the English guitarist who fascinates for his vividly chromatic plans for the almost geometric scans of the interventions and for that minimal sense of the sounds in perennial balance between experimentalism and taste of the back. Conforming himself as a music teacher and consolidating his international reputation, the same that in 35 years of honorable service, brought him in close contact with some of the most brilliant and avant-garde minds of the international music scene from Jon Hiseman to lan Carr, from Jean Luc Ponty to Bill Bruford, through the precious experiences, even brut at the court of absolutely innovative grains such as Soft Machine and Gong. Human and artistic enrichment that are a prelude to the great leap, to the baptism of a solo career still today full of creative ferment. The popularity that made him become a very high profile author in the middle of the 70s when he gave the noble participation in the Tempest album and "Belladonna" signed by lan Carr & the Nucleus, Allan finds himself at the court of Tony Williams and his Lifetime then, in quick succession, appear on the furrows of "Bundles."

One of the most controversial and at the same time rich chapters Musical narratives of the Soft Machine, of "Gazeuse" of the Gong, under the patronage of the mind continuous boiling of David Allen and of "Feel Good" ([sic] by Bill Bruford whose lineup sees Dave Stewart on keyboards, Jeff Berlin on bass and Annette Peacock on vocals. The proof of Allan is superb, capitalized to the point that Bruford wants him with him when, l The following year, he gives life to the UK, a real supergroup, defined by the "art rock band" media, a stellar quartet which includes, in addition to Bill and Allan, John Wetton (King Crimson, Uriah Heep and Roxy Music) and Eddie Jobson (Roxy Music), which i I immediately welcome the unconditional favor of young enthusiasts. The focal points, the centers of attraction, however, remain the compact and jazzy drumming of Bill, who, incidentally, has turned from progressive rock to an American-style fusion jazz, together with the fluid and shiny sound of Allan's guitar: already projected into the future, already with the mind and fingers elsewhere. After a series of varied musical excursions, Bill will arrive at the safe harbor of Robert Fripp while Allan will focus on more marked and experimental jazz fusion.

The eighties opened for Holdsworth in the best way, with its own group called IOU (with Paul Paul Carmichael on bass, Gary Husband on drums and Paul Williams on vocals) and a self-titled album that surprises for the freshness and originality of the songs in the lineup. Since then fifteen years and eight albums have elapsed, among which we deserve the mention "Metal Fatigue" is "Atavachron": quintessence of our masterly guitar technique, so much so as to be still today taken for example by a couple of generations aspiring axemen Yes, because the influence of Holdsworth on his daughters grandchildren, for needs of registry, is really huge .. ask Eddie Van Halen, who nurtures a genuine veneration for him, or to Eric Johnson who never fails to count him among the his greatest inspirations, however, a great deal of fame and due glory corresponds to a closed, introverted character, a shyness that risks being mistaken for grumpiness, impatience, especially with those who have superficial and sporadic relationships. that is, that initial rock, Mr. Holdsworth looks like it actually is - an affable and helpful person, who does not give up a good mug of beer while drawing on The album of memories. The trio he introduces to on this Italian tour includes Dave Carpenter on bass and Gary Novak on drums, and it's a really good feeling. The sound of Allan's Carvin is, if possible, even lighter and more insinuating than in the past, while arpeggios and legato appear more unusual and inspired.

About Carvin (the Los Angeles-based company founded in 1946 by the guitarist of Hawaiian guitar, Lowel Kiesel, who chose the acronym of his sons Carson and Gavin as his name), Allan has contributed decisively to the realization of the model that brings the his name, presented during the last NAMM Show: the result of two years of work, a virtually unique instrument. But he must also be credited with having brought the much mistreated SynthAxe from many illustrious colleagues to the honors of the chronicles called a hybrid, a cross between keyboard and guitar: difficult to use, not very versatile and even less musically expressive. Then he switched to Steinberger, guitar that will become his precious ally (along with a couple of models built specifically by the brilliant Canadian technical Bill DeLapp directly inspired by that of the American house), Starting from the assumption that Allan has increasingly focused on the instrument and its relative improvements rather than taking care of the commercial-financial aspect of his career, he must be recognized as a unique result: that is to have bridged two worlds, that of artificial and synthesized sounds and the other more human and "naturally correct" of the guitar in its traditional meaning of the term, in antithesis by definition. But it is not enough. Allan loves classical music and is very skeptical about the clinics because, in his view, they often end up being just a showcase, an essay of skill. But he has remained perhaps the last pure in a world, that of music, more and more careful to follow fashions, to ride the ephemeral tiger: faithful to the old saying of Uncle Frank (Zappa) "We're only in it for the money "...